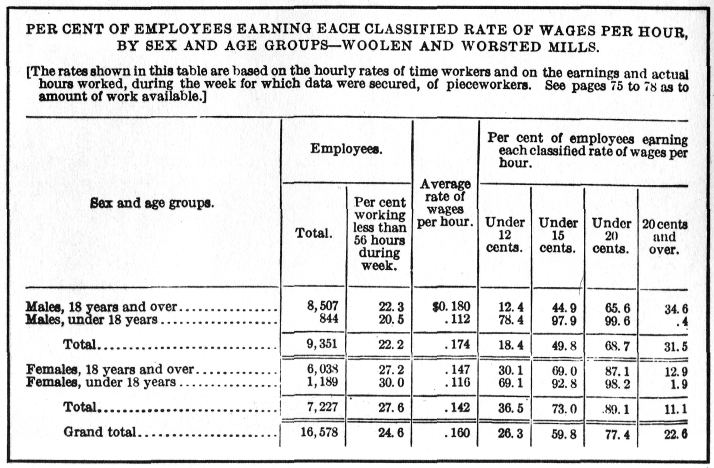

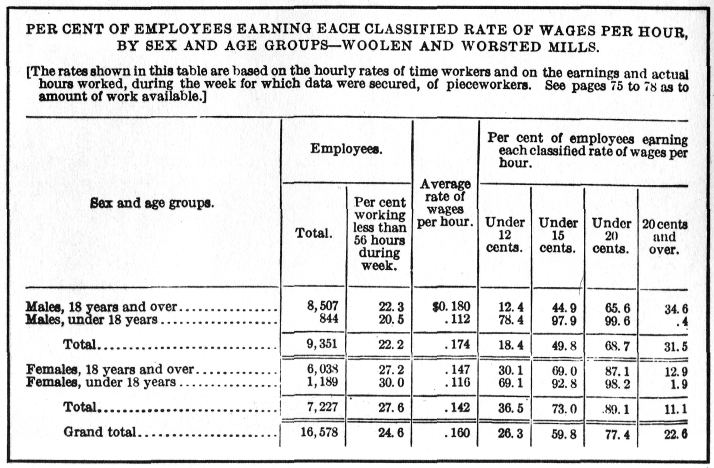

Almost three-fifths (59.8 per cent) of the 16,578 woolen and worsted mill employees earned less than 15 cents per hour, and more than onefourth (26.3 per cent) of the total number of employees earned less than 12 cents per hour. The proportion earning 20 cents and over per hour was-'slightly less than the number earning under 12 cents per hour, the percentages being 22.6 and 26.3, respectively.

The table on page eight shows for the employees of each sex and within each age group the average rate of wages and the per cent earning each classified rate of wages per hour. The classified rates are shown in the form of cumulative percentages.

From the above table it is seen that twice as large a proportion of the females as of the males earned less than 12 cents per hour. Seventy-three per cent of the females and 49.8 per cent of the males earned less than 15 cents per hour. Eleven and one-tenth per cent of the females and 31.5 per cent of the males earned 20 cents and over per hour.

The average rate of earnings of the 8,507 males 18 years of age and over was 18 cents per hour, which was 3.3 cents per hour above the average for the 6,038 females 18 years of age and over. The average rate earned by the 844 males under 18 years of age was 11.2 cents per hour, which was 0.4 cent per hour less than the average earnings of females under 18.

Practically all the textile mill employees in Lawrence live in wooden tenement houses. The most, usual types of these are either three or four story buildings and, in the more thickly settled portions of the city, tenements occupy both the front and rear of the lots. These rear tenement houses can usually be reached from an alley, but the principal entrance, and in some cases the only entrance, is through a narrow passageway between the front buildings.

.... The following paragraphs are extracts from the manuscript of the Report of the Lawrence Survey:

... The center of Lawrence has the largest number of large frame houses and the largest number of rear houses. With Boston's brick center excepted, the map of Lawrence center is the worst in New England.

