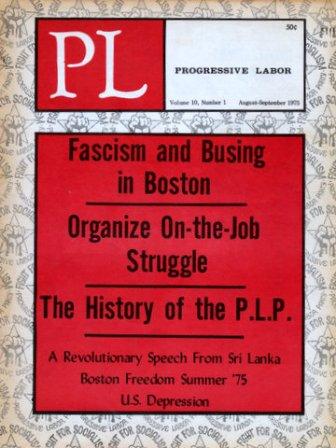

First Published: Progressive Labor, Vol. 10, No. 1, August-September 1975

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The international communist movement has a great history of working class struggle and revolution. Communists have always been in the forefront of workers’ battles for better working conditions, shorter hours and higher wages, industrial unionism, anti-racism and the fight against the exploitation of women. Communists led the fight against fascism and imperialist wars which cost the lives of hundreds of millions of working people in the past century. Above all, communists have been in the vanguard to destroy capitalist society, and have led the workers to establish the first socialist societies in history.

In the course of this great progressive struggle, numerous errors were made which caused serious harm to revolutionary advance. Particularly harmful have been the reversals of the great revolutions in the Soviet Union and China which were analyzed in the PLP document Road to Revolution II.

The PLP does not repudiate the history of the communist movement. We are part of it. We study it and defend it in order to develop it further. Naturally, we cast aside all that is negative while we cultivate all that is positive. We make no absurd claims as to being the first true communist party in history. We struggle daily to rid ourselves of the influences of capitalist ideas. By our adherence to revolutionary communist principles and especially by our actions, which always speak louder man words, we continue to evolve as the revolutionary vanguard of the U.S. working class.

Thus, in a fundamental sense, the history of PLP begins with the earliest strivings of the world’s workers to get rid of capitalist exploitation. PLP identifies itself with the outstanding revolutionary contributions of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and others (despite our sharp criticisms of their mistakes).

Just as socialism arises out of capitalism, the PLP arose out of the old Communist Party which lost its revolutionary outlook and became a prop of capitalism. This process of degeneration of the old communist movement reached its climax at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1956. At this Congress the revisionist (counter-revolutionary) idea of being “pals with bosses” was codified. Peaceful coexistence, peaceful competition, peaceful transition became the cornerstone of international “communist” policy. The Congress repudiated completely the leadership of J. Stalin, and with it the thirty-year history of the first workers’ state’s effort to build a socialist society. Fundamental Marxist-Leninist principles, such as the dictatorship of the proletariat, proletarian internationalism and a democratic-centralist workers’ party were cast aside.

A shock wave swept the entire international communist movement. In the United States, the CP. was thrown into a grave internal crisis. The leadership, which had long been steeped in opportunistic policies, such as support for liberal bosses like Franklin D. Roosevelt, completely panicked. A right-wing group, under the leadership of John Gates, the editor of the Daily Worker, openly broke with Marxism-Leninism. They attacked the concept of a disciplined revolutionary communist party and called for a “mass socialist party” of electoral reform. Their platform was the idiotic demand of “Revolution by Constitutional Amendment,” as if the bosses would simply roll over and play dead because the majority of working people want socialism. (Incidentally, this is still the programmatic outlook of the revisionist “C”P).

The center forces were under the leadership of Eugene Dennis, the general secretary, and William Z. Foster, the chairman. The centrists fought the right-wing Gates forces, who were deserting the party in droves and declaring that they had “wasted the best years” of their lives. As if fighting the bosses’ system of racism, exploitation, war and fascism is a waste! While defeating the Gates’ right-wingers, the Foster-Dennis forces never defeated the revisionists’ class collaborationist program. They failed because they never analyzed the roots of their own revisionist policies; they never repudiated the 20th Congress of the CPSU; they never adopted a self-critical attitude to the history of the CPSU or to the history of the international communist movement.

The Left forces in this critical period had no big-name national leaders. Most were secondary leaders and trade union comrades from the industrial sections of the party. While the Left vigorously fought the Gates right-wingers and were critical of the Foster-Dennis center group, they, too, were divided and confused about the correct course. One group, about 500 strong, broke from the old CP and immediately set out to build a new communist party. Known as the Provisional Organizing Committee for a new communist party (POC), they rapidly disintegrated because: 1) They had no program other than that the old communist party was no good; 2) They continuously split over different personality clashes in their leadership; 3) They mistakenly elevated secondary differences about practical activities to matters of principle and stewed in their own juice.

