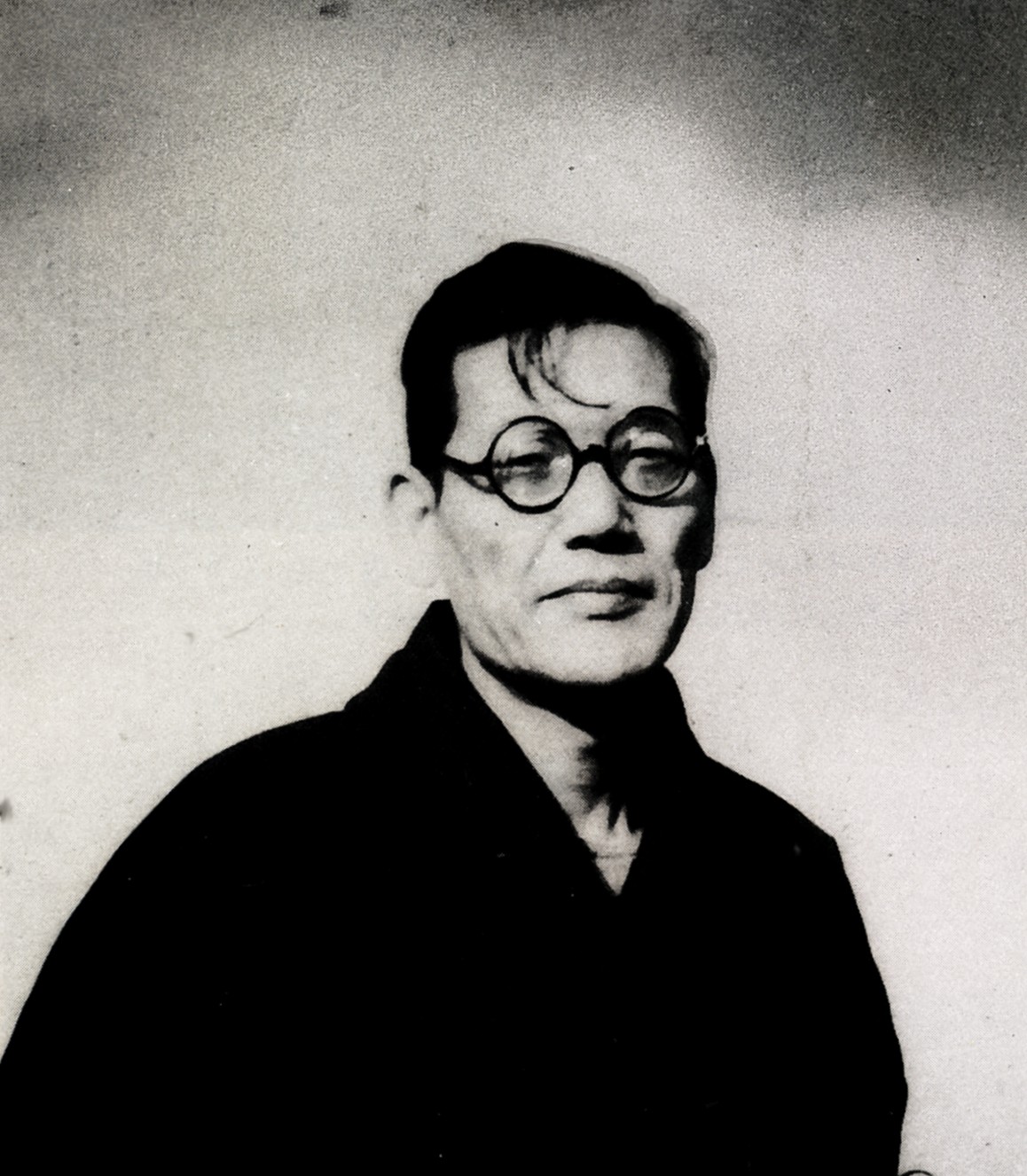

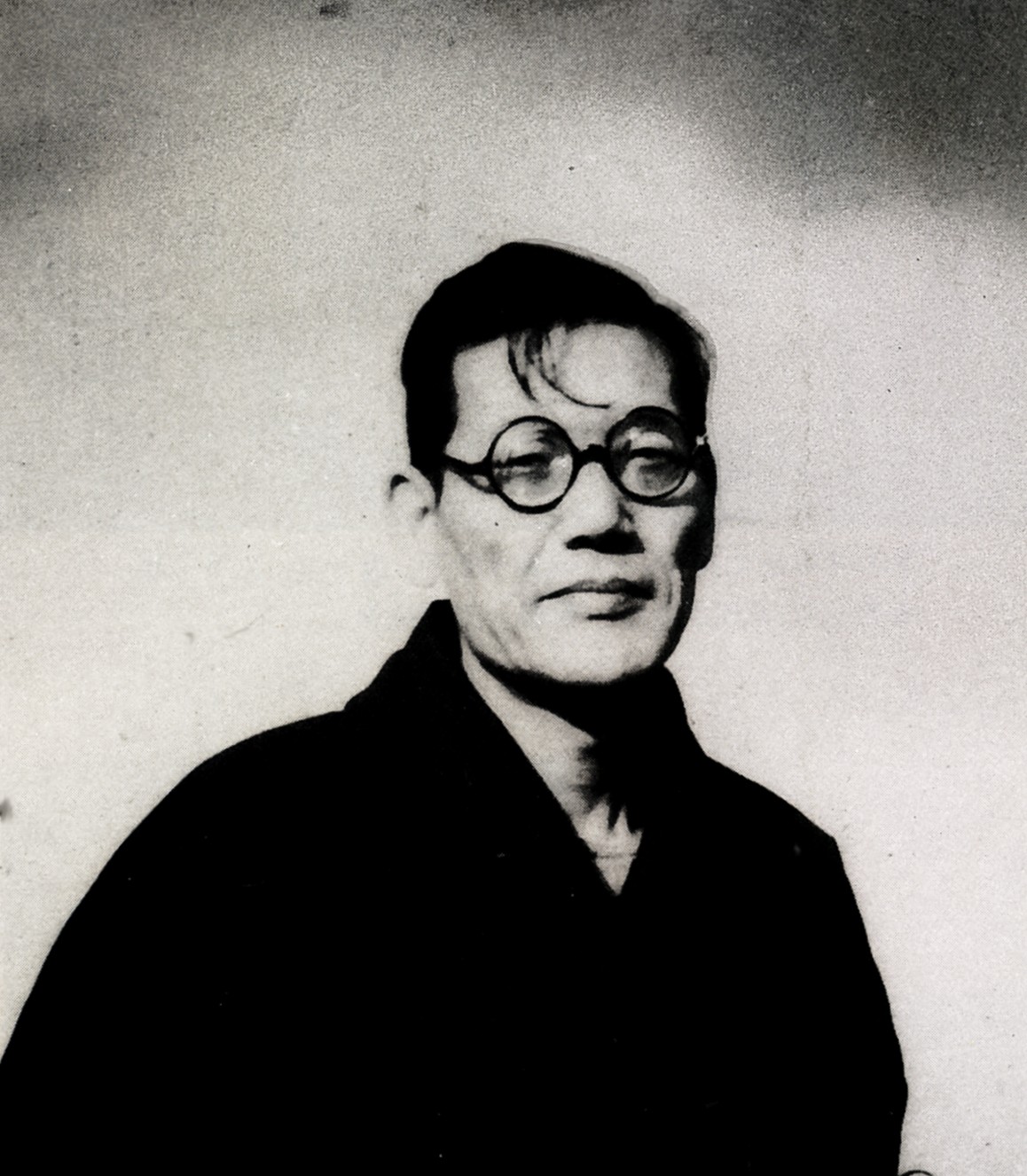

Mita Sekisuke (Amakasu)

First Published: July 1974 issue of Keizai

Source: Mita Sekisuke chosaku-shū (Selected Works of Sekisuke Mita) vol. 4 (1977)

Translated: for marxists.org by Michael Schauerte;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2006.

The following is a transcript from a public lecture in 1974 sponsored by Keizai, a journal of political economy affiliated with the Japanese Communist Party. More than a decade earlier, in 1963, a book by Mita on the same topic had been published, also entitled Shihon-ron no hōhō-ron (The Method of Capital).

Here I am going to discuss the method of Capital. I don't often have the chance to come to Tokyo, and I am happy to be afforded this opportunity to meet so many of you here today, discuss my recent views on this topic, and then hear your questions and comments.

Capital, needless to say, is a work that clarifies the essence of the capitalist economy. With a turbulent world confronting us today with one problem after another, including inflation, the global currency crisis, pollution, and the like, the truth of this work compared to the theories of bourgeois economics is becoming increasingly clear.

There is, however, one more major difference compared to bourgeois economics. That is, Capital not only clarifies the essence of the economic phenomena of capitalist society, but also provides a foundation for scientific socialism by clarifying the fate of capitalist society, telling us where exactly it is headed.

Hajime Kawakami spoke of Capital as a work that provides the only escape route for those who are suffering and consumed by worry under present-day society, and for those who have sunk into despair, and I think that Marx's book provides direction for such people to live, offering a scientific outlook and encouragement for their struggles.

In my own case, I started off with the study of philosophy, and considered the question of how human beings should live, but later I made the transition from philosophy to political economy. Fortunately, though, this was Marxist political economy, so it was not as if I were entering a whole different world. The idealist philosophy I had dealt with thought of man as being supra-historical and beyond class. And the same was said to be true of human life, with the way of living in ancient or modern society being the same, and there thus being a commonality between those who are satisfied with the current society and think day and night of how to preserve it, and those who are suffering under this society and thinking day and night of how to escape from it as soon as possible. This view is not only unscientific, but a deception. I think I have learned from Marxist political economy, scientifically and concretely, how life is led under today's society. Unlike modern [i.e. bourgeois] economics, this is a study of the economy that also deals with our way of living.

Capital is first of all a work of Marxist political economy of this nature, but the method applied in the book also has its own particular significance.

Lenin spoke of Marx as not having written a special book on logic but having a concrete book on logic called Capital. This is indeed the case. And the dialectical method applied in it teaches us a splendid point of view, way of thinking, and investigative method. Works such as Euclid's writings on geometry, Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, and Darwin's Origin of Species are specialist books on science but at the same time each of these classics have a lot to teach us about methodology. And this is particularly true of Marx's Capital as well.

