![]()

Write us!

[email protected]

How Class Struggle Policy Guided the 1934 Teamsters Strike to Victory

Excerpts from Teamster Power By Farrell Dobbs

About the Author

Farrell Dobbs (1907-1983) joined the Communist League of America (the predecessor of the Socialist Workers Party) in 1934 while working in a Minneapolis coal yard. A rank-and-file leader of the 1934 Teamsters strikes and organizing drive, he was subsequently elected secretary-treasurer of Local 574 (later 544). In the late 1930s he was a central leader of the eleven-state over-the-road campaign that organized tens of thousands of workers in the trucking industry. In 1939 he was appointed general organizer of the Teamsters international. He resigned the post in 1940 to become SWP national labor secretary.

In 1941 Dobbs was indicted and convicted with seventeen other leaders of Local 544 and of the SWP under the thought control Smith Act for their opposition to the imperialist aims of the U.S. government in World War II. He spent twelve months in federal prison in 1944-45.

Dobbs served as editor of the Militant from 1943 to 1948. He was SWP national chairman from 1949 to 1953, and national secretary from 1953 to 1972. He was the party’s candidate for president in 1948, 1952, 1956 and 1960, using these campaigns to actively oppose the Korean and Vietnam Wars, the anticommunist witch-hunt, and to support the civil rights movement and the Cuban revolution.

In addition to his four-volume series on the Teamster battles of the 1930s: Teamster Rebellion, Teamster Power, Teamster Politics, Teamsters Bureaucracy. He is the author of the two-volume Revolutionary Continuity: Marxist Leadership in the U.S. Other works include The Structure and Organizational Principles of the Party, Counter-Mobilization: A Strategy to fight Racist and Fascist Attacks, and Selected Articles on the Labor Movement.1

• • •

(The following is his introduction and the first three chapters of Teamster Power, the second in Farrell Dobbs’s four volume series.2)

Introduction

The Teamsters union is the largest and probably the most powerful labor organization in the United States. How did it acquire that power? That is the central theme of this book.

The rise of the truck drivers began in the early 1930s. During 1934 workers across the country were stirred by a series of dramatic strikes in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This struggle drew nationwide attention because of its unique features, even though only a single local union was involved. The union was General Drivers Local 574 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, an American Federation of Labor affiliate.

In a previous book (Teamster Rebellion, Monad Press, 1972.) I have written an extensive account of the 1934 Minneapolis strikes. The following synopsis of the story is intended simply to acquaint the reader with the background against which events described in the present volume were to unfold.

Like other AFL units, Local 574 had long been characterized by conservative policies and an obsolete craft union structure embracing few members. By 1934, however, it was drawing broad layers of workers into a militant fight against the general trucking employers of the city. The change resulted from an internal transformation the union was undergoing during the heat of battle. A new, militant leadership was gradually gaining control and proving its competence in the eyes of rank-and-file members who wanted to use the union’s power in defense of their class interests.

Throughout the country labor militancy was on the rise under the pressures of severe economic depression. Millions upon millions were unemployed nationally. Workers lucky enough to have jobs had to get by as best they could on what were usually starvation wages. In Minneapolis, trucking companies paid as little as ten dollars and rarely above eighteen dollars for a work week ranging from fifty-four to ninety hours. It was not unusual for employed workers to need supplementary public assistance in order to support a family. Under these conditions the workers strongly desired a change for the better and they were ready to fight to bring it about

Politically this mood was expressed in Minnesota through growing support to the Farmer-Labor Party, a statewide movement based upon an alliance of trade unions and farmers’ organizations. In national politics the FLP tended to support the “New Deal” policies of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Within the state, however, it contended for public office against both the Democrats and Republicans. Its political strength was reflected in the election in 1930 and again in 1932 of Floyd B. Olson, the FLP candidate for governor.

Although Olson sought to project a pro-labor image, his basic objective was to advance his personal political career. For that reason he acted in a way calculated to assure the ruling class that he could be trusted to follow capitalist ground rules in exercising governmental authority. As a result, his performance in public office fell far short of the hopes and expectations of the working people who had elected him.

Parallel with their political support to the FLP, the workers were ready to join trade unions to fight for better wages and job conditions. At hand for the purpose in Minneapolis was only a small AFL movement consisting of a few local unions, which were little more than skeleton organizations. All were craft formations, restricted essentially to skilled or semiskilled workers.

A conservative officialdom sat astride this setup, seeking to win favor among the bosses through “statesmanlike” collaboration with them. This centered on efforts to create special job opportunities for relatively privileged categories of labor. Toward that end a few companies had been coaxed into hiring only AFL members; in return these firms were promised the patronage of organized labor as “fair” employers. Meanwhile, the needs of the bulk of the city’s workers were ignored.

The AFL’s “statesmanlike” approach was coldly received by the main sections of the ruling class. Anti-union policies were rigorously pushed by the major employer organization, the Citizens Alliance, which was dominated by the wealthiest, most powerful local capitalists. Faced with such strong opposition, the craft unions had been able to induce few companies to deal with them. This not only left them weak in numbers; they were more or less impotent, as shown by the fact that not a single strike had been won in the city for many years.

The conservative AFL officials had neither the desire nor the capacity to reverse this situation by organizing a militant struggle against the bosses. Instead they looked to Governor Olson for leadership in a “safe and sane” course intended to gradually strengthen the trade union movement with the cooperation of “fair” employers.

In that setting, a plan of action was developed by members of the Communist League of America (the organizational form of the Trotskyist movement at that time). They aimed to provide the fighting leadership needed and wanted by workers in the trucking industry. First, however, they had to battle their way into Local 574, which had jurisdiction over the coal yards in which they were employed. Steps could then be taken to convert the union into an instrument capable of serving the workers’ needs. Policies based on revolutionary class consciousness could be introduced. Rank-and-file militancy could be channeled into a showdown fight with the trucking employers. Conservative union officials who failed to meet the test of battle would begin to lose influence over the membership; and the Trotskyist militants could gradually develop and consolidate their role as the real leaders of the local.

Hundreds of unorganized workers in the coal industry were ready for unionization. Yet they were not welcomed into Local 574 because the business agent wanted to protect a little job trust he had set up through a closed shop contract with one coal firm. To cope with this problem the Trotskyists formed a voluntary organizing committee in the open-shop coal yards, the object being to mobilize mass pressure for admission into the union.

Support for that objective soon developed within Local 574’s executive board. A minority of the board favored the idea of broadening the union membership and waging a struggle for union recognition throughout the industry. After a time the executive board was forced to reverse its exclusionist policy. An official union campaign was then launched throughout the coal industry and before long the yards were quite solidly organized.

Demands for a working agreement were drawn up for submission to the coal employers. They refused to negotiate and the industry was struck in February 1934. The strike had several characteristics which were new to the Minneapolis labor movement. Instead of being half-heartedly conducted as a piecemeal action, it involved all the workers in all the coal yards. Picketing, which had been planned in advance, was conducted militantiy and effectively under the direct leadership of the voluntary organizing committee. In the process rank-and-file initiative and ingenuity were given free play with salutary results. On the first morning of the walkout the industry was tightly shut down and it was kept that way.