Other left forces fought for change inside the old CP. Within the year following the 20th Congress, the CPUSA was decimated from top to bottom. In Buffalo, N.Y., for example, the Upstate Organizer quit; the county organizer took off for California without a word to anyone; most community and student section leaders quit. The only sections of the Erie County CP that held firm and fought for a disciplined communist party and revolutionary communist principles were two industrial sections (the public and non-public). Interestingly, these comrades were attacked as “Stalinists” by the revisionists who had deserted the fight for communist revolution.

The experience of the mass desertion of the fight for a revolutionary communist party by the petty bourgeois sectors of the old party was an important lesson to the future leadership of the Progressive Labor Party, several of whom were leading cadres in the two Buffalo industrial sections of the old CP.

As a result of the desertion of the old CP by the right-wing Gates forces and the ultra-left POC’ers, a large vacuum was created in leadership, particularly in NY where 50% of the national membership functioned. A new, younger leadership began to emerge. In Buffalo, Milt Rosen, an industrial worker and leader of the industrial section, became the Upstate NY organizer.

That year (1957) the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) swooped into Buffalo with the aim of finishing off the left-wing’s industrial base. What the revisionists couldn’t do from within, HUAC hoped to accomplish from without with anti-communist hysteria. The reactionary leadership of the United Steel workers, United Auto Workers, and International Electrical Workers cooperated fully with the Un-American Committee. It was these sellout union misleaders that initiated the firing of many communist industrial workers.

Many comrades lost their jobs, particularly those who had followed the policy of hiding their communist views from the workers. HUAC, the FBI and the bosses knew who were party members but the workers on the job didn’t! However, those comrades who were known to their fellow workers as communist fighters were defended from the HUAC attack. In most cases these comrades did not lose their jobs.

This experience pointed up the profound lesson that communists must rely on and trust their fellow workers.

The HUAC attack failed to crush the Left forces in Buffalo. The party organization remained intact and the comrades proceeded to rebuild the Upstate NY organization. In 1959, M. Rosen was elected to be the NY State CP’s industrial organizer.

With the election of new trade union cadres to party leadership in the NY State organization, the struggle inside the old CP sharpened. The left boldly advanced the struggle to openly bring the banner of socialism into the working-class movement. For the first time in many years, open communist street rallies were organized in the NYC garment district.

The national leadership, under the direction of Gus Hall, viewed with alarm the new Left leadership in the NY State party organization. Hall’s political line was to bury the party in the mass movement. Hall maintained that the task of communists was to get party members to become militant reformist leaders. Thus, trade union comrades were to be the best trade union reformers, communists in the peace movement the best pacifists, those in the civil rights movement the best civil libertarians. In elections, we were supposed to support the bosses’ lesser-evil candidate, John Kennedy.

This reformist course was vigorously fought by the Left working-class party cadres. Naturally the Left believed that communists must fight within the mass movement (the trade unions and other mass organizations) for reforms that were in the workers’ class interests, but we insisted that we must do so as communists, and with the aim of winning militant fighters to a communist revolutionary outlook. We also vigorously opposed the entire lesser-evil theory.

Fearful of inner-party ideological struggle, the old party national leadership proceeded to attack the new Left cadres as “anti-party,” even though we functioned strictly within the guidelines of democratic centralism. At the 17th party national convention, the Gus Hall leadership maneuvered to put into national leadership from New York such well known revisionists as Betty Gannett, Clarence Hathaway, Sy Gerson, and others who had been repudiated by the NY convention delegates.

Dizzy with their right-wing triumph at the 17th convention, the Hall leadership then proceeded to mop up the NY “political delinquents” as we were characterized. Behind their haste to eliminate the Left working-class cadres in the old CP was the new crisis developing inside the old communist movement ” the Chinese-Soviet split. While the Left forces had hints of this struggle with the publication of such documents by the Chinese as “Long Live Leninism” and “On the Historical Experiences of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat,” we had no real knowledge of the depth of the struggle or scope of the issues involved.

We were limited because we were very weak ideologically. Having been badly trained politically in the CP, we were very weak on all basic ideological questions ” the state, armed struggle, the dictatorship of the proletariat, etc. However, the opportunism and the degeneracy of the political line and practice of the CP was made much clearer by the polemics which finally developed openly between the Albanian CP, the Chinese CP and the CPSU.

The struggle of the Left forces inside the old CP was a fight over the revisionist line and practices of the CPUSA. Unlike the numerous pro-Mao groups that emerged after the Sino-Soviet split, the founders of the Progressive Labor Party split from the old CP before open polemics began between the Chinese and Soviet parties.

This independence was a reflection of both a strength and a weakness. The strong aspect indicated that these new PL cadres would stand on our own feet and pursue a course that was in the revolutionary interests of the international working class based on our own collective understanding of Marxist-Leninist principles. We would not be a mere echo or baton-follower of any guru. The weakness stemmed from our low ideological development, particularly, the influence of nationalism. We failed to see at that time that the historic roots of the CPUSA’s revisionism was really international in scope. We did not fully understand that U.S. revisionism is no more an exceptional phenomenon than is the U.S. road to revolution.