This is because Marx consciously adopted a clear materialistic standpoint, fully assimilated the achievements of Hegelian logic, and consciously adopted a dialectical method.

There are all sorts of people, from various segments of society and professions, avidly studying Capital, including many in the natural sciences. One reason for this, as I noted, is the question of how human beings in today's society should live, and those in the natural sciences, knowing the position of their field and themselves within society today, are particularly interested in this question of how to live. They also are interested in studying the method of Capital. I think most of you are aware of the famous examples of the interest of the physicist Mitsuo Taketani (1911-2000) and Shōji Ijiri (1913-1999) in the field of paleontology. A few years ago Professor Ijiri told me that he had studied Capital on his own before the war, had read through it twice after the war more methodically with others in his field, and then read it again carefully a fourth time on his own. So he has probably read it more than most of the specialists in the field of political economy.

There are many other natural scientists who are studying Capital. Last year I read with great interest Dojyō biseibutsu (Soil Microorganisms) by Tsutomu Hattori (1932-), which was published as a paperback by Iwanami Shoten. One reason I found the book interesting was that the laws governing the realm of microorganisms in the natural world are fundamentally the same exact sort of laws that govern society. Also, I found the author's method of description, which is to say his method, quite interesting. For example, instead of seeing the various microorganisms living on our planet as separate entities, he views them from the perspective of the evolutionary history of organisms up to now. The author also regards microorganisms in their reciprocal relationship with their environment. Finally, prior to elucidating the state of microorganisms today, he discusses the history of research leading up to the present moment. He is always looking back on how the history of research leading up to the present was sometimes deadlocked, or even ceased altogether, before another breakthrough was made to allow for forward progress. Written in this way, I found the book easy to understand and fascinating.

I had a feeling that the author may have read Capital, and I mentioned this to him in a postcard I wrote to express how much I enjoyed his book. It turns out that this was indeed the case. Political economy and the study of microorganisms are very much separate fields, but we can come across cases such as this Tsutomu Hattori. Researchers in a variety of fields within the natural sciences are reading Capital, in part because of their interest in its method.

This is a bit off-topic, but I continued to correspond with Professor Hattori and he sent me a new year's card recently that informed me of his recent research. Apparently last summer he happened to come across a peculiar organism that only grows by consuming innutritious rather than nutritious substances, and since making this discovery he has become completely captivated by the study of this organism to the exclusion of everything else.

Professor Hattori mentioning how it is possible to be captivated by the discovery of something within nature is one of the most delightful anecdotes I've encountered this year. Marx, likewise, even though his field of study was different, was struck by the peculiarity of things, such as the fact that the commodity, in addition to its natural form, has a supra-sensual value-form that seems to be its natural attribute of the commodity, even though political economy prior to him had not been interested in this. He also noticed how peculiar it is that there is money within the world of commodities. Further, he thought it peculiar that the exchange between capitalist and worker is necessarily seen as being based on the principle of equal exchange even though profit and wealth are generated on the capitalist's side while only poverty is reproduced on the side of the worker; and that the relation between capitalist and worker is one of rule and subordinance despite its appearance as a relation of liberty, independence, and equality.

Marx found these phenomena of capitalism to be strange, not only because he was an outstanding scientist but because he adopted the standpoint of the working class that suffers under the society governed by capitalist relations and takes the most critical stance toward it. Because of this, Marx was captivated by the peculiarity of this reality and dedicated his life to practical and theoretical solutions, thereby achieving the magnificent discoveries presented in Capital.

Developed capitalism in Japan today is much more deeply contradictory than that of Marx's age, and more full of peculiarity. The starting point for those setting out to study political economy is the awareness of this strangeness. Nikaku Shofukutei, in a discussion with Kyosen Ōhashi for a magazine article, said that a feeling of anger is a force for artistic creation, so that he is always angry or seeking this feeling of anger somewhere. I think this view applies to the social sciences as well. If a person does not find modern society particularly strange, or is not angered by it, this will not lead to very profound research, and an awareness of the very need to study political economy would not be felt in the first place.

It is often said that occupying the standpoint of the revolutionary proletariat results in biased the research of social science, so that objective truth cannot be attained, but this is completely wrong. In fact, this standpoint generates a desire for study, and sustains it, so that it is one of the most important conditions for attaining objective truth. There are class-related differences for truth itself, but being critical and class-oriented facilitates the discovery of truth. The significance of class partisanship within the social sciences is that the discovery of the truth is painful for the bourgeoisie whereas the proletariat welcomes it.

To approach this from a different angle, if "method" is understood as a necessary condition for arriving at the truth, it could be said that Marx becoming captivated by the peculiarity of the contradictions of capitalist society is an important trait of the method of Capital.

Let's now take a look at the intrinsic method of Capital. Marx called himself a follower of Hegel because he profoundly studied Hegel's dialectic and exhaustively assimilated its valuable assets, but at the same time, as is well known, he said that he had to reverse the dialectical method of Hegel because it was standing on its head. The reversal of Hegel's dialectic is Marx's dialectical method applied in Capital.

Well, what does it mean to say that Hegel's dialectic is upside down, and that Marx turned it right-side up? First, let's look at the case of Hegel's dialectic.