After a three-day tieup during a severe cold wave the employers made a settlement with the union. Despite inept handling of the negotiations by the official leadership, Local 574 had scored a victory. Union recognition—the key issue of the strike—was extended indirectly in the form of an employer stipulation with the Labor Board, a governmental agency set up by Roosevelt. Signing of the stipulation was made contingent upon the outcome of a representation election conducted by the Board, which the union won. Gains were also registered concerning wages and job conditions.

Most important of all, it had been shown that a strike could be won. That imbued workers throughout the general trucking industry with a new sense of hope in the union. The stage was thus set for a wider and deeper struggle.

By this time the voluntary organizing committee had gained enough support in the union’s expanded ranks to force through a decision giving it official status. With the help of sympathizers on Local 574’s executive board, the Trotskyist-led committee was able to set into motion a new, big organizing drive. Members were taken in from all sectors of the trucking industry, except in limited areas where other Teamster locals had jurisdiction over a specific sub-craft. Local 574 also passed beyond the IBT [International Brotherhood of Teamsters] norm of confining its membership more or less to truck drivers and helpers. Wherever possible workers whose jobs were in any way related to trucking—in shipping rooms, warehouses, etc.—were brought into the local. A shift was being made from the narrow craft form toward the broader industrial form of organization.

New members began flocking into the union by the hundreds. At a series of democratically conducted meetings the workers wrote their own ticket in shaping demands upon the employers. This helped to make the membership an integral part of the fight for a progressive union policy. It also gave fresh impetus to the organizing committee’s efforts to establish rank-and-file control over all the union’s affairs.

In the process, reinforcements came forward to strengthen the work of the organizing committee. Day by day the committee gained in leadership influence. Weaknesses stemming from incompetence within Local 574’s officialdom were thereby being offset as the union prepared for a showdown with the general trucking employers.

At mid-April the membership drive culminated in a mass rally held in a downtown theater. Public notice was given there of the union’s demands for a working agreement with the employers. The membership voted to strike if the demands were rejected. A large strike committee was elected to make the necessary plans for a walkout The committee was also empowered to set a deadline for an employer response to the union’s demands.

Parallel with these actions, steps were taken to put Governor Olson on record as sympathetic to the workers’ cause. He was reluctant to take such a public stand, hoping instead to maintain an “impartial” posture. As a Farmer-Laborite, however, he could not ignore the wishes of the labor movement, which was putting considerable pressure on him to speak up. So he sent a letter to Local 574’s mass rally counseling the workers to “band together for your own protection and welfare.” That didn’t make him a trustworthy ally. Yet it did make more difficult any attempt on his part to intervene against the union during the impending conflict.

All sectors of the AFL officialdom in the city were drawn into formal support of Local 574’s demands. This put them under obligation to help the local win its fight; it also served as a means to parry moves they were to make later on. Cooperative relations were developed with organizations of the unemployed in what proved to be a successful effort to mobilize jobless workers as fighting allies of the union. An auxiliary was formed among women in Local 574 families to draw them into active support of the struggle. Collaboration was also established with farmers in the area.

Meantime, the employers persisted in their refusal to deal with the union. They denounced the workers’ demands as a “Communist plot” to take over the city by imposing union control over all businesses. The Citizens Alliance announced steps to obtain cooperation from the mayor of Minneapolis and the city police in the event of a strike. The Alliance laid plans to reinforce the police with a large number of special deputies. Professional strikebreakers were also lined up for use against the union.

Local 574 in turn set up a big strike headquarters. It contained a commissary for feeding the strikers, an improvised hospital to care for union casualties, and a repair shop to service cars used by cruising picket squads. Plans for the picketing were carefully drawn, and the necessary command structure was devised. Convinced by such measures that the union meant business, the workers moved into action with high morale.

A strike against the general trucking employers began on May 16, 1934. Massive picket detachments quickly put a stop to all attempts at scab operations, demonstrating that Local 574 had become a power to be reckoned with. Then after four days of relative quiet the bosses opened a campaign of violence against the union. As they announced plans to begin operating trucks, police and hired thugs launched brutal attacks on peaceful pickets. The workers fought back with grim determination, doing the best they could barehanded.

After that the angry strikers equipped themselves with clubs to defend their picket lines. On two successive days they fought off assaults by large bodies of police and special deputies. Scores were injured on both sides and two deputies were killed during the bitter fighting in Minneapolis’s market-place area. The union came out victorious; not a single truck had been moved.

After the second day of fighting a truce was arranged. Negotiations finally began, with Governor Olson acting as an intermediary between the union and the employers. A settlement resulted in which the general trucking employers agreed to recognize the union in the indirect form of a Labor Board consent order. Olson assured the union that the recognition clause covered all its members, including inside workers on jobs related to trucking. Wage increases given by employers in an effort to prevent unionization were to remain intact; further pay hikes were to be decided by negotiation or arbitration after the strike. The settlement terms were accepted by the union membership and the victorious strikers returned to their jobs after a ten-day walkout.

Shortly thereafter the Citizens Alliance launched a campaign designed to repudiate the strike settlement. Trying to split the union, the employers said they would deal with it concerning only drivers, helpers, and platform workers; they flatly refused to do any bargaining concerning inside workers. At the same time they began a selective process of cutting wages and firing union members. Their actions could have only one meaning. They were deliberately forcing another strike, hoping that next time they could crush the union. That intent was made doubly clear when riot guns—murderous weapons using large scatter shot—were issued to the city police.

Faced with these provocations, Local 574 again girded for battle. La doing so it took an unprecedented step. A powerful new weapon was created through publication of an official union organ, The Organizer, which appeared daily during the ensuing conflict The paper served effectively to refute the bosses’ lies; it gave all workers the facts about the controversy and thereby helped greatly to mobilize support for the local.

One aspect of the labor mobilization took the form of a massive protest demonstration against the Citizens Alliance. Among the thousands who participated were members of other trade unions, unemployed workers, small farmers from the vicinity, and college students. All were united around the slogan: “Make Minneapolis a Union Town.”

At this point Daniel J. Tobin, general president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, launched a red-baiting attack on Local 574 through editorials in the official IBT magazine. He centered his fire on Trotskyist militants in the local. They were accused of “creating distrust, discontent, bloodshed and rebellion.” The Minneapolis labor movement was urged to “get busy and stifle such radicals.” Tobin’s diatribe was gleefully reprinted by the trucking bosses through a paid ad in the capitalist press, and they became even more adamant toward the union.

Tobin’s onslaught provoked an indignant reaction among rank-and-file unionists. They looked upon the Trotskyists as honest, competent, fighting leaders whose qualities had been proven in battle. Since the local’s internal affairs were now being conducted on a democratic basis, they felt that Tobin was actually hitting at the aims and aspirations of the union membership as a whole. This opinion was clearly demonstrated at a July 16 membership meeting where Local 574 decided by unanimous vote to resume the strike against the trucking companies. A passage in the strike call stated:

“We say plainly to D. J. Tobin: If you can’t act like a Union man, and help us, instead of helping the bosses, then at least have the decency to stand aside and let us fight our battle alone.”

A broad strike committee was again elected by the membership and empowered to make all executive decisions during the walkout. The official executive board was made an integral part of the larger body, although subordinate to it. In this way a highly effective leadership formation was created to guide the ranks in the coming showdown. The union could act as a solidly united force with a single purpose and a single policy.