After a protracted struggle over line inside the CP, the Gus Hall leadership, fully aware of the developing Sino-Soviet struggle and fearful of large-scale defections, moved to expel the new Left cadres. Hall and Co. knew that we would be sympathetic to the revolutionary international forces and support the Chinese side in the fight. So, in the winter of 1961, the industrial cadres who had taken the lead inside the old party to defeat the revisionists were expelled.

In December of that year twelve comrades representing about thirty-five communist workers, and fifteen communist youth who were known as the Call Group (a communist student-based group strongly influenced by the Cuban revolution, who called for a new communist party), met to shape the future.

At the December, 1961 meeting Milt Rosen gave a political report projecting the perspective to build a new communist party in the United States. We realized the enormity of this task. Many other groups who had come into collision with the revisionist CP had proclaimed a similar goal. All had gone down the drain. We were convinced that others had failed because their entire focus was wrong. These other groups degenerated into small “left” sects because they concentrated their efforts on fighting the old communist party. But who was interested in such matters? Only a small number of ex-CP’ers, not the mass of the U.S. working class.

We resolved not to fall into that sectarian trap, but rather to concentrate our efforts on developing a revolutionary program with a mass line and with the aim of building a new working-class base. Toward that end we decided to publish a journal called Progressive Labor.

At the meeting there were several disagreements. One of the most important was a debate over the question of whether or not we should refer to ourselves as Communists and Marxist-Leninists. All at the meeting regarded themselves as such, but should we be open about it? This question arose because of the influence of the Castro Revolution which was proclaimed as a socialist revolution. Castro’s movement was known as the July 26th movement, a revolutionary democratic anti-fascist movement. Only after coming to power did he proclaim himself a Marxist-Leninist and communist. The Cuban revolution had great appeal to young comrades.

“Let our enemies call us communists. We won’t deny it or admit it, but we will just go about our business of building a socialist revolution.” This is how some of the young student comrades argued. This view was vigorously opposed. The trade union comrades cited their experiences that anti-communist ideas among the workers cannot be defeated by hiding our communist principles and aims. Indeed, it was pointed out that Marx and Engels had long ago declared in the Communist Manifesto that “Communists disdain to conceal their views.” After a sharp comradely debate, agreement was reached on this important principle, without which it would be impossible to defeat revisionism and other anti-communist ideas or to build a mass communist party.

Another issue that divided some of the founding members of PL was where to concentrate our efforts. Some of the student comrades believed that they should go South. It was felt that in the South the contradictions of U.S. capitalism were sharpest, the workers mainly unorganized and more exploited than in the North, and where the anti-racist struggle was rapidly developing. While these arguments had merit, the trade union comrades believed we had very limited forces and resources, that we should not spread ourselves too thin to begin a new movement, and instead advocated that we should concentrate in N.Y. where we had a small base. However, because the younger comrades were very anxious to pursue this “Southern strategy,” it was agreed that we should support the efforts of a few comrades to work in the South.

The December meeting was a great success. It proved we could openly debate differences and arrive at conclusions that would be based on firm adherence to matters of principle, and flexibility on matters of practical policy. As a result, a new unity between trade union and student communist cadres was developed and the Progressive Labor Movement was born.

In July, 1962, fifty delegates from eleven cities met at a conference called by the editors of PL magazine which had been published monthly since January of that year. This meeting at the Hotel Diplomat in New York City became the founding conference of a new national Marxist-Leninist organization called the Progressive Labor Movement.

The meeting was marked by an intensive debate over the main political report presented by Milt Rosen. The report set forth the objective for a national organization to build the foundations for establishing a new revolutionary communist party. Before a new party could be launched four key tasks had to be achieved: 1) We must develop a revolutionary Marxist-Leninist program. 2) We must boldly initiate militant mass struggles around the immediate needs of U.S. workers and students, and build single issue mass organization, such as unemployment councils. 3) We must develop a base of support among young workers and students and win them to Marxist-Leninist ideas. 4) We must establish a network of clubs and collective leadership. The organization would be loose in form and we would use the principles of flexibility and persuasion to develop united action on policies. “Organize, organize, organize!” concluded the report.

The report was hotly disputed from the “left” and the “right.” The “left” urged that the new organization should be the party, itself. While agreeing with the tasks that the report set forth, the “left” argued that these were continuing tasks of not just an organization to build foundations for a party, but to build the party itself.