Hegel thought that the various things within the world, as well as the various ideas and concepts that are the reflection of these things, at first seem to be all separate from each other, but that in fact the material world and the world of ideas make up an organic totality because an originally single thing, through its internal contradictions, generates one new thing after another, splitting into parts and becoming enriched and diversified. Thus, in order for us to truly understand these things and concepts, instead of treating them as something given that is discovered, and considering each individually, it is necessary to trace the history of their generation, and indicate the necessity of their determinative being that could not be otherwise. This was in fact a tremendous discovery on the part of Hegel, and simply put this is the dialectic method that Marx profoundly learned from him.

In a word, Hegel thought of things, and the cognition of them, in this manner, and clarified the limits of what is called the "analytical method." This method, based on the Intuition and Representation[1] of a given thing, analyzes its elements and reaches the level of a scientific concept by then synthesizing them; but according to Hegel, in terms of only dealing with posited facts, and in terms of the fact that the elements abstracted from out of concrete truth are the abstract universals of formal logic rather than the concrete universals that lead to the necessity of a given thing, this certainly does not provide a demonstration of the necessity of the existence of the thing. This is a perfectly correct criticism of the analytical method based on a dialectical, developmental view.

Hegel the idealistic philosopher, however, separates the thoughts within our brain from the material world that is the object of these thoughts, as well as from our own material brain that is the bearer of these thoughts, thinking of thoughts instead as things that move independently and as a real existence, whereas the world is seen at best as an alienated form that is the mere external appearance of this real existence. Moreover, as Hegel adopts a dialectical perspective, concepts that are merely the product of our brains are seen as themselves being real living things, and since he does not rely at all upon Intuition or Representation, he regards the backbone of the developmental process of reality, and the dialectical method itself, as being a process whereby more abstract concepts generate, through internal necessity, the concrete concepts. His dialectic is upside-down in terms of viewing the process of thought as being identical to the developmental process of reality.

Still, as I noted already, Hegel was perfectly justified in seeing the limitations of the analytical method. However, by seeing the dialectical method as a process of self-development from a concept as this sort of living totality to the next concept as a living totality, this analytical method inevitably came to be eliminated overall.

An actual thing certainly cannot analyze and synthesize itself, so Hegel's dialectical method also naturally has to draw upon Intuition and Representation. The primary trait of Hegel's upside-down dialectic is manifested in the fact that it ostensibly, if not in actuality, eliminates the analytical method that is the foundation of the scientific method.

This point is quite important so I'd like to provide a somewhat more concrete example of this.

In his study of logic, Hegel speaks in detail about what he views to be the true method of all science, but he starts off, as you know, with the concept of Being, and passes through the concepts of not-Being and Becoming. What is the significance of him moving from this abstract concept toward concrete concepts? As Hegel himself notes in his Shorter Logic, the great Heraclitus's view of the world, which imagined it as an unending process of generation and passing away, analyzed this and uncovered the element of Being and the element of non-Being, and said that Becoming is actually an unending shift from Being to non-Being, and from non-Being to Being, and that this is the process of attaining the concept of Becoming as the unity of these two elements. The process involving Being, non-Being, and Becoming is a process that can only be carried out within the thinking mind, and is certainly not a process of reality.

Hegel, however, twists things around so that the mere abstractions within the brain of Being and non-Being are seen as actual entities, with them necessarily shifting on their own, as Being to Nothing, and Nothing to Being, and the two of them into Becoming.

As this clearly shows, Hegel is in fact very much carrying out an analysis of reality. There is no way that a scholar as great as Hegel would not analyze facts. If Hegel had not analyzed facts at all, his logic would not have been able to have such precious and rich content. It would have been like a castle in the air.

However, in Hegel's theory of idealism he was compelled to ostensibly reject analysis. The Uno school of political economy, imitating Hegel's ostensible stance, have rejected analysis, saying that the dialectical method must be a process of the self-development of concepts.

In Hegel's logic, following Becoming, one arrives at Determinate Being. What is the actual meaning of this movement? This means that in the world reflected within our Intuition, there are various things that have a certain fixed nature that exist, and these things seem to move and to change. When we analyze the image of this world, we find that the things (Determinate Being) which seem to seem to be fixed are in fact in movement, and that what forms the basis of this is Becoming. Upon this basis there is the process of thought toward attaining the concept that there are things that are relatively and temporarily fixed, namely Determinate Being. In this process, the cognition of the world within our minds progresses, moving from a more abstract view of the world, and then upon this basis moving to a more concrete view of the world.

In the case of Hegel, however, who does not distinguish between the process of thought and the process of reality, he struggles and twists things around, attempting to make this a process where the concept of Being exists independent of both the world and our minds, and that through its own power inevitably moves toward the concept of Determinate Being, without even the Representation of Determinate Being. In fact, the world exists outside of our minds, so that the Representation, or image, of the world, which is Determinate Being and its changes, is already posited. It is just a matter of us then analyzing this to grasp it at a more profound level, which is perfectly natural, but the perspective of Hegel's idealism was quite incapable of accepting this.