The two half blocks on the east end of Common Street adjoin each other on the south side of the street and with one-half of the surrounding streets contaIn 8.2 acres. All the houses but three are wooden. This is the greatest concentration of population in wooden houses in any 3 acres in the State of Massachusetts. No 3 acres In the State exceed it except at the infamous centers of Boston, where the houses are predominantly 'brick.

The present building regulations of Lawrence are inadequate, as is indicated by the following extract from the report of the inspector of buildings of Lawrence for the year 1910:

Each year I have recommended that the city council take up the matter of revising the building ordinances. That suggestion is not out of place at this time. Last year and the year previous I recommended that the building ordinance be revised along the lines laid down by the National Board of Fire Under writers. This year I make the same suggestion. Under the present ordinance there is no provision for foundations, thickness of brick walls, size of floor timbers or columns, floor loads, lighting or ventilation of building, protection against fire, or any of the important matters which a building ordinance should restrict. Of course, In a general way, some provision has been made in the ordinance to cover some of the matters above mentioned. The law should be specific and accurate in order to be effective.

With the compactly built squares, the large percentage of wooden structures, the crowding within the apartments in the central sections of Lawrence, and in many tenements very poorly lighted stairways, the fire risk both to life and property is very great. The apartments, practically without exception, are supplied with city water, and in every case the apartments are provided with water-closets. In a few of the older houses the water-closets have been placed in the hallway and one closet must be used by the occupants of two apartments, but in a number of the older houses and in all of the newer houses every apartment is supplied with a separate water-closet.

In studying conditions in Lawrence, agents of the Bureau of Labor visited 188 households, the greater part of them being of the races representing the unskilled workers in the textile mills. Of the 188 households visited, 109, or 58 per cent, kept lodgers or boarders. The total number of persons in the 188 households was 1,309, more than one-fourth of them being lodgers or boarders. The average number of persons per apartment was a little less than 7, and the average number of persons per room was one and one-half. One hundred of the 188 households occupied apartments of 5 rooms and 65 occupied apartments of 4 rooms each. In one case 17 persons occupied a 5-room apartment; another household of 16 persons occupied a 5-room apartment, and in another case a household of 15 persons occupied a 5-room apartment.

The rent per week varied from $1 to $6, but the amount most commonly paid was $2 to $3 for a 4-room apartment and $3 to $3.50 for a 5-room apartment.

One of the most crowded sections of Lawrence is occupied by South Italians and the rent they pay per room, while somewhat less than was paid by families of that race in the most congested sections of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, is higher than that paid by households of that race in the most crowded sections of Chicago, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Milwaukee. This comparison is based on the Bureau's study in Lawrence and on the Immigration Commission's studies of immigrants in cities in 1907 to 1909, as published in volume 26 of the commission's reports.

Among the 188 households there were 20 families where the husband was the sole wage earner and where there were no lodgers or boarders. The lowest earnings for these 20 families was $5.10 per full week, and the family consisted of husband, wife, and three children. The, largest family among the 20 consisted of husband, wife, and five children, and the husband earned $11.09 per full week.

Among the families studied there were 176 with both husband and wife; the wife as well as the husband was employed in 58 of the 176 families.

The indispensable pieces of household furniture found universally are the kitchen stove, kitchen table, kitchen chairs, and beds. Of these articles only the kitchen stove is necessarily expensive. It is purchased by the family usually on the installment plan. The cost of a stove varies from $20 to $50; but the usual price paid for a new stove is about $35.

In many households only one table is found. This may be either a kitchen or a dining table, which serves the purpose of both. In the poorer houses the drop-leaf table is in demand not only on account of its low price, but also because it is convenient in crowded quarters.

According to the dealers visited, the only bedstead in demand among the immigrants of most races is the iron, painted with cheap white enamel. Italians, however, in many instances buy good brass beds, which are fitted with mattress and bed clothing of corresponding grade. Among the Syrians, as well as the Italians, the beds are usually well clothed if the occupants- of the house have sufficient earnings to provide anything more than food and rooms.