In reply to this objection, the majority of the comrades said that because we were a new group, without a clear M-L program and relatively unknown to the mass of the workers and students as well as to one another, we should not try to function at this early stage on the basis of democratic centralism. Democratic-centralism is the organizational principle for a communist party ” a serious communist party requires a high level of discipline and an authoritative national leadership. At this early stage, a much looser form of organization would open the doors to revolutionary young workers and students who would help us build the foundations for a new party. However, it was agreed that our objective must be to establish a disciplined party that would function according to the principle of democratic centralism which required that the minority carry out the decisions of the majority.

The main opposition to the Conference report came from the “right.” The “rightists” proposed an entirely different direction for the new organization. They argued that the working class didn’t need a communist party ” a vanguard M-L type of organization to lead the class struggle. “The workers struggle daily without us,” they declared. “What is needed is a communist educational organization ” an organization to bring communist ideas to the workers.”

This anti-party, anti-leadership view was overwhelmingly rejected by a vote of 48 to 2. Trade union (T.U.) comrades cited their experiences in strike struggles and on-the-job actions. We spoke of the history of organizing the labor movement and the leading role of communists. Workers fully understand the need for leadership and discipline to beat the bosses. Only those who stood apart from the working class could view their role as “educational pundits” and not as fighting communist leaders.

“Of course workers struggle daily with or without communists,” the T.U. comrades said, “but they struggle more effectively with communist leadership. But more important, it is only through active participation by communists in day-to-day battles that workers can really grasp the ideas of communism and of the necessity for a communist party to lead the workers’ revolution for socialism.”

The conference adopted the report with only two dissenting votes. A national coordinating committee was elected to guide the work of the new organization. We agreed to call ourselves Progressive Labor Movement because PL magazine had played the key role in setting forth the generally agreed upon policies that represented a communist alternative to the old revisionist “C”P. The word “Movement” was adopted instead of “organization” to stress the fact that we were a transitional organization that would be moving in the direction of founding a disciplined party.

The PLM founding conference gave great impetus to the growth of a new revolutionary U.S. communist movement. We opened up community PL centers on the Lower East Side of New York, in Harlem, and wherever we had enough forces in other cities, such as Williamsport, Pa., and Buffalo, N.Y. We hit the streets with public rallies. For the first time in many years the banner of Socialist Revolution was brought openly to the workers and students. We participated in developing various community struggles against slum landlords, police brutality and unemployment. We directed our main fire at the liberal bosses and the Kennedy Administration which were “critically” supported by the old CP. revisionists. Four national campaigns in these early years (1962-1964) in which PLM played a leading role indicate how our small organization began to emerge in the forefront of the revolutionary movement in the U.S. These four nationally significant struggles were: The Hazard Miners Solidarity Campaign, The Student Trip to Cuba, The May 2nd Movement, and the Harlem Rebellion.

In the winter of 1962-63, the coal miners in the Appalachian Mountain Region of Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia were engaged in a bitter all-out strike struggle. The strike was a rank and file rebellion against inhuman working conditions and starvation wages. (The average wage was $25 a week!) The struggle for union standards had reached the level of armed struggle in defense of the strike. The mine owners, the police, and local government officials had initiated a campaign of terror and scabbing to break the strike. The strike was several months old when PLM first learned about it. We had a small force in the South (recall the agreement of the December meeting? ) But we had no base at all among the miners.

One of PL’s southern comrades went to Hazard, Kentucky which was the strike center. He interviewed Berman Gibson, rank and file leader of the strike. A telegram was dispatched to PLM headquarters in N.Y. urging an all-out relief and solidarity campaign. Immediately, the National Steering Committee of PLM met and decided to make the Hazard Miners struggle the main focus of our work. A bold national campaign of support was launched. The strike was given national publicity. A national TU Solidarity Committee was organized under the leadership of Wally Linder. a PL member and the president of his local union RR lodge. Food, clothing, and funds were, collected in working class communities across the country wherever we had PL readers and PLM members. The issue was raised in local unions to send truckloads of food.

A key feature of the strike was the participation of black miners. Although black workers made up a relatively small percentage of the population in the Southern mountain region (as compared to the delta areas), they played a big role in the strike. The example of black and white workers united side by side and armed had sent the local bosses and politicians into a frantic rage. Significantly, the bosses’ news media, N.Y. Times, CBS, NBC, A.P., etc., never mentioned the fact about the unity of black and white miners in all the publicity they gave to this strike.