To take one more example: Hegel, in the Doctrine of Being within his logic, which includes the above process, the concepts of Quality and Quantity, and the concept of Mass as the identity of the two, are discussed in three separate parts. Today I think the relation between these three concepts can immediately be understood by anyone. Because an actual thing is always a unity of quality and quantity, up to a certain point its quantity can change irrespective of quality, but there is a limit to this, and once exceeded, quality will change. Given this, a certain quality exists as that limited by a certain range of quantity. As you know, in Capital Marx spoke of this law of the transformation of quantity into quality as one of the discoveries of Hegel.

Hegel analyzes this fact in terms of the constituent elements of quality and quantity, abstractly considering each separately, and then attaining the concept of Mass as their synthesis. This is also because a real thing that is a unity of quality and quantity is first able to be well understood (and conceptualized) by adequately elucidating the nature of each of its constituent elements, quality and quantity. Further, it is also the case that living reality cannot be dealt with as it is because the truth of a thing can be much more profoundly grasped by extracting one its parts to be purely considered. In the case of Hegel, however, despite in fact employing this rational method of cognition to profoundly grasp reality, he makes it seem as if this process of analysis and of synthesis is such that, taking our example of the concept of quality, it shifts to quantity according to its own internal necessity.

The process of the movement of concepts within the totality of Hegel's logic has this nature, which is the essence of his exceedingly mystical dialectical method. At the same time, however, I think we can see the degree to which Hegel actually employed an analytical method as well.

What, then, is the nature of Marx's dialectical method which is the reversal of Hegel's dialectic?

In a word, the dialectical method of Marx's, who stood on a position of materialism, is a developmental method added to the analytical method at its base.

The analytical method, to repeat, begins from the given facts, in other words the Intuition and Representation of the object, and arrives at a concept of it by means of analysis and synthesis, and the logical thought process to carry out this analysis and synthesis remains within the range of formal logic, not being at all dialectical.

This analytical method, however, is also the method of classical political economy as well as the method generally employed in the natural sciences. The classical economists, and generally those engaged in the natural sciences, adopted a materialistic standpoint, albeit not consciously, and recognized that the objective world operated according to particular laws that are independent of human consciousness. Thus, instead of creating the truth from out of their heads, they sought it in the objective world. That is, they pursued the figure of an object as it appeared in front of them – the Intuition and Representation of the object – which was then analyzed and synthesized to be turned it into a concept. The logic employed to do this remained within the realm of formal logic.

In the case of Marx's dialectical method, not only does it include as its basis the analytical method of classical political economy, it actually employs this method to an even more rigorous extent. This is because the analytical method, generally speaking, is the basis of thought, and therefore the basis of the scientific method.

However, the analytical method has one limitation. It is able to show what a thing is by elucidating its essence, but it is unable to clarify its necessity in terms of why it could not be otherwise, or explain the how and why of the object. Furthermore, this method is unable to explain the necessity for every thing in the world to eventually cease to exist or the necessity of a transformation into their opposite. Considering this, therefore, this method is unable to completely grasp exactly what a thing is.

Given this, a developmental method is added to the analytical method that the basis. This is the dialectical method of Marx, which is also the concrete meaning of reversing Hegel's upside-down dialectic.

Stated in this way, a good many of you are probably dubious. I suspect you may be thinking that analytical method of classical economy and Marx's dialectical method are in a relation of not being easily compatible, and are instead quite distinct from each other; or that even if they were compatible, this manner of thinking makes Marx's dialectic out to be something dualistic and mechanical, whereas it should be smooth and integrated.

But if we look at the part of Marx's introduction to Grundrisse that discusses the method of political economy, we can clearly see the importance he attached to the analytical method of classical political economy. Marx says that bourgeois political economy sets out initially from the economic situation in a given, concrete country, and through analysis reaches the concept of class, and then goes on to reach the underlying concepts of capital and wage labor, and from there the concepts of value and price, and then further the concepts of the division of labor and need, thereby moving from the concrete phenomena gradually to arrive at the most abstract concepts, but once this point is reached, political economy then sets out on the opposite journey starting from these abstract, fundamental concepts, to gradually progress toward concrete concepts, on a path that leads ultimately to the economic situation in a concrete country that was the starting point. Of these two methods, Marx says that it is the second one – which is to say the path leading gradually upward from the abstract, foundational to a scientific grasp of concrete reality – that is the scientifically correct method.

Because this is the scientifically correct method, the method of Marx in Capital is clearly also this method. This is merely saying, however, that there is an upward movement from the more abstract concepts to the more concrete ones, and certainly does not mean that the more abstract concept generates a more concrete concept from out of its own internal necessity, or that these logical steps correspond to historical development. To say that the division of labor begets price, or that class begets the concrete economic situation of a given country, so that the former historically develops into the latter, is no different from the mysticism of Hegel's dialectical method that we have looked at, and a complete impossibility. The upward process of the method is not a manifestation of an actual process, but rather corresponds to the world of thought, and this is merely the move from one premise to the next one following the laws of formal logic. Marx ends this discussion by reflecting on the history of the method of classical bourgeois political economy, saying that it should not be overlooked that the scientifically correct method is the method of classical political economy.

This part of the introduction is where Marx deals with method in the most detail, but for some reason when his method is discussed this is not often cited. But this seems to be a passage which is saying, with no room for doubt, that even though the method of Capital is not limited to being the analytical method of classical political economy, it is indeed also an analytical method.