Two furniture dealers on Essex Street quoted prices on articles of household furniture of the grade commonly bought by families of the races from southern and eastern Europe. The first firm caters to this line of trade and does a large credit business in goods of medium and low grades. The prices as tabulated for this firm are for credit purchases, and in all cases the cash price is 90 per cent of the corresponding credit price. When goods' are purchased on credit, the terms, even on small purchases, are one-fourth cash and the rest in payments of $1 per week on a bill not exceeding $100, $1.50 per week on a bill not exceeding $150, etc.

The second store represented in the table is an old firm which has in addition to its trade among the immigrants a well-established trade among the more prosperous people of th city. Although this store carries a large stock of low-priced goods, it does not attempt to attract the immigrant trade of the community and sells to such customers only on cash terms.

It should be stated in connection with the study of retail prices that people in need of the articles of furniture, and clothing quoted do not always buy these things from the class of stores visited. In a shifting population like that of Lawrence secondhand articles of furniture are not hard to procure, and a person who has need of a kitchen stove, but can not afford a new one, may find one which will serve his purpose at a secondhand store. Secondhand dealers with large stocks are numerous, but prices from such firms can not, of course, be quoted, since the prices charged depend largely upon the state of preservation of the goods.

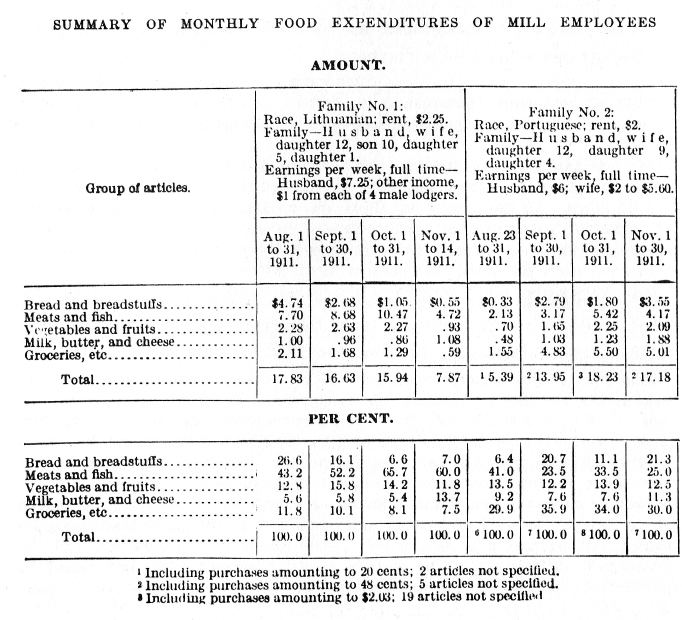

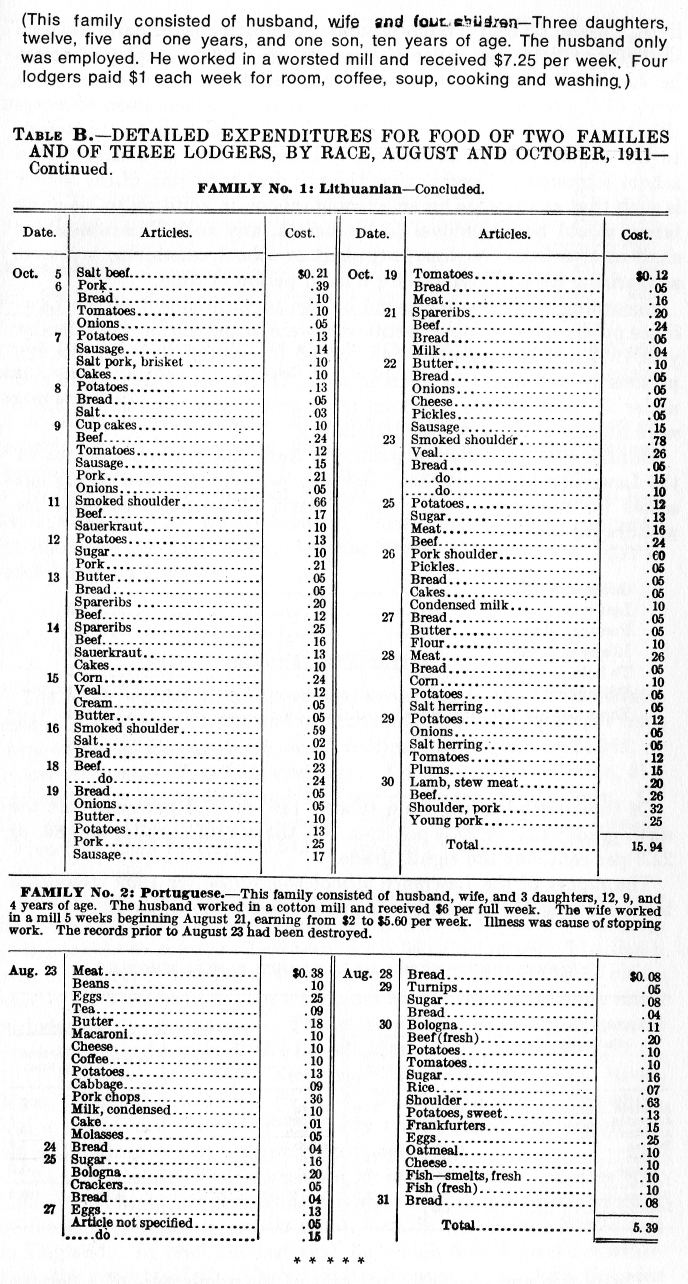

Among certain races it is very common for families to buy their groceries on credit, having all purchases entered in an individual account book which they keep in their possession. The slime practice is followed in the case of so-called "lodgers," or persons who for a specified sum are given lodging, coffee, and soup, and the services of the housewife as cook and laundress. Among the Lithuanians and Poles the method of purchasing on credit is very general. Among the South Italians some account books are to be found, but the Italians are bargain hunters and do not make a practice of trading exclusively with the firm with which they have an account. In a search for account books which represented the entire expenditures of the family for food, no Italian families could be found who traded entirely in this way. Owing to the fact that account books are almost, invariably