We also raised funds for a mimeograph machine for the miners to put out their own local paper to combat the lies of the Hazard Herald and other bosses’ news media. A mass meeting was organized in New York with Berman Gibson as the featured speaker. More than a thousand workers attended:

The bosses and their stooges went wild! “Communism comes to Kentucky!” headlined the local Kentucky newspapers. The “C”P revisionists were aghast at how the insignificant PLM could initiate such a bold national solidarity campaign. The Trotskyites and such sectarian groups of ex-C.P.’ers as “Hammer and Steel” sniped at PLM for doing “missionary” work, as if strike solidarity was not a critical question of class interest for all workers.

The response of the miners and most rank and file leaders was terrific. The response in numerous workingclass communities and among rank and file trade unionists was also terrific. From the outset it made clear to the miners, to Gibson and other leaders that PLM was a revolutionary communist organization. We made certain that they knew about our communist aims because some of us had had enough experiences inside the old CP. with the bad effects of the opportunist policy of concealing communist ideas.

We anticipated that the bosses would resort to redbaiting, as indeed they did. At first Gibson and other rank and file leaders resisted the anti-communist crap, but as intensive redbaiting mounted, Gibson and others retreated and disassociated themselves from PLM.

The Kennedy liberals and social democrats noted that a very dangerous situation was developing for the bosses ” that is, a situation where armed workers, black and white, were uniting with communists to fight back! They decided to step into the picture. With big $$ and lots of resources, the liberals set up their own solidarity committee. Gibson and others broke with PLM, and turned to the liberals.

The strike continued for many months but ultimately petered out.

Vital lessons were learned in the course of this great strike and solidarity campaign. Among the more important ones are these:

� Workers will fight with guns-in-hand to defend their fundamental class interests when they deem it necessary.

� Strike solidarity is a crucial issue to all workers and they will respond enthusiastically when bold leadership is given.

� The bosses never hesitate to use violence to break a strike, but their ace in the hole is anti-communism, especially when racism has failed to break the fighting unity that has been forged between black and white.

� The left can not defeat redbaiting without a mass base. Furthermore, a solid communist working class base cannot be established outside the ranks of the workers. Such a base can not be achieved quickly in one or two battles. Only through protracted class struggles with communists giving active leadership from within the ranks of the workers, will workers shed their anti-communist prejudices and see that communist ideas are in the best interests of our class.

The Cuban Revolution had great appeal to young people in the U.S. and especially to black and Latin workers. The U.S. ruling class was fearful that the Cuban revolutionary experience would spark revolution throughout Latin America and also radicalize U.S. workers and students. The Kennedy administration had failed miserably to crush Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. In October, 1962, the Kennedy boys (John and Robert) played brinkmanship with Nikita Khrushchev in the famous eyeball-to-eyeball missile crisis which was said to have brought the world to the threshold of nuclear war.

Never having any illusions about the Kennedy administration, PL had anticipated Kennedy’s invasion plans. We issued tens of thousands of leaflets, held street rallies and unfurled the first Hands Off Cuba! banner in the galleries of the United Nations.

To isolate Cuba, Kennedy had declared an economic boycott and travel ban on Cuba. Groups, like the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, under Trotskyite influence, had emerged to issue pro-Cuba propaganda and reprint Castro’s speeches, but they didn’t dare do anything to develop a mass struggle. At the same time that we had developed the Hazard Miners Solidarity Campaign, the young PLM boldly announced that we would break the travel ban on Cuba and openly confront the State Dept.

More than five hundred students had contacted PLM to join with us in defying the State Dept. travel ban. Out of the 500 applicants, 75 U.S. students were selected to go by the PL-led Ad Hoc Committee to Travel to Cuba. An official invitation was secured from the Cuban Federation of University Students. Intending to spend their Christmas vacation in Cuba, the U.S. students entered Canada to fly on a Cuban plane. Acting in collusion with the U.S. State Dept., the Canadian government refused to give the plane a landing permit and the trip was temporarily blocked.

The revisionists and Trotskyites laughed at us. They called us “crazy adventurists” and declared that we would never get to Cuba. However, we anticipated these difficulties and had an alternative plan which combined public and nonpublic methods.

After failing to go via Canada, we publicly announced that the next effort would be to go via Mexico. We even told the students who were planning to go that Mexico would be the route. We knew that the FBI, CIA and State Dept. would try to infiltrate our ranks with agents. Actually, only a few comrades knew about arrangements to go via Czechoslavakia. The real plan was to fly thousands of miles to Europe and back in order to go to Cuba, which is only 90 miles off the Florida coast.

The plan came off smoothly, in the summer of 1963. Fifty students crashed the Kennedy curtain and traveled to Cuba. The ruling class was furious and the CP. revisionists and Trots were dejected.