In this way, saying that Marx's dialectical method is based on the analytical method means that each step of its unfolding process of development is based upon this method, but this is not the extent of the matter. This means, in particular, that the concepts of capital and money, which are the basis of this developmental method, are obtained through an analytical method that starts out from purely given facts. This is because Marx accepts these facts as given things discovered within the developed capitalism that was in front of his eyes. Science, contrary to the view of Hegel, not only thinks of the objective world as the absolute given premise, but also takes capitalist society as a given fact rather than posing the question in terms of its unfolding from primitive human society through internal necessity. Thus, the key concepts of capitalism – commodity and capital – are obtained not through a developmental, dialectical method, but rather through the analytical method. The developmental unfolding is subsequently carried out using these concepts as the basis, explaining all of the phenomena pertaining to commodity and capital as necessary things.

However, these concepts of commodity and capital have in many cases been subject to distortion through a Hegelian dialectical development, and I would like to look at what happens in such cases.

At the very beginning of Capital, Marx speaks of how the wealth of capitalist society presents itself as an enormous collection of commodities, and that his investigation will begin with the analysis of the commodity because the individual commodity presents itself as the elemental form of this wealth. Thus, his starting point is not the concept of the commodity but the figure of the commodity as it sensually appears to us, the Intuition and Representation of it. Marx then analyzes the commodity as it is in our eyes, clarifying the nature of its elements – use-value and exchange-value – and then arriving at the concept of the commodity as the unity of these two elements. The concept of the commodity is not the starting point but rather the outcome. If instead the concept of the commodity were the starting point, Capital would be a work forced upon the reader without any demonstration, so that it could not be considered scientific. Marx starts with the fact of the commodity, which no one, not even his opponents, can deny. And following irrefutable logic, he analyzes the commodity and then synthesizes it, thus arriving for the first time at the concept of the commodity.

Marx devotes more attention to the analysis of exchange-value because, of the two elements of the commodity, it is exchange-value that turns a simple use-value into a commodity. But in this case as well he begins from the image of exchange-value that everyone is aware of, namely, the way it presents itself – as the exchange ratio between one use-value and another – which seems to be a mere relative relation. From this starting point, Marx carries out an analysis based on logical reasoning that leads to the concept of value.

Thus, the concept of the commodity, as well as the concept of value that is one of its moments, is arrived at from the image of the commodity and exchange-value that the reader is familiar with. It is certainly not the case that there is a developmental unfolding from an a priori concept. To this extent, Marx is completely adhering to the analytical method in general.

Regarding the sort of logic that Marx employs in this analytical process, it is very much the normal sort of formal logic, and this is firmly adhered to. The logical relations between concepts (use-value, exchange-value, value, concrete labor, abstract labor, and finally the commodity itself) are relations of formal logic, not dialectical in any way.

Marx first of all analyzes the commodity in terms of its two elements, use-value and exchange-value; the former is distinguishable qualitatively and the latter quantitatively, and the former is a natural attribute whereas the latter is a manifestation of a social relation. But this analysis remains within the realm of thoroughly formal logic, just as the natural scientist analyzes water to arrive at the two elements of hydrogen and oxygen.

In Japan, despite it being noted that the commodity is comprised of these two different types of things, Marx's term Zwieschlach has been translated as "two conflicting things" (nisha tousouteki), which is a mistaken interpretation that introduces a Hegelian dialectical method that starts from the contradiction of the commodity. Everyone should know that, seen straightforwardly, Marx is distinguishing the two elements of the commodity while contrasting them, saying that one is this way and the other is that way. And one can only first speak of a contradiction between the two elements of the commodity once each element is understood. The correct translation of the term is thus "dualistic" (nimenteki).

What is the case, then, for the analysis of exchange-value, which constitutes the core of the analysis of the commodity? Here the analysis moves first from exchange-value to the intrinsic value of the commodity, and Marx says that a commodity will have various exchange-values depending on the other commodity it is exchanged with, but that since these various exchange-values are all the same thing there is a value particular to a given commodity, so the various exchange-values are merely the modes of expression of this value. This is precisely the reasoning of typical formal logic.

Next, Marx sets out from the analysis of this value to uncover the abstract labor as its substance, and as you know, commodities with different use-values can be quantitatively compared to each other as values, and if the respective quantity of this value is appropriate they can be equated and exchanged for each other. But for this to happen, there must be some common equivalent between them, which can be nothing but the fact that they are both the crystallizations of abstract labor. And Marx deduces this using irrefutable reasoning, although it is nothing special apart from formal logic.

Now let's consider the primary reciprocal relations between the concepts that Marx elucidates.

First of all, there is the relation between use-value and exchange-value. Here it seems that use-value develops into exchange-value, and in particular that value is limited by use-value and that use-value is also limited by value. But what Marx is saying concerning use-value is simply that the use-value of a commodity is the useful natural quality that a product of labor has for us. Thus, it is not a value-like thing at all. Regarding this, he says clearly that use-value is the material content of wealth, regardless of the form of society. In Grundrisse, Marx expresses this by saying that the taste of wheat will not inform us of whether it was grown by Russian peasants or is a product of capitalistic agriculture. And a use-value is possible apart from value. In our society, use-value is the material bearer of exchange-value, Marx says.

Use-value is clearly the unilateral premise of value, or what Hegel calls an abstract universal.