destroyed when the account is settled, few were found covering any considerable period preceding the strike. Accounts only for two families and for four lodgers could be secured, and data concerning these accounts are here presented. These accounts show conditions just as they existed in those cases, but, of course, the number represented is not sufficient for any conclusion as to whether or not they represent conditions generally among mill employees. Books of a Lithuanian family, consisting of husband, wife, and four children all under working age, and of a Portuguese family, consisting of husband, wife, and three young children, were secured, as were also books representing the food expenditure of three lodgers, of whom one was Lithuanian, one Russian Polish, and one Russian.

The head of the Lithuanian family worked in a worsted mill, where he never made more than $7.25 per week. The wife was not a wage earner during the period covered by this schedule, for she had the care of a year-old child as well as of three other young children. She added to the family income, however, by keeping four lodgers for whom she did all necessary cooking and laundry work. The family from their own funds furnished each of these lodgers coffee or soup both morning and evening. Each lodger paid $1 per week, the customary rate among Lawrence Lithuanians and Poles for the accommodations just named. This household occupied an apartment of five rooms, for which they paid $2.25 a week. The account of this family begins August 1 and terminates November 14, 1911, on which date the grocer refused further credit because the family had become too heavily indebted to him.

The head of the Portuguese family worked in a cotton mill, where his pay never exceeded $6 per week. His wages did not serve to provide sufficient clothing in addition to rent and food, so in August his wife entered the mills in an effort to make money to buy winter clothing.

Earlier in the summer she had boarded two children of a neighbor woman who worked. For the care of the two children and for their meals she received $2.50 a week of six days. Work in the mills was slack, and she being slow could make only $2 to $5.60 a week. After five weeks' work she had to stop on account of illness. On the 1st of October this family received a present of $5 from relatives in another part of the United States, who heard of the wife's illness, and this money was given to the grocer in part payment of the account with him. This family paid $2 a week for an apartment of three rooms, one of which was too dark to read in at midday 951 a clear day.