As in May, hostilities began with an impressive demonstration of Local 574’s strength. Trucking operations were quickly brought to a halt. Then on the fourth day of the strike, July 20, 1934, a large body of police using riot guns fired without warning on a peacefully conducted mass picket line. When it was over, sixty-seven pickets and bystanders lay wounded and two of them died later from their injuries. Most of the victims of the police riot had been shot in the back.

Waves of anger over this outrage swept through the city’s working class. Sections of the middle class, horrified by the police violence, also gave support to the union. The strikers themselves, backed by a growing mass of sympathizers, continued their peaceful picketing in defiance of the murderous cops. Although a few trucks were moved under armed convoy, the tie-up remained basically effective. Riot guns had failed to break the strike; in fact it had gained new vigor.

In this tense situation federal mediators on the scene came forward with a proposal for settlement of the dispute. They called for recognition of the union wherever it could win a representation election conducted by the Labor Board. On the issue of hourly wages the union demanded 55 cents for truck drivers and 45 cents for helpers and inside workers; this was reduced by the mediators to 52 1/2 cents and 42 1/2 cents for the respective categories. Governor Olson then endorsed the proposal and called upon the union and the employers to accept it; if this were not done, he announced, he would declare martial law and impose a strike settlement on the mediators’ terms. In this difficult situation Local 574 decided it was advisable to accept the proposed settlement; however, the arrogant employers rejected it.

On July 26 Olson put the city under martial law and decreed that trucks could be operated only by firms which accepted the mediators’ proposal. Soon, however, military permits for general trucking operations were being issued so loosely that the strike was endangered. Local 574 reacted by preparing to resume mass picketing in defiance of the military. Olson thereupon ordered his troops to seize the strike headquarters and arrest the union leaders. With the help of conservative AFL officials he then tried to induce the seemingly headless union to call off the strike.

His scheme didn’t work. Militant picketing exploded upon the city, despite the presence of troops, and casualties among scab truck drivers mounted by the hour. Olson’s action brought swift condemnation from the membership of AFL unions and the ranks of the Farmer-Labor Party. He found himself compelled to release those Local 574 leaders his soldiers had managed to arrest and return the strike headquarters to the union; he also felt it necessary to tighten up on the issuance of military permits for scab trucking.

After that the controversy settled into a war of attrition. The employers tried unsuccessfully to get a court injunction against Olson so they could resume the use of police violence against the union. Then the federal mediators sought to induce Local 574 to accept a watered-down version of the terms they had proposed earlier for ending the strike. When that failed the bosses began to maneuver for a rigged Labor Board election in which scabs would be ruled the “eligible” employees. While all this was going on, Olson increased the granting of permits for scab trucking and he intensified military arrests of pickets.

By now the attrition was causing difficulties for Local 574. Things were getting rough for strikers whose families had fallen into dire economic need during the long conflict. Hard put itself in meeting strike expenses, the union could do little more than help them fight to get on public relief. As a result a few strikers were giving up the struggle and drifting back to work.

The wear and tear was not confined to the union alone. Employers, too, were feeling the effects of the lengthy struggle and they could not hold out indefinitely against the union. Matters had boiled down to a question of staying power, with both sides put to the test.

At this stage a new mediator arrived from Washington, D. C. He informed the strike leaders that he had convinced the head of the Citizens Alliance to call off the fight. At the union’s request he put in writing an assurance that the employers would accept his proposal for a settlement. The terms called for a Labor Board election to determine union recognition, with voting confined to employees on company payrolls as of the day the strike began. Union representation was to include inside workers at the wholesale market firms, and a decision on wages was to be made through arbitration.

On August 21, 1934, the union membership voted to accept the new settlement proposal, and the strike ended. In the Labor Board elections the union won bargaining rights for a majority of those employed in the general trucking industry. The arbitration award set hourly wages at 52 1/2 cents for truck drivers and 42 1/2 cents for helpers and inside workers; a year later each category was to be increased another 2 1/2 cents an hour.

Basic to the whole struggle had been the winning of union recognition. With that accomplished any lag on other matters would be only limited and temporary. Now firmly established in the industry, the union was in a position to make steady advances. On balance, the workers had won a sweeping victory and Local 574 had emerged from the struggle as a major power in the Minnesota labor movement.

1. Frame-Up Attempt

The triumph of General Drivers Local 574 over the trucking employers came as a body blow to the Citizens Alliance. For years this capitalist organization had exercised a virtual dictatorship over Minneapolis. It controlled the city government, including the police department from behind the scenes. Its banker wing kept a tight grip on the public purse strings, and its capitalist advertisers dictated the editorial policies of the daily newspapers. These powers were used to maintain an open-shop paradise in which working people were ruthlessly exploited for the private profit of the employing class.

When the Teamster organizing drive was opened in the spring of 1934, the Citizens Alliance had countered with a mobilization of its own. A special membership campaign was launched in an effort to develop a solid front of all employers in the city. Funds were raised for a war chest. An “advisory committee” was created to set policy for the trucking bosses. If any firm hesitated to challenge the growing Teamster power, threats of financial reprisal were used to keep it lined up in the Alliance wolf pack.

Under a propaganda cover branding the unionization drive a “Communist plot,” stool pigeons and agents provocateurs were planted in Local 574. Armed thugs and professional scabs were lined up for use against the workers. Although deputies mobilized during the May 1934 strike were certified by the authorities as “special police,” they were to all intents and purposes a private army of the bosses. They were recruited mainly by the Citizens Alliance, which also played a key role in arming them and setting up a special headquarters for their use.

During the July-August strike the police were ordered to make a murderous assault on peaceful pickets with riot guns. Coping with the angry public reaction to this outrage was viewed by the Alliance leaders as simply a tactical problem. Efforts were made to counteract public condemnation of the cold-blooded deed by having civic organizations of the capitalists issue statements praising the “bravery” of the cops. After committing such brutal acts, the bosses then had the gall to demand that workers accused of “violence” during the struggle be denied their jobs.

None of these strikebreaking devices availed. Local 574 won the fight; a strong union emerged in the trucking industry, and the employers had to deal with it This meant that the Citizens Alliance, already weakened by a major defeat, would now have to face a wider unionization trend among workers stimulated by the Teamster victory. The relationship of class forces had changed, and the Alliance leaders began to grope for new ways to combat the labor movement.

For openers they issued a fresh declaration of war, using Mayor A. G. Bainbridge as their mouthpiece. As the victorious strikers were returning to their jobs on August 22, 1934, the morning edition of the Minneapolis Tribune carried a statement by the mayor:

“Settlement of the strike should not be regarded as a victory for Communists. . . .” Bainbridge asserted.

I am serving notice here and now that our fight on Communism has just begun and I pledge myself to devote my time and effort to rid our city of those who defy law and order and who seek only to tear down our government. It will be a fight to the finish and I will not be satisfied until all those who foment unrest and hatred of legal authority are driven from our city. Let this serve as warning.

Pinpointing the central import of the mayor’s declaration, Local 574 replied to him and the employers in its own newspaper, The Organizer:

He [Bainbridge] means framing up every worker who fights for his rights. The Citizens Alliance, sore because they had to swallow the settlement, are planning to sic their bloodhound [Police Chief] Johannes onto some innocent individual workers and take it out of their hides. We warn all enemies of labor: Local 574 is going to take a hand in the fight against any kind of frame-up. Those who start this sort of business will be responsible for all the consequences.