Thus, in the relation between use-value and commodity as well, the former is the unilateral premise of the latter, so that it is a matter of indifference, as far as a product of labor and its use-value are concerned, whether or not it is a commodity.

What about the relation between concrete labor and abstract labor? There is a view that they are in conflict and contradiction with each other, but this is not in fact the case. Marx says instead, bearing in mind the classical school of political economy, that they are distinguished as two different things. If the two were in contradiction and conflict, then labor would be extinguished so as to become something else. The actual labor of human beings is always concrete labor in one aspect and abstract labor in another aspect. There is no dialectical relation here.

Finally, what can be said about the relation between abstract human labor and value? Often it is heard that the former is historical and related to value, so that there is a dialectical relation between them, but as we have just seen this is not the case. In the section where Marx considers the fetishistic character of the commodity, he looks at the content of value, but when he says there that labor in one aspect is abstract labor, this is said to be a physiological truth and he points out that the quantity of abstract labor is an issue in any society.

Abstract labor itself has this nature, but only in commodity society does it become a social thing that expresses the social quality of the labor of individuals, thus becoming a social substance. Abstract labor is a unilateral premise for value, so it is not the case that they are in a relation of premising each other, nor is it the case that abstract labor begets value.

From this we can see that the analysis of the commodity is carried out on every point using the analytical method.

Now let's turn our attention to the case of capital.

Here as well, there have been various attempts to view capital as the inevitable development of the concept of commodity and the concept of money. And there have been efforts that forgo the assistance of the Representation from commodity and money, to see capital as the outcome of an a priori development. However, as we can see in the discussion of the "transformation of money into capital," Marx is certainly not advancing such a forced argument. Rather, he is recognizing the fact of the circulation of capital in addition to simple commodity circulation, and he analyzes the fact that surplus-value is generated as the result of this circulation of capital. In the process of his analysis, Marx raises all of the possible causes within the process of circulation, examining each one, and he clarifies the fact that not all of them could generate surplus-value, which can instead only originate from the production process. And finally he demonstrates that surplus-value can only arise from the capitalist's purchase of the special commodity labor-power and the consumption of it within the production process.

What sort of logic are we dealing with here?

This logic is precisely the typical method of demonstration, the reasoning of formal logic also employed by natural scientists.

Meanwhile, if we look at the relation between money and capital, it is certainly not a dialectical relation where money begets or develops into capital. This is fundamentally different from the developmental relation of commodity into money. Because money is only first able to become capital when wage labor exists in society, money is precisely the simple premise for capital, or what Hegel calls an abstract universal.

From the discussion above, I think we can see that, directly speaking, the concept of capital is obtained through an analytical method that starts from the Representation of capital that is a completely given premise. This is natural in the case of Marx because, just like the case in every field of science, not only does he assume the world as a whole, but he also starts from the given premise of capitalist society that is his object of study.

Thus, after obtaining this fundamental concept, on the basis of the given Representation, via the analytical method, the concept is then used as a basis, with every phenomenon of commodity and capital then being developmentally unfolded as its necessary phenomenal form. In this case as well, for each step of the development, Marx always has in mind the concrete Representation that the analytical method is applied to, but this will have to be discussed on another occasion.

Hegel, as well, as I touched on a moment ago, in fact employed the analytical method. In fact, it is safe to say that he employs this method at every step of the developmental process that at first glance seems to be speculative. The forms of his method, such as his thesis, antithesis and synthesis, as well as the negation of the negation, also display the form of the analytical method that we have just taken a concrete look at, with Hegel breaking down the two oppositional elements within the Representation of any given thing, and then reconstituting them. I think this is again because the analytical method is the foundation of thought, and therefore the foundation of the method of science, so for any knowledge to be considered to have scientific meaning it cannot do without this method. In the case of Marx's dialectical method, the analytical method that constitutes its indispensable moment, which Hegel also uses despite ostensibly rejecting it, is something accepted as is.

It is extremely important to clearly recognize that the analytical method is the basis of the dialectical method. We have looked at the process of Marx's analysis of capital, and how he examines every possible case, following a method of reasoning where everything apart from one case is white, and only that one case is black. No matter how much we may speak of the dialectic of a thing, if the concept of the thing that is its foundation is based on only one or two of all the possible cases, this will be far from sufficient. Often we can see examples of those who speak of the dialectic while ignoring the fundamental logic of formal logic.

Moreover, there are also cases where what is critically important is not so much the dialectic itself but the elucidation of the essence of a thing through the method of analysis. Marx, as is well known, said that the best parts of Capital are the tracing back of the creation of value to abstract labor and the pure analysis of surplus-value; to which he also added the grasping of wages as the value of labor-power. The former two, as we have seen, were each discovered according to the analytical method. And wages were also clarified though this method, not through a developmental unfolding that begins from some a priori concept. All three of these are generally seen as the most important discoveries made by Marx. Such discoveries of the essence of things have the utmost critical and revolutionary significance of a nature that infuriates the bourgeoisie. And this forms an important constituent element of the critical and revolutionary character of the dialectical method.

It is not generally understood, however, that Marx's method in Capital is the addition of what could be called an inherently dialectical method to an analytical method. This, as noted already, is because such a view is seen as being dualistic and mechanical. Here I want to consider this point a bit further from a different angle.