When the students returned to the U.S. and landed at Idlewild (now called Kennedy) Airport, the U.S. immigration officials began to mark their passports “invalid.” The students refused to turn their passports over to them. The immigration officials retreated and the students kept their passports. Within a few weeks, PLM leaders and Ad Hoc Committee members were hauled before a Grand Jury hearing considering conspiracy charges. We were said to have conspired to break the travel ban. What a conspiracy – we had publicly announced that intention for almost a year!

More than fifty members and friends of PLM were either cited for contempt or indicted. Some comrades and friends faced up to 20 years in jail! This effort to terrorize and punish the young PL’ers and their friends for daring to defy the U.S. government failed miserably. Of course, a few defected. One of the more notorious ones was Phil Luce, a Travel Committee leader and PL’er who also faced 20 years in jail. In desperate fear he turned to drugs, became an FBI informer, wrote an anti-PL book under the auspices of the Un-American Activities Committee, and was last heard of as being a leader in the ultra-reactionary YAF (Young Americans For Freedom).

Most of the young PL comrades and friends held firm in the face of the attacks and grew stronger and more committed to fight the U.S. ruling class. A national campaign to defend the Student Travelers was launched and received widespread support.

The best answer to the indictments and harassment was given when we dared to organize another trip. This time about 84 students went – almost a thousand wanted to go. The ruling class decided that they better cool it. After a fight that went all the way up to the Supreme Court all the charges were dropped. A full victory was obtained. The travel ban was broken; the State Dept. was confronted and beaten! Many students joined the new PLM in the course of this struggle and PLM began to emerge as a new vigorous force in the emerging new left in the U.S.

Every struggle contains lessons, new and old, and the Student Trip to Cuba Campaign proved to be very educational:

� It is necessary to anticipate the attacks of the ruling class and to develop alternative plans to defeat those attacks.

� We must learn to travel many different avenues of struggle to smash the bosses.

� Be bold – dare to struggle and dare to win! We must dare to fight the bosses. We must dare to speak out loud and clear on matters that others only whisper about. We must dare to undertake campaigns that others only dream about. We must always be guided by the principle of acting in the best interests of the international working class.

� We grow stronger only through struggles. Ruling class terror will never destroy the communist movement but our own fears and timidity can turn formerly good fighters into corrupt renegades.

In March 1964, a conference on socialism was held at Yale University. Numerous self-proclaimed socialist and communist organizations were invited including the “C”P revisionists and various Trotskyite groups. PLM was also invited and we decided to participate.

The conference was supposed to be only on a theoretical plane and to debate ideological differences without getting into any practical political proposals. This ridiculous anti-Marxist-Leninist approach to socialism was adhered to by all the so-called revolutionary groups except PLM. We refused to go along with such bourgeois academic ground rules that make a mockery of communist ideology by trying to separate it from practical working class action.

Breaking through the academic nonsense, PLM spokesman Milt Rosen electrified the audience of more than 500 students and faculty members by discussing real life. He particularly focused on the Vietnamese revolution and the efforts of U.S. imperialism and international revisionism to crush it. Furthermore the PLM chairman proposed that the conference should support a nationwide mobilization on May 2nd to protest U.S. aggression in Vietnam.

The proposal was overwhelmingly approved by the conference and a May 2nd Committee was organized under PLM leadership. On May 2nd thousands of students and workers marched and rallied in numerous cities across the country demanding that “U.S. GET OUT OF VIETNAM NOW!” The May 2nd action was the first national demonstration against U.S. aggression in Vietnam! It was the forerunner to the millions of protesters who were to march against U.S. imperialism in the years ahead.

To maintain the momentum of the May 2nd demonstrations and to organize a national anti-imperialist peace movement the May 2nd Committee decided to become a national membership organization and called itself the May 2nd Movement (M2M).

Hundreds of young people joined M2M. Many of the students who had participated in the Travel To Cuba struggle became leaders of the organization.

The youthful and militant May 2nd Movement played a major role in popularizing the struggle against U.S. imperialism in Vietnam. It issued hundreds of thousands of leaflets, buttons, pamphlets etc. It initiated numerous Vietnam Teach-ins in universities across the country. It organized rallies and marches. In addition to its anti-imperialist activities, the M2M also developed the Free University movement as an off-campus alternative to the bourgeois educational system.

Many students were attracted to M2M and its offshoot activities. However the organization was infected with several fatal weaknesses that prevented it from emerging into a powerful anti-imperialist mass movement. These weaknesses were: 1) Drugs, 2) Sectarianism and 3) Racism.