A few weeks later another red-baiting attack on the labor movement was made obliquely. Early on the morning of October 16 vandals broke into the Workers Book Store, operated by the Communist Party in downtown Minneapolis. Furniture was overturned and smashed, pamphlets torn up and scattered on the floor. Scores of expensive volumes were stolen, as was a small amount of cash in the store. A crude sign left in the window proclaimed: “Modern Boston Tea Party. No Reds Wanted in Minneapolis.” The raiders then drove out Wayzata Boulevard a few miles and made a bonfire of the plundered literature. A second sign was left at the fire, saying: “First Warning to Communists.”

This act of vandalism was treated sympathetically in the daily papers. The Minneapolis Journal went so far as to attribute it to “irate citizens angered by the activity of revolutionary forces in Minneapolis.” Apparently it was thought that such a propaganda twist could build up public support of vigilante attacks on “reds.” Behind that notion lay the assumption that the unpopularity of the Communist Party would prevent significant protest from within the trade union movement. If that had proved to be the case, attacks of the kind could gradually have been extended to include other victims.

The Communist Party, which had by then become completely Stalinized, had itself been the author of its isolation from the mass movement. A combination of ultra-left policies and blind factionalism had caused the CP to Trotsky-bait the Local 574 strike leaders during the conflict with the employers. To the embattled workers this seemed much like the red-baiting carried on by the bosses, and the Stalinists came to be looked upon as enemies of the union. Aware of this sentiment, the Citizens Alliance policy makers were trying to exploit it to their advantage.

Once again, however, they had underestimated Local 574, which had been the main victim of the Stalinists’ unprincipled factionalism. Through a statement printed in The Organizer the union pointed out:

There are many workers in this city who are out of sympathy with the Communist Party. But it would be a shortsighted policy indeed to abstain for this reason from registering a vigorous protest against this vandalism. ... If they think they can get away with it, these vigilantes would like to terrorize every worker, every liberal minded person in the city. But they aren’t going to get away with it. ... If the police will not stop the plundering of the workers by these lawless vultures, the workers will.

On the heels of the vigilante episode a new plot was cooked up, this time directly against Local 574. It stemmed from the death of a special deputy, C. Arthur Lyman, during the May 1934 strike. Lyman was a wealthy lawyer who sat on the board of directors of the Citizens Alliance. Since his death the bosses had sought to picture him as a martyr “who fought for his country abroad [in World War I], and who knew how to fight and die for the same principles at home.” Now they had set out to find victims among the strikers who could be framed up on a charge of having killed Lyman; in the process they hoped to involve the strike leaders in an alleged conspiracy to commit murder. Their aim was not only to cripple the Teamster leadership; they plainly hoped to terrorize the entire AFL of the city and stem the developing trade union upsurge.

Word of the plot first reached Local 574 through an off-the-record tip from AFL officials sitting on the Hennepin County grand jury. They had been put on the jury because of their posture as “labor statesmen.” Capitalism uses such types, wherever practical, to give labor token representation on public bodies. The aim is to create an impression that actions taken by these bodies have general working class approval.

It is a trick to entrap the trade unions in the mechanisms of capitalist rule so as to deceive workers about the antilabor character of governmental policies. The device is further intended to compromise the conservative wing of organized labor and use it to hamper working class efforts to fight off capitalist attacks.

In the Lyman case the grand jury had learned that murder charges were in preparation against Emanuel (Happy) Holstein, a Local 574 member who had served on the strike committee. Right then and there the union officials on the jury should have openly denounced the plot. Apparently feeling that such action would tarnish their image as “statesmen,” they failed to do so. They did at least quietly inform Local 574 of what was in the wind, and that helped a good deal. The union was able to begin preparations to meet the impending attack.

Our informants also reported that the county prosecutor was floundering in uncertainty about the presentation of “evidence” against Holstein. His problem was understandable. Many strikers had doubtlessly wondered whether Lyman was one of the deputies they personally faced during the heavy fighting that took place in the marketplace area in May. There were also a few boasts on the subject, especially in taverns after a few convivial rounds. Considered soberly, however, no one could really know who struck this particular deputy.

For one thing it is highly unlikely that anyone on the union side knew that Lyman was among the deputies until his death was reported later in the newspapers. Teamsters and Citizens Alliance directors traveled in separate social circles and were not apt to be personally known to one another. Moreover, with a mass of pickets engaged in heated combat against a large body of police and deputies, personal features could not serve as marks of identity. The strikers wore union buttons, the cops were in uniform, and the deputies had special police badges pinned onto their civilian clothing. These were—and had to be—the ready means of distinguishing friend from foe in the fast-moving battle; opponents were not singled out as individuals. In such a situation it was preposterous to allege that a particular striker had clubbed a specific deputy.

These obvious facts were brushed aside by the employers. They were determined to use Lyman’s death to pin a murder rap on the union by one means or another. So detectives were assigned to fabricate a case as best they could. When that had been done the county prosecutor was ordered into action. It was no doubt assumed that intensive propaganda could be used to paper over the big cracks in the “evidence.”

Holstein was arrested on November 3 and held without charges. Local 574 immediately appealed to the whole labor movement for support against the frame-up. The appeal received a quick response. A broad trade union defense committee was formed at a big meeting of AFL officials. Simultaneously the Citizens Alliance plot was denounced in Labor Review, official organ of the Central Labor Union, a body composed of delegates from all AFL unions in the city.

“Organized labor is in an ugly mood at the attempted framing of Happy Holstein,” the AFL paper declared.

Trade unionists have not forgotten how Henry Ness and John Belor, valiant members of Drivers 574, were slaughtered and more than 40 others shot in the back. That there has been no effort to apprehend or indict those big shot higher-ups responsible for giving the order for their slaying, while Happy Holstein, a humble worker, is being attempted to be framed, is convincing the workers more than ever that the so-called machinery of justice is the machinery of class justice and not of even-handed justice.

After about two weeks the defense committee obtained Holstein’s release from jail through habeas corpus proceedings. He was then quickly rearrested, this time on a formal charge of having killed Lyman. Bail was set at $10,000. Placing its property under bond for the purpose, the Milk Drivers Union put up the bail and Happy was again released. The attempt to frame him finally ended when the grand jury voted a “no-bill” for lack of evidence.

In the meantime, a second intended victim, Phillip Scott, had been arrested. He was a youth of nineteen who had been involved in the May strike. In preparing Phillip’s defense the union lawyers learned from his mother that he had a history of emotional difficulties. While at school he had been kept in a special class under a doctor’s care. Part of his emotional problem was a tendency to give answers calculated to satisfy anyone who questioned him.

Scott had been tricked into a drinking jag by a police detective. He was then thrown into jail, and a “confession” that he had clubbed Lyman to death was wormed out of him. On this basis the prosecutor designed a scenario intended to implicate the strike leadership. Phillip was put through the ordeal of a sensational trial, and in the end he was acquitted. With that the whole frame-up attempt fizzled out.

Having suffered yet another defeat, the bosses decided to lie back for the time being and watch for a new chance to throw a rabbit punch at the union.