Engels, in Anti-Duhring, speaks of how scientific specialists in the future will come to have a broad familiarity with other specialties other than their own specialty alone, and come to know the position of their area of specialty within the totality of the knowledge of these other areas; while on the other hand, he says that philosophy will no longer be studied in general, without being based on knowledge from the demonstrative sciences, so that there will no longer be room for a special philosophy to exist above science. Following this, Engels says that there would only exist formal logic, as the principles of thought, and dialectics. This passage is quite well known so you are no doubt familiar with it.

Formal logic and dialectics remain. If formal logic, as has been thought in the past, were indeed incompatible with dialectics, Engels would not have spoken in this manner. Nor would he have said this if formal logic were one moment within dialectics that is absorbed within it.

This indicates well the independence of formal logic vis-a-vis dialectics. The same is true for the relation between the analytical method and dialectics, and those skilled in thinking dialectically not only employ formal logic along with dialectics, but actually adhere more strictly to formal logic than those who think solely in terms of formal logic.

All types of development are of this nature. The commodity is transformed into money, but this does not mean that the world comes to be full of money alone. Rather, commodities co-exist with money and the quantity of commodities increases further and further.

In discussing "monopoly," Lenin says that free competition is the fundamental characteristic of commodity production and capitalism, and that this fundamental characteristic of commodity production is negated, becoming its opposite as monopoly. But he goes on to say that monopoly emerges from out of free competition, and moreover says that monopoly exists alongside free competition, on top of free competition, and for this reason the contradictions of the age of imperialism are even more complex and harsh. In speaking of monopoly, this does not mean that there is only monopoly. It exists alongside of free competition, upon the basis of free competition. Living things emerge from out of inanimate things. This does not mean, however, that inanimate objects cease to exist, but rather remain as the earth as a whole qua inanimate environment of living creatures. Even though animal life emerged from out of plant life, this does not mean that plants just vanished, but that they remain, coexisting with animals.

If we examine the highest nerve center and brain of a frog, and stimulate the frog's leg with a drug and with a pin, even if the brain has been removed, there will be a response. If a piece of paper coated with the drug is applied to this leg, it will be removed by the other leg. This high-level action is performed even if the brain is removed. This means that the low-level nerve center and the nerves are relatively independent, and it is upon this basis that the brain then controls them. At the same time, however, other organisms exist alongside frogs that are equivalent to this lower mechanism of the frog.

Socialism emerges from out of bourgeois liberalism, democracy and nationalism, but this does not mean that socialism views liberalism and democracy as matters of indifference. Rather, it takes freedom, human rights and national independence even more seriously, and in order to protect this sincerely considers uniting with bourgeois liberals it coexists with.

This is the case for all development. From this I think we can also understand the relation within the method of Capital between formal logic (or the analytical method) and dialectics. Marx's dialectical method is this formal logic plus dialectics.

Hegel saw the dialectic organically as a coherent whole, and today as well this Hegelian way of thinking can often be seen, such as the dialectic of Sartre.

The gist of scientific cognition is divided into the three stages of (1) the sensual stage, that begins from the Intuition and Representation of a given thing, (2) the understanding stage, where the thing is analyzed to uncover its essence of substance, changing it into a concept, and finally (3) the dialectical stage, in the narrow sense, where based on this concept various phenomenal forms of the thing and developmental stages are developmentally unfolded as its necessary phenomenal forms, and the necessity of the extinction of the thing is elucidated. In Hegel's upside-down dialectic, the first two stages, which are within the realm of the analytical method, are removed, whereas in Marx's dialectical method I think it can be said that they exist alongside the third stage, not only in the (downward) process of inquiry, but also in the (upward) process of presentation that is method of Capital.

The discussion thus far has concerned the main characteristics of Marx's dialectic from the angle of it being the reversal of Hegel's dialectic. To add a word at the end here, Hegel's dialectical method sees things in a developmental way, but as we have seen, although the forms seem to be the genesis of real things, the content of this is the developmental history of subjective cognition. So it is perfectly correct for Hegel to say that the steps of this logic correspond to the steps of the history of philosophy, but he twists this into being the process of reality.

Compared to this, Marx clearly divides the process of reality from the process of cognition, and the primary method of Capital traces the real developmental process of capital. This is something that can barely be seen in the case of Hegel's dialectical method. This was created by Marx. But at the same time, in the fourth part of his work, Theories of Surplus Value, there is the history of the development of his own theory. In Grundrisse, as you know, the two developmental histories are side by side. Thus, not only does he speak of the developmental history of the object of study itself, but also describes the developmental history of his own research, and of particular importance is the criticism of views opposing his own.

One more method of Hegel is that he does not recognize existence independent of consciousness, thus making no distinction between the upward and downward methods, so that his dialectical method is simultaneously the upward method as well as the downward method. And this leads to confusion and mystification. Marx instead clearly divides the upward from the downward method, which is one aspect of his reversal of Hegel's dialectic.

My discussion has been far from adequate, but it will have to suffice for today's examination of the method of Capital in terms of being a reversal of Hegel's upside-down dialectic.

1. The Japanese terms used here, chokkan and hyoushō, correspond to the German terms Anschauung and Vorstellung and I have translated them throughout as Intuition and Representation.