There was an eighth-barrel bag of flour in the house at the time this account began (Aug. 23), and the wife baked a considerable proportioii of the bread used by the family, sometimes baking at night, while employed at the mills.

No data are available which enables a comparison to he made of prices in Lawrence with prices in other cities of the country. The Bureau, however, secured quotations from Lawrence for the purpose of showing prices which were paid by textile employees in that city. Among some of the races from southern and eastern Europe there is a great demand for stew beef, costing at the time of the strike from 10 to 14 cents per pound. There is also a large call for fresh pork, at about 16 cents a pound. Comparatively little butter is consumed by these races, but considerable butterine is used, and leaf lard and beef suet are purchased and rendered for use as a substitute for butter. Macaroni and spaghetti are important articles in the diet of the Italians. A considerable portion of the milk consumed by textile operatives is measured from cans, and this loose milk is generaly sold at 7 cents and the bottled at 8 cents per quart, but even with fresh milk at 7 cents a quart many families in Lawrence are unable to afford fresh milk and depend entirely upon condensed or evaporated milk.

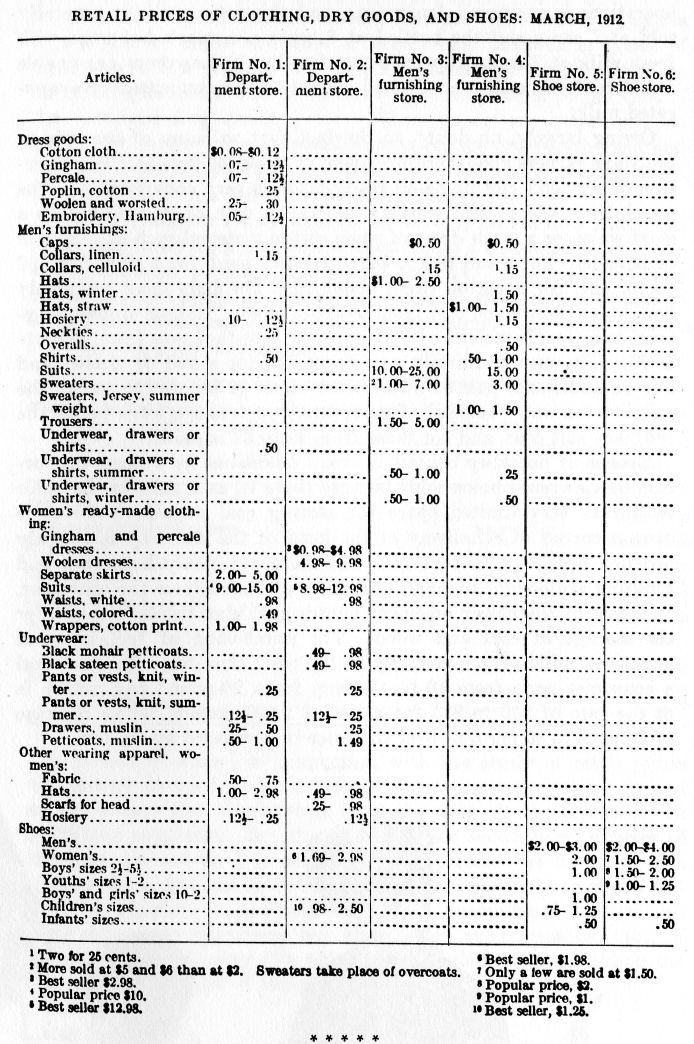

Owing largely, no doubt, to the fact that so many of the women are wage earners and, therefore, have no time for sewing, the proportion of women's clothing sold ready-made is very considerable. The usual dress sold to mill workers is a jacket suit, or odd skirt. with a shirt waist, or a wash dress of some cotton material such as gingham or percale. For a suit $10 to $12 is usually paid, for a skirt from $2 to $5, and for a cotton dress about $3. The hats most commonly bought by the women cost from 50 cents to $3. Italian women, however, wear scarfs instead of hats and for these they pay from 25 cents to $1. The men ordinarily pay about $15 for a suit of clothes and buy an additional pair of trousers for about $2 before the rest of the suit is worn out. Instead of overcoats, sweaters are worn under the ordinary suit coat, and for these from $1 to $7 is paid.