2. Leadership Showdown

While fighting off the attempt to frame it on murder charges, Local 574 was also preparing to go forward in the general struggle against the trucking employers. An editorial in The Organizer set the tone for this perspective. After summing up gains made through the victorious strike struggles, the editorial added:

A closer bond has been welded . . . [among] the men who produce for the profit of those who exploit them. As this bond grows closer, the degree of exploitation will lessen. The immediate task of the union is to consolidate its positions, gain new strength and prepare for the next step. . . . BUILD A BIGGER AND BETTER UNION! (Emphasis in original.)

To implement these objectives it was necessary to resolve contradictions existing within Local 574’s officialdom. Incompetents holding union office had to be removed. That could now be accomplished, thanks to the groundwork that had already been done. The Communist League had undertaken its campaign to win leadership recognition in the eyes of the union rank and file with clearly defined aims and carefully calculated tactics and timing.

From the outset the building of a broad left wing in the local was rooted in the programmatic concepts essential to a policy of militant struggle against the employers. Although this perspective entailed an ultimate clash with conservative union officials, their removal from office was not projected at the start as an immediate aim. That could have given the mistaken impression that the Trotskyist militants were interested primarily in winning union posts. To avoid such a misconception a flanking tactic was developed. Instead of calling for a quick formal change in the local’s leadership, the incumbent officials were pressed to alter their policies to meet the workers’ needs.

A program was advanced for the building of a strong organization capable of using its full power on behalf of all workers in the trucking industry. This outlook was counter-posed to the then official policy of creating special opportunities for a relatively privileged few. The left-wing perspective got a widespread welcome from the workers. They were ready to mobilize and launch a fight to establish the union throughout the industry. It followed that the momentum developed through such a struggle would lead toward an ultimate showdown over the leadership question.

Initially the left wing had taken form around the voluntary organizing committee in the open-shop coal yards. The committee functioned both as a caucus of militant workers and as a union-building instrument. An unofficial, but nonetheless real, leadership component had thus come into being among a growing body of workers who had yet to fight their way into the union.

The main obstacle to full unionization of the coal industry was a clique organized by Cliff Hall, an apprentice bureaucrat with strong yearnings to win recognition as a “labor statesman.” A member of the Milk Drivers Union, he had been hired by the executive board of Local 574 to serve as the local’s business agent. He sat on the board as an ex-officio member and exercised control over a majority of that body.

A minority of two among the seven board members stood opposed to Hall. They were William S. Brown, the union president, and George Frosig, the vice president; both sympathized with the concept of building a bigger and stronger organization. With the help of mass pressure mobilized by the voluntary organizing committee. Brown and Frosig forced through a reversal in policy that brought the coal workers into the union.

During the ensuing coal strike the Hall clique was able to maintain official control. Yet with Brown’s cooperation, as president of the local, the growing left wing inside the union could exert sufficient influence to make the picketing effective. This assured a partial union victory, despite bungled negotiation of settlement terms. This success, along with the general unionization campaign that followed, brought internal union developments to a new and higher plane. A situation of dual leadership authority began to take form.

The victorious coal workers had become a major component of the local. This strength was used to force through a decision upgrading the voluntary organizing committee to the status of an official union body. Workers pouring into the local from other sections of the trucking industry tended to emulate the veterans of the coal strike in looking to the now-official organizing committee for guidance. As a result the left wing gained steadily in size and influence.

Tactics inside the union on the leadership question were readjusted accordingly. On some matters the organizing committee simply by-passed the executive board; where this was not possible or advisable, it now had the strength to force the board into line on important issues. In every case, however, care was taken not to precipitate a premature leadership showdown over secondary matters. All tactical measures were shaped to conform with strategic objectives in the fight against the bosses.

When the May walkout took place a democratically elected strike committee exercised considerable power. This marked a further advance toward the left wing’s aim of establishing rank-and-file control over all union affairs, even though the executive board’s authority formally took priority over that of the strike committee.

After the strike another step was taken that intensified the development of dual leadership authority. Five left-wing leaders were officially added to the union’s organizational staff. They were Grant, Miles, and V. R. (Ray) Dunne, Carl Skoglund and myself—all members of the Communist League. These five plus Bill Brown, the union president, were looked upon by most rank and filers as the real central leadership of the union.

When the bosses forced another strike upon the workers in July, Local 574 entered the most critical phase of the conflict. It had become imperative that all union matters be competently handled: policy decisions, picketing, negotiations—everything. Fortunately the local’s internal situation had by then progressed to a point where the required measures could be taken.

The union elected a big strike committee, which was genuinely representative of the rank and file. This committee was given full executive authority in the strike, its powers explicitly superseding those of the executive board; the latter body was simply incorporated temporarily into the broad committee. This way the formal authority of incompetents on the executive board could be bypassed; this step minimized the danger of trouble from that quarter. With solid backing from the membership, the left wing had asserted full leadership responsibility for the duration of the struggle.

After the walkout ended, the strike committee was dissolved. Formal authority reverted back to the executive board where Hall still controlled a narrow majority. Hoping to profit from post-strike weariness in the ranks, he launched a red-baiting attack on the Trotskyist militants as a cover for disruptive activities inside the organization. Encouragement from other conservative AFL officials emboldened * the Hall clique; moreover they were obviously counting on help from Tobin, head of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, who was in a position to put strong pressure on the local.

This situation could not be allowed to fester. Decisive action was required in the form of an open showdown over the leadership question. Having already gotten a bellyful of Hall and his kind, the union membership was ready for the step.

A decision was forced through to schedule a new election of union officers. Brown was reelected president of the local and Frosig was returned to the vice presidency, both having been on the progressive side all the way. An incumbent trustee, Moe Hork, who had broken off his earlier collaboration with Hall and performed well during the strike, was also reelected. The remaining posts were won by Trotskyist militants: Grant Dunne, recording secretary; F. Dobbs, secretary-treasurer; Ray Dunne and Harry DeBoer, trustees.

Neither Miles Dunne nor Carl Skoglund, who had been among the central leaders of the strikes, ran for office. Miles had been assigned to help a Teamster local in Fargo, North Dakota. Carl had a citizenship problem which made it inadvisable for him to be a candidate at that time.

Under IBT procedures the seven officers who had been elected constituted the executive board of the local. As its first official act the new board summarily fired Hall. Since his IBT membership was in the Milk Drivers Union, Hall’s dismissal as business agent removed him entirely from the Local 574 scene. With the general housecleaning thus completed, the local was able to present a solid front against the bosses. Its power could be fully mobilized to defend and advance the workers’ interests; and at the head of the struggle would stand battle-tested militants who were united around a common program.

The new, homogeneous leadership functioned as a team. No one strutted around as a star performer or tried to be a dictator. Genuinely collective effort prevailed, within a division of labor designed according to the union’s needs, and the contributions of each individual were valued. Measures were initiated to gradually broaden the leadership team by educating outstanding militants in the ranks. In this way an expanding formation of secondary leaders was built up; they in turn helped to knit close relations between the leadership and the membership. Out of this process came a oneness which enabled the union to go forward as an effective combat force.

Traditional AFL “business agent” concepts were scrapped, as were other bureaucratic notions about “running” a union instead of leading it. The executive board members acted collectively as the central leadership of the local. In that capacity they did not presume to hand down orders to the rank and file; they gave overall guidance to the work of protecting and strengthening the organization, making executive decisions as needed to fulfill that responsibility.