It is no accident that the drug culture rapidly developed in the early 1960’s. Drugs have always been around, but they were especially pushed by the U.S. ruling class in the 60’s to divert young people from struggling against them. The Boss controlled media told young people to “tune in, turn on, and drop out.” They tried to make the drug culture appear to be “anti-establishment” but it was just the opposite. They were really telling young rebel fighters to “tune in to bourgeois culture” and “to turn on to drugs” in order “to drop out of the antiwar and civil rights movements.”

Is it any wonder that Berkeley, the scene of the first major student strike of the 60’s – the Free Speech Movement – became a national center of the Drug Scene?

PLM vigorously opposed the use of drugs which had widespread influence inside M2M and had even penetrated to some young comrades in PLM.

While PLM succeeded in purging its own ranks of drug users we never won the struggle inside M2M. Unfortunately, many fine young fighters degenerated politically by becoming drug users.

As the Johnson Administration stepped up U.S. aggression in Vietnam, new forces emerged to enlist in the growing mass anti-war movement. Along with the growth of M2M, many other anti-war organizations also began to flourish, such as Vietnam Day Committees and especially the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

Instead of striving to unite with these forces, many M2M’ers as well as some PL’ers viewed these other anti-imperialist war fighters with disdain and even contempt because “they are not as radical as we are,” or because “they’re under the influence of a bunch of phony liberals and revisionists.”

A sharp struggle developed inside PL as it did inside M2M over the question of uniting with and merging with SDS. SDS had grown into the major center of radical student politics following its massive Washington anti-war rally in the Spring of 1965. The PL leadership vigorously fought both inside its own ranks and inside M2M against a sectarian line of isolating ourselves from the new anti-war forces that were developing on a vast scale throughout the U.S.

After an intensive struggle both inside PL and M2M the overwhelming majority supported the line of dissolving M2M and joining SDS. A small group of PL’ers quit over this difference in tactics and attacked the leadership as “opportunistic” and “revisionist” for dissolving M2M. They tried to maintain M2M and the Free University as a viable alternative to the actual mass movement but they rapidly evaporated.

Perhaps the most serious weakness in M2M was its failure to develop the struggle against racism and to link the anti-racist struggle with the antiwar movement.

This weakness was directly related to the wrong line PL had on the question of Black Liberation at that time. We failed to understand the class nature of racism and the struggle to destroy it as being a life and death question for white workers as well as black workers. The fight against racism was never a central question in the M2M as it should have been. As a result of racism M2M never succeeded in building any base among black youth nor any unity with the growing militant black student organizations, such as SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee).

To understand M2M’s positive significance we must recall the character of the old anti-cold war peace movement which was strictly pacifist. Completely dominated by the old “C”P revisionists the old peace movement was never anti-imperialist. The “C”P pushed instead a policy of international class collaboration with such slogans as “Ban the Bomb” “Summit Negotiations to Ease International Tensions” “Peaceful Co-existence” “For a Sane Nuclear Policy” etc.

Despite the serious weaknesses we discussed above and which ultimately destroyed the organization, M2M played a vanguard role in the struggle against U.S. imperialist aggression in Vietnam. It also represented a break with the old pacifist peace movement, and it helped move all the new emerging anti-war forces in a more left, anti-imperialist direction, especially the SDS. Many fine young fighters joined PL as a result of their experiences within the mass struggles of the M2M. We also learned more about Marxist-Leninist principles and tactics, such as:

The left must never isolate itself from the mass movement. We cannot be mere agitators or propagandists. We must be an integral part of the mass struggle, strive to give leadership from within and raise our communist ideas as we fight side-by-side with those who disagree with us. No mass organization can sustain a progressive course without elevating the struggle against racism to a top priority.

On February 1, 1960, the civil rights struggle took a qualitative turn when a group of black students in Greensboro, North Carolina began a sit down at a lunch counter of the Woolworth store. Within two weeks the sit-ins spread like wildfire to 15 other cities and within a month to 33 more.

This bold confrontation with the racist Jim-Crow system was not initiated by any big shot leader, not by the revisionist “C”P but by a black student, McNeil Joseph, who was fed-up with racist discrimination and decided to do something about it.

As far as the revisionists were concerned, Ben Davis, a national “Communist Party” (CP.) leader, told the 17th Convention of the “C.”P. that “if the Greensboro students would have come to us for advice about the sit-in we would have told them not to do it and would have called it adventuristic.”

The sit-ins of 1960 were followed by the Freedom Rides of ’61 and then wade-ins at beaches, swim-ins at pools, kneel-ins at churches and lie-ins at construction sites. By August of 1963 the civil rights movement reached its zenith with a massive march on Washington of more than 200,000 to hear Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech.

