First Published: The Call, Vol. 7, No. 33, August 28, 1978.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

This is the eighth in a series of articles by Call journalists who visited Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) in April. They were the first Americans to visit that country since its liberation in 1975.

* * *

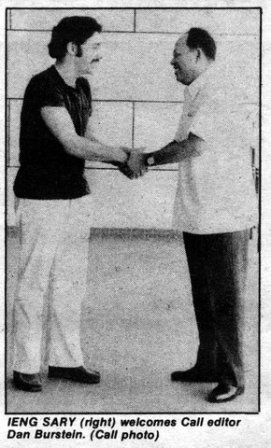

The high point of our visit to Kampuchea came the day before we were scheduled to leave. Ieng Sary, the Deputy Prime Minister in charge of foreign affairs, had agreed to give us an interview. He would brief us on the answers to numerous questions we had raised about the history of Kampuchea’s revolution and its present state of development.

When we arrived at the house where the meeting was to take place, Sary was outside waiting for us. Dispensing with all formality, he came over to our car, embracing each of us as we got out.

Sary’s warm and jovial manner belied the many bitter experiences he had lived through. Now 48 years old, Sary was one of the founders of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and had been a guerrilla fighter in the countryside between 1963 and 1970. From 1970 until the victory of the revolution in 1975, he had travelled the world as special envoy of the united front government, fighting to win support for Kampuchea’s liberation war in the international arena.

With a map of Kampuchea sprawled out in front of him and a cup of tea beside him, Sary began telling us the story of the Kampuchean revolution step-by-step, point-by-point. It would be midnight before he brought the story to a close, having patiently answered all our questions.

“In the days that you have been here,” Sary began, “we have learned a lot from you about the struggles of the American people and the revolutionary movement in your country. Today, we will share with you some of our experiences in our revolution. Your Party is young and your revolution is just unfolding. Although we are convinced that you will win victory, we also know that you face many of the same difficulties we did in the beginning of our struggle.

“Perhaps what I have to say will be of benefit to you. Of course, this is not a theory or a doctrine. These are just the experiences that we have had under the conditions of our country.”

After his introductory remarks, the Deputy Prime Minister plunged right into the history of the revolution, beginning with the mass upsurge that followed the defeat of the pro-Japanese puppet government in 1945.

With Japan defeated, the French colonialists who had ruled Kampuchea for generations made their comeback. The people bitterly hated the French colonialists, and struggle against them began to take place on many fronts.

Different forces wanted to fight the French, Sary said, and they all had different approaches. Within the nationalist movement (which was made up primarily of national capitalists, intellectuals, and petty-bourgeois elements), there was considerable sentiment for anti-colonial struggle. But it was not thorough-going. These forces would time and again make secret deals with the French.

The Indochina Communist Party also existed in Kampuchea at this time, but it was made up exclusively of Vietnamese cadres. It supported and led the armed struggle against the French.

There were also revolutionary organizations of Kampuchean people who began waging armed struggle as early as 1947. But no Marxist-Leninist leadership existed for this movement.

“The main task at this stage,” Sary said, “was to win our national independence from France.” But contradictions also developed between Kampuchean anti-imperialists and the Vietnamese in the Indochina Communist Party, even though the two movements were in solidarity.

As an example of these contradictions, Sary pointed out, “Vietnam trained its cadres at this time in the belief that the three countries of Indochina were really all one country and should have only one Party. We didn’t agree.”

Despite these contradictions, the anti-imperialist struggle continued to advance. Tens of thousands of Kampucheans died fighting the French imperialists in this period. Finally, the Geneva peace agreement was reached in 1954, supposedly guaranteeing independence for Kampuchea, Laos and Vietnam. In Kampuchea, Prince Sihanouk came to power after Geneva.

In the 1950s, many of the leading elements in the Kampuchean people’s liberation struggle began to study Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung Thought. They rejected the notion of “peaceful transition to socialism” put forward in Khrushchev’s 1956 speech. Their own experiences had shown them that without the armed struggle, the people could not be victorious.

Ieng Sary noted that there was sharp ideological struggle over this question. The Vietnamese leaders, he said, had opposed Khrushchev’s line about “peaceful transition” insofar as Vietnam was concerned and correctly insisted that armed struggle was necessary to liberate their country and establish socialism. But, said Sary, some leaders of the Vietnamese Workers Party simultaneously argued that armed struggle was not necessary in Kampuchea. They said that socialism could come about peacefully in Kampuchea because of the progressive, neutralist stand taken by Prince Sihanouk.

While recognizing many areas of potential unity with Sihanouk, the Kampuchean revolutionaries believed that to liberate the country from foreign domination once and for all, to do away with feudalism and capitalism and to establish a socialist system, an armed struggle would definitely be required. They believed that to fail to prepare for the armed struggle was to set the stage for slaughter.

Even while the issue of armed struggle was being debated, the Kampuchean people’s forces were facing heavy repression. Over 80% of the 4,000 cadres in the revolutionary movement that had fought the French were wiped out in the 1950s. Sary added that in 1958, the leader of this movement, who had been trained in Vietnam, actually went over to the side of the government. He betrayed the revolutionary forces and set up executions and assassinations of revolutionary leaders.

“After this betrayal,” said Sary, “we knew that we had to become more self-reliant, deepen our understanding of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tsetung Thought and found a communist party of our own to organize and lead the struggle.”

Preparations were undertaken by the growing circle of Kampuchean communists to develop a political program make a class analysis of Kampuchean society, and set the Party up organizationally.

“The repression was very intense at that time,” Sary recalled. “We had very little experience. We had no money. We went secretly to the Soviet embassy in Phnom Penh to ask for a loan of 10,000 riels (about $160) to start publishing a newspaper.

“But the Soviet ambassador attacked us. He told us we were ultra-’leftists’ and that only Sihanouk could lead the revolution. He told us to never come back.”

For the Kampucheans, this experience only confirmed the need for self-reliance and especially exposed the fact that the USSR was a counter-revolutionary force that could not be counted on for support.

“We expected to hold the founding congress in 1959,” Sary continued. “The repression was so severe, however, that this proved impossible. We left our houses every day in the morning not knowing if we would return home alive in the evening.

“Finally, in 1960, we were able to gather all the representatives together to found the Party. We met for three days from Sept. 28-30 in an abandoned railway building here in Phnom Penh. Our security had to be very tight; no one, could come in or go out during the meeting.”

The congress succeeded in founding the Party, adopting a constitution and electing a Central Committee.

“We had adopted the correct stand on the absolute necessity of the armed struggle,” Ieng Sary said. “But we still had much ideological work to do on this question. We had to educate the party members that the reform struggles–for land, democratic rights, better living standards, etc.–were very important but that they could not give us power. Only the armed struggle, led by the Party, could put political power in our hands.”

By 1963, the CPK leaders realized that they could no longer stay in Phnom Penh owing to the political repression and the growing power of Lon Nol’s right-wing section of the ruling class.

“We left Phnom Penh and went to the northeast countryside in the province of Ratanakiri.”

(To be continued)