A staff of full-time organizers was set up, composed of union officers and members who had played outstanding roles in the strikes. Their tasks in the main were to settle job grievances, recruit new members, handle negotiations with employers, and play a leading role in any walkouts that were called. Across an eighteen-month period the staff was built up to fourteen members. Included were Ray, Miles, and Grant Dunne, Carl Skoglund, Bill Brown, Harry DeBoer, George Frosig, Ray Rainbolt, Kelly Postal, Jack Maloney, Emil Hansen, Clarence Hamel, Happy Holstein. I was assigned to function as staff director.

On the question of staff wages the union leadership junked the outrageous bureaucratic practice of conniving to draw salaries comparable to those received by corporation executives. Staff pay was supposed to be twenty-six dollars a week, the going wage for truck drivers at the time; as new wage increases were won for the workers, the staff would then get a similar raise. For an extended period, however, the staff received at most twenty dollars a week, sometimes less. That resulted from money problems confronting the local in the aftermath of the long struggle against the bosses. In grappling with these problems the staff sought to lead by example, subordinating personal needs to union requirements at that difficult time. In various ways of their own, the union members reacted to the example by responding in kind.

Whether an elected officer or an apprentice organizer, all on the union staff got the same pay. None had to be hired in order to serve the union; they would do that in any case as best they could. It was a matter of making it possible for a given number of individuals to devote their entire time to organizational work. On that premise maximum effort was expected from each person; any variations in the services rendered would then result simply from differences in individual experience and ability.

Neither union post nor individual talent had any bearing on the rate of pay. All staff members shared common subsistence problems and all received comparable wages, special adjustments being made only where a given individual had exceptional family responsibilities. In this, as in every other respect, there was only one class of citizenship in the local; it was shared equally by elected officers, full-time organizers, and rank-and-file members.

To round out the organizational machinery a job steward system was established. Union members at each company selected a representative to fill the post. As would be expected, those chosen as stewards had played prominent roles during the strikes. In effect, the broad strike committee was being transformed into a permanent union body with vital functions.

As direct union representatives on the job, it was the stewards’ duty to defend the rights of union members; to see that working agreements with the employers were enforced; to bring all workers on the job into the union; and to insist that they keep themselves in good standing. Regular meetings of the steward body were held, with the union staff participating in the discussions. These sessions became a key part of the organizational mechanism because of the vital functions performed by the stewards. They were to a large extent the eyes, ears, and nerve center of the union.

Provisions for a closed-shop contract, entailing compulsory union membership and dues payments, had been included among Local 574’s prestrike demands. This had been done at the insistence of Hall, who took the bureaucratic view on the question. That view sees the closed shop as a liberating instrument—for the bureaucrats, that is, not the workers. It enables officials sitting on top of a union to more or less freely ignore or go against the wishes of the rank and file. No matter how dissatisfied this may make the workers, dues must still be paid, and the bureaucrats continue to have a union treasury at their disposal.

A different view on the same question arises when workers are inspired by the union. They develop a healthy resentment against freeloaders on the job and look for ways of forcing them at least to contribute financially to the cause. That leads them to favor putting a clause in the agreement with the employer making payment of union dues compulsory. It follows from this that the closed-shop question is a tactical matter; one to be decided according to the total complex of factors in a given situation.

In Local 574’s case. Hall’s closed-shop demand was unrealistic; as events proved, it took a bitter struggle to win even the simplest form of union recognition. Yet with other, more complex factors in the internal union situation taking precedence, it was unwise to oppose Hall on the closed-shop matter. The issue was simply allowed to die a natural death during the fight with the bosses.

Now that the employers had been defeated and the local was firmly rooted in the trucking industry, the rank and file strongly favored compulsory union membership and dues payments. The problem was one of finding a way to apply the desired compulsion. Key steps toward that end had been taken in setting up the union staff and organizing the steward system. A further measure was then devised which came to be known as a “fink drive.”

Drives of this kind took place periodically. They were conducted by mobilizing the entire union staff and a substantial number of volunteer union activists who took off from work for the purpose. A dragnet was formed to comb the city. Trucks were stopped on the streets; a check was made of loading docks, shipping rooms, warehouses, etc.; back dues were collected from delinquent members, and new members were signed up. Through this overall combination of measures the local was able to maintain a rather tight union shop.

Parallel with these steps, methods were devised to broaden the local’s scope and streamline its structure. Full advantage was taken of the “general” charter it had received from the IBT. Workers whose jobs were by any plausible definition related to trucking were signed up as Local 574 reached into every quarter of the industry not explicitly covered by another IBT charter.

In its internal functioning the local held general meetings twice monthly which were open to all union members; these gatherings dealt primarily with broad and fundamental problems. To cope with matters arising from the diversified nature of the trucking industry, sub-sections were set up to handle matters peculiar to one or another part of the industry. This allowed the workers in each particular section to make decisions about their own unique problems. At the same time they had the advantage in dealing with the employers of solid backing from the union as a whole. From time to time one of the sections would find it necessary to call a strike in its sphere of the industry. As it turned out these fights were won without need of reinforcement through a general walkout by the union membership. But power of that kind was always there to be used if required.

Care was taken in systematizing the union machinery to protect the democratic rights of the rank and file. Such concern, of course, came naturally from a leadership that strove consciously to involve the membership in every aspect of the local’s activity. There was complete freedom of expression for all views. Policy matters were presented by the leadership in a reasoned way, and full discussion was encouraged so as to reach a clear understanding about the union’s objectives. On all questions the general membership meeting had the final say; it was the supreme authority in the organization.

New by-laws were adopted by the local after they had been carefully thought out by the drafting committee and studied by the rank and file. Under the revised rules officers were elected for a one-year term. That procedure gave the membership a frequent opportunity to review their performance and decide whether they should be reelected or replaced. The election procedure began with nominations for office at a general membership meeting. A period of one month was then allowed for electioneering, during which opposition candidates were accorded equal rights with incumbents running for re-election. Voting then took place by secret ballot at the union hall, where polls were open for two days. The whole procedure was conducted by five election judges selected by the membership.

All in all, rank-and-file control over Local 574’s affairs, including democratic selection of the leadership, had become a living reality. This was the mainspring of its strength.

3. Class-Struggle Policy

With the change in official leadership, efforts to construct an ever-stronger left wing took new forms within the local. It was no longer a matter of building a broad caucus around a militant program in order to displace misleaders sitting on top of the organization. Conscious revolutionists were now at the helm, and they enjoyed harmonious relations with the rank and file. As matters now stood the union itself had become a left-wing formation in the local labor movement and in the IBT. Internal differentiations had been reduced essentially to varying degrees of class consciousness. From this it followed that the next major task was to make the general membership more aware of the laws of class struggle.

Workers who have no radical background enter the trade unions steeped in misconceptions and prejudices that the capitalist rulers have inculcated into them since childhood. This was wholly true of Local 574 members. They began to learn class lessons only in the course of struggle against the employers.

Their strike experiences had taught them a good deal. Notions that workers have anything in common with bosses were undermined by harsh reality. Illusions about the police being “protectors of the people” began to be dispelled. Eyes were opened to the role of the capitalist government, as revealed in its methods of rule through deception and brutality. At the same time the workers were gaining confidence in their class power, having emerged victorious from their organized confrontation with the employers.

