![]()

Write us!

[email protected]

No End to the Growing Settlements Insult

By Amira Hass

The news reader on the Voice of Palestine called the movement of IDF forces in the Gaza Strip a “withdrawal,” even though Omar Asour, commander of the National Security Forces, had told him it was merely the opening of the road to Palestinian traffic at four points along the highway that had been sealed off for two years.

Israelis were reminded of the spring of 1994, when uniformed Palestinians first took up positions in the area as Israeli forces moved out of the cities and camps to the margins of the Gaza Strip. Back then, IDF forces remained in about 20 percent of Gaza Strip territory, in fortified positions. This is the same territory that is designated for the expansion of the Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip—20 percent of the territory for 0.5 percent of the Strip’s residents.

This was the justice of the “withdrawal” of 1994 that was called “the peace process.” Before 2000 there was talk that it “wasn’t logical” to leave the settlements, especially the isolated ones, in the most densely populated area of the world.

All the talk was hot air, and settlers continued to dictate how the Palestinians would live—where a water pipe would not be, where a refugee camp would not expand, where cars would not drive and where a sewage treatment plant would not be built.

Now the talk is mainly about quiet and respite. Israelis yearn for a long respite from suicide terrorism inside the Green Line and the firing of Qassam rockets, a lull in the anxiety about sons and daughters serving in the territories.

Palestinians yearn for a lull in shooting at anyone found walking among the destroyed houses of Khan Yunis and Rafah or on the land that has been cleared along the edges of the orchards. They want a break from tank invasions of residential neighborhoods, from missiles fired at cars on bustling city streets. And of course, they yearn for the resumption of some sort of normality with the opening of the road that runs the length of the Gaza Strip.

People will get to work and school on time, raw materials will be delivered to construction sites. Palestinian Authority officials are hoping these immediate improvements will be an important factor in ensuring its control of various military groups.

Nevertheless, the Israeli defense establishment is skeptical about the chances of success. They know why. The army is well aware that for the Palestinians in the West Bank to feel a change as well the army will have to remove all roadblocks and barricades between villages and cities, and rescind all traffic restrictions. These are intended to ensure the well-being of Israeli citizens living in the West Bank settlements, which have proliferated in the past ten years. In the meantime, it all seems a near-fantasy.

Will the Kalandiya roadblock be dismantled, will the barbed-wire fences around the villages south of Ramallah be removed? Will the fences that shut in Kalkilya, Tul Karm and Nablus be moved to nearby IDF bases? Will Palestinians be permitted to drive on the highways, the “bypasses?”

Let’s assume that the limited freedom of movement as it existed in 2000 is restored, and the Palestinian Authority succeeds in preventing the military groups from violating the cease-fire. Then what? Does anyone in Israel expect the Palestinians to be so grateful for having been permitted to leave their confined quarters that they won’t see what is happening before their very eyes?

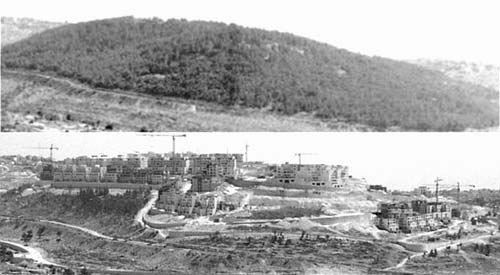

What is happening before their very eyes is the non-stop expansion of the settlements. Settlements are the unlawful transfer of an occupying population to occupied territory; they are the cynical theft of land reserves vital for the Palestinian cities and villages; they are the denial of territorial contiguity and the potential to develop; they are the wresting of control of irreplaceable water resources; they are control of roads. They are all that, and more.

The settlements embody all of the perceptions of Israeli lordliness that have developed over the years on both sides of the Green Line. It is an axiom now that “state lands” are only for Jews; that Palestinians need less land and water per head than Jews; that they do not deserve or require the same infrastructure or conveniences as Jews (see East Jerusalem and Galilee villages); that Palestinians live here because we allow them, not because it is their right.

The settlements provoke that deep sense of insult felt by anyone whom the regime decides is worthy of far, far less than his fellow man.

That is the discrimination practiced every day, and every minute of every day. It is an alienating, burning insult, the same one familiar to the blacks of South Africa, the blacks of the United States, and the Jews of Eastern Europe.

The Israeli defense establishment knows well why it is skeptical about the success of the cease-fire agreement. Because when the Palestinians, like every other human being, can again drive a distance of 10 kilometers in seven minutes rather than five days, they will also once again see on their territory the flourishing settlements and the Israeli army protecting them.

They will discover an Israeli political establishment that may at most discuss the outposts, but does not see the insult, the end-result of discrimination and thievery, and for whom Ariel, Alei Sinai, Ma’ale Adumim, Efrat and Nokdim are as natural and eternal as Tel Aviv and Raanana.

—Ha’aetz, July 2, 2003

Write us

[email protected]