Fuel is of necessity bought in small quantities by a large proportion of Lawrence households because there is, as a rule, in the older tenements very limited space for storing coal or wood. In some cases a corner of a hallway at the head of the stairway is roughly boarded up for a foot or tw0, but more commonly both coal and kindling are bought in small quantities and used from the container. In many of the newer tenement houses provision has been made for the storage of coal and wood. The purchasing of fuel in small quantities adds very materially to the cost; thus for anthracite coal a consumer pays from 10 to 13 cents for a 20-pound bag, which is at the rate of $10 to $13 for a ton of 2,000 pounds, or an increase of from 40 to 80 per cent over the price if purchased by the ton.

The labor law of Massachusetts (chap. 514, sec. 56, Acts of 1909) states that "No child under the age of 14 years, and no child who is over 14 and under 16 years of age who does not have a certificate as required by the four following sections [sees. 57, 58, 59, and 60] certifying to the child's ability to read at sight and to write legibly simple sentences in the English language shall be employed in any factory, workshop or mercantile establishment." The age and schooling certificates must be approved by the superintendent of schools, or by a person authorized by him in writing, or if there is no superintendent of schools, by a person authorized by the school committee. The person issuing the certificate certifies that the applicant "can read at sight and can write legibly simple sentences in the English language."

The provisions of the labor law as to compulsory attendance at day or evening school extend to minors until 21 years of age, in so far as they are unable to read and write according to the test prescribed by the statute, i. e., such ability as is required for admission to the fourth grade of the schools of the city or town in which such minor lives. (Sees. 17, 66.) While a public evening school is maintained no illiterate over 16 and under 21 years of age may be employed unless he furnishes a weekly record showing his school attendance each week of the term; provided, however, that on presentation of a certificate signed by a registered practicing physician and satisfactory to the superintendent of schools, if there be one, or if not, to the school committee, showing that the physical condition of the holder is such that attendance on an evening school, in addition to his daily labor, would he prejudicial to his health, any such illiterate minor shall receive from the superintendent or school committee a permit authorizing his employment for a fixed period of time.

According to figures furnished by the superintendent of the Lawrence public schools, labor certificates were issued during the calendar year 1911 to 1,401 persons 14 and under 16 years of age, and to 4,425 persons 16 and under 21 years of age. Of the 4,425 persons 16 and under 21 years of age to whom labor certificates were issued 3,371 were literate and 1,054 were illiterate.

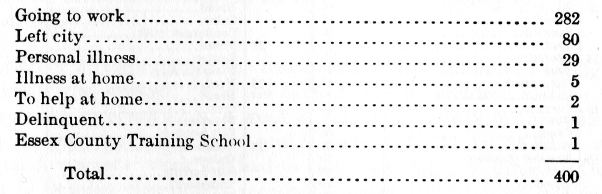

During 1911, 400 pupils withdrew from the grammar grades of the Lawrence public schools. Seventy per cent of these pupils left school for the purpose of going to work. The causes assigned for withdrawal were:

Of those withdrawing from school, 149, or 37.3 per cent, left the sixth grade; 153, or 38.3 per cent, left the seventh grade; and 89, or 22.3 per cent, left the eighth grade.

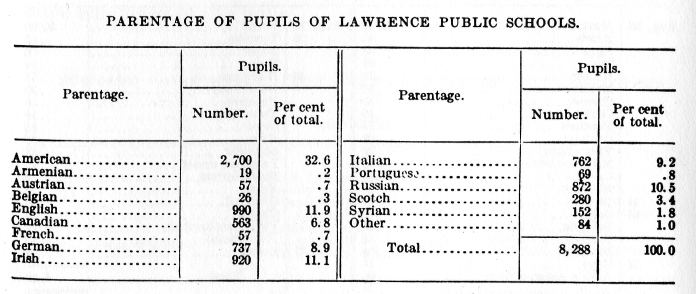

The report of the Lawrence school committee for 1909 includes a table showing the parentage of public-school pupils, as follows:

Thirty-two and six-tenths per cent of the pupils were of American parentage and 67.4 per cent were of foreign parentage.