To intensify the learning process already so well started, the union leadership now initiated an educational program. Study courses open to all members were organized. The curriculum included economics, labor history and politics, public speaking, strike strategy, and union structure and tactics.

Wherever practical, officers’ reports at membership meetings were given with a view toward making them instructive as well as factually informative. Articles of an educational nature were printed in the union paper. The themes varied from analysis of local problems to coverage of events and discussion of issues in the national and international labor movement

These endeavors stood in marked contrast to the policies of bureaucratic union officials. Bureaucrats don’t look upon the labor movement as a fighting instrument dedicated solely to the workers’ interests; they tend rather to view trade unions as a base upon which to build personal careers as “labor statesmen.”

Such ambitions cause them to seek collaborative relations with the ruling class. Toward that end the bureaucrats argue that, employers being the providers of jobs, labor and capital have common interests. They contend that exploiters of labor must make “fair” profits if they are to pay “fair” wages. Workers are told that they must take a “responsible” attitude so as to make the bosses feel that unions are a necessary part of their businesses. On every count the ruling class is given a big edge over the union rank and file.

In carrying out their class-collaborationist line, the union bureaucrats exercise tight control over negotiations with employers. They try to avoid strikes over working agreements if at all possible. When a walkout does take place, they usually leap at the first chance for a settlement.

Once a contract has been signed with an employer they consider all hostilities terminated. Membership attempts to take direct action where necessary to enforce the agreement are declared “unauthorized” and a violation of “solemn covenants.” In fact the bureaucrats often gang up with the bosses to victimize rebel workers.

Local 574’s leadership flatly repudiated the bankrupt line of the class collaborationists. There can be no such thing as an equitable class peace, the membership was taught. The law of the jungle prevails under capitalism. If the workers don’t fight as a class to defend their interests, the bosses will gouge them. Reflecting these concepts, the preamble to the new by-laws adopted by the local stated:

“The working class whose life depends on the sale of labor and the employing class who live upon the labor of others, confront each other on the industrial field contending for the wealth created by those who toil. The drive for profit dominates the bosses’ life. Low wages, long hours, the speed-up are weapons in the hands of the employer under the wage system. Striving always for a greater share of the wealth created by his labor, the worker must depend upon his organized strength. A militant policy backed by united action must be opposed to the program of the boss.

“The trade unions in the past have failed to fulfill their historic obligation. The masses of the workers are unorganized. The craft form has long been outmoded by gigantic capitalist expansion. Industrial unions are the order of the day.

“It is the natural right of all labor to own and enjoy the wealth created by it. Organized by industry and prepared for the grueling daily struggle is the way in which lasting gains can be won by the workers as a class.”

As these views set forth in the preamble affirm, there was no toying with reactionary ideas about stable class relations in the trucking industry. Stability was sought only for Local 574 itself, so that membership needs could better be served. Relations with the employers were shaped according to the realities of class struggle. The concepts involved are illustrated by the union’s approach to the question of working agreements with the trucking companies.

It was recognized that contracts between unions and employers serve only to codify the relationship of class forces at a given juncture. More precisely, they merely record promises wrung from employers. If a union is poorly led, the bosses will violate their promises, undermine the contract in daily practice, and put the workers on the defensive. Conversely, a properly led union will strive to enforce the contract to the letter. It will also undertake to pass beyond the formal terms of agreement to the extent this may be practical in order to establish preconditions for improved written provisions when the contract comes up for renewal. In every case, either the unions will press for greater improvement in the workers’ situation, or the employers will be able to concentrate on efforts to nullify gains the workers have made.

Another matter related to these basic considerations is the length of time working agreements are to remain in effect. Class-collaborationist union officials, who yearn for stable worker-employer relations, favor long term agreements. They want to keep the membership locked up in a given status-quo situation for the longest possible time. Militant union leaders, on the other hand, prefer relatively short term contracts, so that gains for the membership can be registered more frequently.

In Local 574’s case the general practice was to limit agreements to a period of one year. This applied both to the negotiation of renewal terms when the August 1934 strike settlement expired later on and to the signing of contracts with companies whose employees were newly organized.

On the question of making employers keep their promises, the handling of grievances becomes vital. Here again class-collaborationist policies entrap the workers. Union bureaucrats are quick to include a no-strike pledge in contract settlements and refer grievances to arbitration. The workers lose because arbitration boards are rigged against them, the “impartial” board members invariably being “neutral” on the employers’ side. Moreover, the bosses remain free to violate the working agreement at will, as grievances pile up behind the arbitration dam.

In a similar vein, conservative union officials are prone to make a general no-strike pledge when the capitalist government proclaims a “national emergency.” They do so by bureaucratic fiat, giving rank-and-file workers no voice in the decision. Such “labor statesmanship” amounts to proclaiming an overall “truce” between the workers and the bosses. Actually no truce results at all. The capitalists simply use their government to attack the trade union movement under the guise of a “national emergency”; and the workers, deprived in such a situation of their strike weapon, get it in the neck.

A development in the fall of 1934 involved this very issue. In the name of “national recovery,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked labor to forgo its right to strike. Concerning disputes with employers, he said, trade unions should accept decisions by government boards as final and binding. William Green, president of the AFL, was quick to second Roosevelt’s proposal and call upon the labor movement to put it into practice. Local 574 gave both Roosevelt and Green its answer through an editorial in The Organizer:

“Labor cannot and will not give up the strike weapon. Labor has not in the past received any real benefits from the governmental boards and constituted authorities. What Labor has received in union recognition, wage raises and betterment in conditions of work, has been won in spite of such boards. … The strike is the one weapon that the employers respect … Whether or not there is a period of industrial peace will depend upon the employers’ reply to our demands.” (Emphasis in original.)

It did not follow from this position that Local 574 called strikes lightly. There are always hardships involved for the workers in such struggles. If the union moved blithely from one walkout to the next, without careful regard of all factors in the situation, it could easily wear out its fighting forces. The important thing is that a union stand ready and able to take strike action when required. In fact there are occasions where readiness to use the strike weapon can make its employment unnecessary.

Retention of the unqualified right to strike and readiness to use the weapon were central to the local’s enforcement of the 1934 settlement with the trucking firms. Employer attempts to impose arbitration of workers’ grievances were brushed aside. There had to be full and immediate compliance with the settlement terms—or else.

In carrying out this policy the union leadership did not merely sit back waiting for an occasional member to file a grievance. All workers were urged to demand their full rights on the job, to protest any denial of these rights and to stand in solidarity with fellow workers who ran into difficulties. Toward that end, an unusual provision was included in the by-laws when they were revised. New members entering the union were required to assume the following obligation:

“I do solemnly and sincerely pledge my word and honor that I will bear true allegiance to Local 574 and to the entire organized labor movement. I will obey the rules and regulations of my union. I will demand my full rights on my job in accordance with the union agreement under which I am working. I will not scab on my fellow workers in any industry or trade, and in the event of a strike by my union or any bona fide union, I will do all in my power to bring victory to the striking workers.”

There was one important addition to the above obligation: when a meeting was called to take up grievances against the employer, the changed by-laws made compulsory the attendance of all union members working at the company involved.

Important though such provisions were, they served mainly as a means to educate the membership in basic union principles. Formal obligations and rules could not in themselves provide the dynamism needed to apply those principles in daily practice. For that purpose Local 574’s fighting qualities had to be demonstrated anew in the changed situation after the July-August strike was settled. An opportunity to do so was speedily provided by the trucking companies.