The same report shows that one pupil out of five was born outside the United States and that three pupils out of five were born in Lawrence. The birthplace of the pupils was as follows:

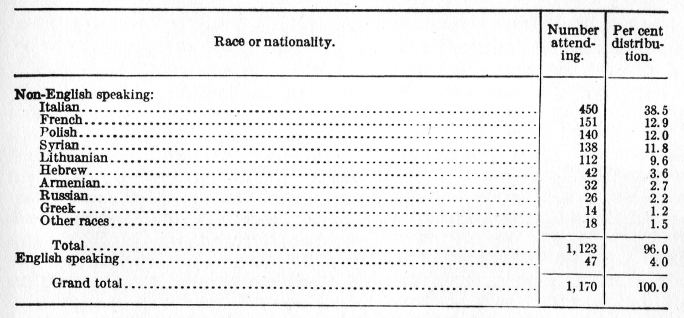

The nationality of those attending the evening elementary public schools in December, 1911, as reported by the superintendent ofschools, was as follows:

Of the 1,170 attending the elementary evening schools, 38.5 per cent were Italians, and a total of 96 per cent were of non-Englishspeaking races.

A report recently submitted to the Lawrence superintendent of schools by the head master gives the nationality of high-school graduates, as determined by birthplace of parents, as follows:

United States, 54 per cent; Ireland, 17 per cent; England, 9 per cent; Canada, 5 per cent; Germany, 5 per cent; Russia, 4 per cent; Scotland, 3 per cent; Italy, Austria, Syria, Armenia, and Egypt, each less than 1 per cent.

The total population of Lawrence, according to the United States census of 1910, was 85,892, and of that number, 73,928, or 86 per cent, were either of foreign birth or of foreign parentage and 11,964, or 14 per cent, were of native parentage.(1) Of the total population, 51.8 per cent were native born and 48.2 per cent were foreign born. Of the 41,375 foreign-born persons, 7,696 were born in Canada (French) ; 6,693 in Italy; 5,943 in Ireland; 5,659 in England; and 4,352 in Russia.

The general death rate in Lawrence per 1,000 population of all ages in 1910 was 17.7. From the reports of the United States Census Office it is possible to compare Lawrence with 34 other cities. The death rate in Lawrence was lower than the death rate in 6 of the 34 cities, exactly the same as in 2 other cities, and higher than in 26 other cities included in the comparison. The cities which had a higher general death rate than Lawrence were Lowell, Mass., 19.7; Washington, D. C., 19.6; Portland, Me., 18.8; New Bedford, Mass., 18.6; Fall River, Mass., 18.4; and Pittsburgh, Pa., 17.9. Three of these six cities which had a higher death rate are distinctly textile cities, and one of the six is Washington with a large Negro population.

The infant mortality in Lawrence, as in other textile cities, is very high. This high infant mortality is a marked characteristic of most of the large, distinctly textile cities, both in the United States and in England. In 1909. the last year for which final figures are available, the reports of the United States Census Office show that for every 1,000 births in Lawrence there were 17,2 deaths of infants under 1 year of age. It is possible to compare Lawrence in this respect with 34 other cities. The infant death rate in Lawrence was lower than in 6 other cities and higher than in 28 other cities included in the comparison. The cities which showed a higher infant death rate than Lawrence were Manchester, N. II., 263; Holyoke, Mass., 231; Fall River, Mass., 186; Lowell, Mass., 185; Detroit., Mich., 176.; and Pawtucket, R. I., 173. All of these, with the exception of Holyoke, Mass., and Detroit, Mich., are distinctly textile cities. It must be remembered, however, that a comparison of infant death rates between cities of the United States can not much more than suggest the true situation....

(1) The census does not report birthplace of parents of Negroes and the 265 native-born Negroes in Lawrence have In this statement been included with the 11,964 of native parentage.