Resisting adjustment to the new union presence in the industry, the employers tried in various ways to proceed as though nothing much had changed. Grievances involving discrimination against union members began to pile up. Theoretically, under the terms of the August settlement, these matters were to be adjusted by Roosevelt’s Labor Board, but nothing was done by that body.

Notice was therefore served that failure of the Board to perform its agreed upon functions would lead to direct action by the union. The warning was ignored. A few companies were then struck—those guilty of the most flagrant violations—and they were compelled to settle all complaints. The whole industry got the message. After that only infrequent strike action was needed to enforce compliance with working agreements.

It was not only a matter of teaching the bosses a lesson. At the same time all union members received dramatic assurance that their grievances would get serious attention. Evidence was also given that the job stewards would be backed by the full union power. Unity of action was thus being forged between the executive board, organization staff, job stewards, and the rank and file to make the bosses toe the line.

The local was on the way to establishment of union control on the job. Moreover, it was to be the kind of control that always sought to help the workers and never to hurt them.

These progressive characteristics resulted from the class-struggle ideology that now predominated within Local 574. There were, of course, variations in the degree to which this ideology was grasped by different strata in the membership. Among the broadest layers class consciousness was developing only in the more elementary forms. There was an awakening realization of basic antagonisms in class interests between labor and capital. The need for working class unity was generally perceived, as was the necessity of using the union’s power in aggressive defense of labor’s interests.

A narrower but significant layer of the membership was learning political lessons from experiences in the class struggle. These workers were coming to understand some of the causes of class antagonisms between labor and capital. They were growing more perceptive about the class role of the bosses’ government The realization that class conflict under capitalism is an unending and complex process was permeating their consciousness.

Some of the more advanced workers gradually developed in their thinking to the point where they became receptive to revolutionary socialist ideas. As a result they were recruited by ones and twos into the Trotskyist party, then called the Communist League.

In the revolutionary party—which represents the highest form of class consciousness within the labor movement—these workers advanced further in their understanding of the class struggle. They learned the necessity of the working class and its allies orienting toward a fight for state power. It was brought home to them that none of their basic problems could be definitively solved until capitalism was abolished and society reorganized on an enlightened socialist basis. They also began to learn about the program, strategy, and tactics required to achieve that revolutionary goal.

It should be noted in passing that loyalty to a program does not always lead automatically to full acceptance of the organizational responsibilities involved. There are cases where organizational derelictions will occur on the part of otherwise loyal individuals. Yet they will remain capable of important contributions to the movement despite that weakness. An astute leadership will keep the latter factor in mind and endeavor to draw the given individuals into activity so far as possible. Two examples within Local 574 will illustrate the point: they concerned Bill Abar, a rank-and-file member, and Bill Brown, president of the local.

Abar was a one-man army on a picket line, but he showed little or no interest in routine union affairs. In a strike situation he was sure to be in the front row at membership meetings, eager for action. At other times, however, he was quite consistently absent from meetings and correspondingly delinquent in paying his union dues. Although these derelictions were regrettable, they were recognized as secondary in Abar’s case. The union staff used to take up a voluntary collection to make sure that his dues obligations were met This was done out of respect for his qualities as a fighter and his reliability when a strike was on.

Brown, on the other hand, was fully active in the union. His organizational shortcomings lay in a different quarter. He considered himself a loyal Trotskyist and, politically, he was. For his own reasons, however, he did not actually join the Trotskyist party and give direct organizational help in building it. While this implied, if considered formally, that he should be excluded from meetings of party members within Local 574, that was not done. He was invited to attend whenever important matters related to union policy were to be taken up.

There were several reasons for this procedure. As a loyal supporter of the party’s class-struggle policy within the union, Brown had earned the right to such respect and trust He, in turn, reciprocated by making useful contributions in discussions of policy matters. At the same time, such collective discussions broadened his own thinking beyond the ordinary, more limited framework of formal union deliberations. This enabled him to act more effectively in helping to carry out the aims of the union leadership.

Policy discussions among the Trotskyists in Local 574 were basic to their functioning as an organized fraction of the party. Within the fraction, party comrades had equal voice and vote; this applied whether they were rank-and-file members, job stewards, organizers, or elected officers of the union. The procedure flowed from their common objectives as politically conscious militants. All sought to advance class-struggle perspectives among the workers generally and to help implement these perspectives in action. As for the differences in formal union status, these related primarily to the manner in which individual comrades contributed to the united effort.

Fractions of the kind functioned as a subdivision of a general membership branch embracing all party comrades in the city. Included in the branch were workers from various unions, along with students and intellectuals. Through their collective relationship—focused around political activity and socialist education—all were helped to broaden and deepen their revolutionary consciousness. This process was aided by party literature distributed nationally, especially the Trotskyist weekly paper The Militant

Direct guidance and help from the party’s national leadership was always available to members engaged in class-struggle activities. This was richly demonstrated during the critical July-August stage of Local 574’s fight against the trucking bosses. Top leaders of the party came to Minneapolis to give on-the-spot aid to the embattled union. Their support included not only valuable political advice to the union leaders who were engaged in a complex struggle; they brought with them specialists to help in such vital matters as publishing The Organizer, mobilizing support among the unemployed, and handling legal problems.

Through its total efforts to reinforce the workers’ struggles, the party was steadily winning new members. Its gains within Local 574 were only part of the development The wider patterns of party growth were reflected in the statistics of the Minneapolis branch. In 1933 the branch had about forty members and close sympathizers; by the end of 1934 the figure had more than doubled to about 100.

Advances were also being made nationally, as symbolized by a particularly significant event. Late in 1934 the Communist League fused with the American Workers Party to establish a new organization called the Workers Party of the United States. The fusion was based on common acceptance of the essential Trotskyist program.

Within the AWP were revolutionaries who had led a strike of auto workers at the Electric Auto-Lite plant in Toledo, Ohio. Their struggle had paralleled the Minneapolis strikes in both militancy and national significance. Now these revolutionary workers’ leaders of Toledo and Minneapolis had come together in the same party. It was a good omen for the Trotskyist movement as it entered 1935 in the form of the Workers Party.

————————

1 “About the Author” appears in the first volume of Dobbs’s Teamster series; Teamster Rebellion, Pathfinder, New York, 1972

2 Teamster Power, by Farrell Dobbs, Monad Press, New York, 1973.

|

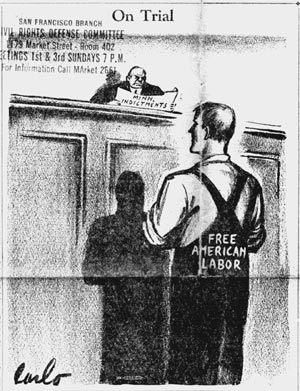

| The cover of the pamphlet On Trial published and distributed by the Civil Rights Defense Committee. In 1941, 29 leaders and organizers prominent in the success of Minneapolis Teamster Locals 574 and 544 were indicted by the U.S. government for their antiwar views. The Civil Rights Defense Committee was organized to provide legal defense, publicize the case and mobilize support from the American worker. During 1942 around 150 central labor bodies and local unions, speaking for over one million workers, passed resolutions protesting the violation of the constitutional rights of labor. |

Write us

[email protected]