The tempo of the rapidly growing movement could be measured by the fact that in the ten week period following massive demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama in the Spring of 1963, there were (by official U.S. Department of Justice reports) 758 different mass demonstrations and 13,786 arrests. (They didn’t give figures on the killings, the beatings, the bombings, the police dog bites, the fire hosings and other brutalities against the people.)

The struggle against racist oppression took two main forms: In addition to the integration movement, the nationalist movement also grew in scope and militancy in the early 60’s. In Monroe, North Carolina, Robert Williams broke with the NAACP and set forth a nationalist line for armed struggle. He attacked the NAACP and King for their nonviolent middle class program. While attracting some national attention, the Williams’ group evaporated when Williams fled to Cuba in August 1961 to escape trial on “kidnapping” charges.

The most important nationalist force to emerge in the early 60’s was the Muslims. This religious organization was founded around 1932 by Elijah Muhammad, but its most famous spokesman in the early 60’s was Malcolm X. Malcolm X vigorously and persuasively spoke out against the integration movement, its collusion with racist liberal politicians, and its submission to racist violence. When attacked by the cops, the Muslims fought back. They developed their own armed self-defense unit. They recruited large numbers of rebellious black youth from the jails and from the streets.

The Muslims grew by leaps and bounds. Their membership figures were secret but based on turnouts at rallies and conventions estimates range up to 12,000 members and 50,000 supporters.

The surging integrationist and nationalist movements both reflected the anti-racist mood of the black masses. On the surface, the leadership of both these movements seemed to be pushing in two opposite directions: the civil rights movement for integration with whites and the nationalist movement for a separate state for blacks. Both these movements, however, were united in their devotion to capitalism. The integrationists were headed by leaders who wanted to integrate into the white capitalist superstructure on a parity with the white bosses. The nationalist leaders said that this was a pipe dream and that we must aspire to have our own capitalist factories, stores and farms in order to make a big profit. The perspective held out for the black working masses was not an end to exploitation but the opportunity to be exploited by black bosses instead of white bosses.

While PL’s line on Black Liberation was not correct at that time, we always set forth the correct strategic position that only a socialist revolution could end the racist capitalist system. This revolutionary perspective differentiated the young PLM from the revisionist “C”P and SWP. The revisionist “C”P and the Trotskyite SWP had long tailed after one tendency or another within the black liberation struggle. In this period, the “C”P gave all-out support to King and the SWP backed Malcolm X. Neither group adopted a critical class analysis of the two black capitalist oriented movements.

In our early years, PLM was strongly influenced by the view, most clearly articulated by Mao, that nationalism had two aspects: One aspect was reactionary because it attacked the workers of the foreign imperialist nation; the other aspect was revolutionary because it attacked the bosses of the imperialist power. This position led us to align ourselves more with the nationalists than with the integrationists. However, we always maintained a critical line toward both, while we directed our main fire at the liberal Kennedy and Johnson Administrations who backed King.

It was within this setting of a rising national anti-racist movement and our weak ideological class analysis that the leading role of the young PLM in the historic Harlem Rebellion of 1964 becomes so significant.

Prior to the Harlem Events of 1964 PL had some experience in the South and in the ghettos of New York and Buffalo. In the South we worked with SNCC and also with the Williams forces in Monroe. Our main concentration was in Harlem.

In early 1963 we opened a PL center in Harlem, headed by Bill Epton who had been a rank and file activist in the Negro American Labor Council. Our work focused on the development of a mass movement against police brutality and the organization of self-defense councils. Police terror had become a central issue throughout the country. The ruling class had tried to stem the growing tide and militancy of the “Freedom Now” movement by granting numerous reforms, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which outlawed discrimination in all public facilities. But while they held out these “carrots” to placate the masses, the bosses heightened their use of the “stick” in the form of horrendous acts of racist police brutality.

Week after week, PL held street rallies in Harlem exposing case after case of police brutality. We also organized numerous demonstrations in front of local precinct headquarters. On June 11th, 1964, the murder frame-up case of the Harlem Six, the cop clubbing of John Morton while he was handcuffed, the police assault on Eladio Rivera.

When Lt. Gilligan murdered in cold blood 15 year old James Powell the raging anger of the black masses reached the boiling point and Harlem broke out into open rebellion. Thousands of militant youth took to the streets. The focus of their anger was on the cops and the local price gouging stores that the cops protected. Molotov cocktails were hurled at police cars and numerous stores were burned. Thousands of cops were rushed into the area to quell the revolt, but the rebellion spread. Thousands of shots were exchanged.

Mayor Wagner and Police Commissioner Murphy issued a proclamation putting the city under virtual martial law by outlawing rallies, demonstrations and marches. All the civil rights leaders were called in to try to smash the rebellion by telling the people to “cool it.” Wagner brought in King, Roy Wilkins, James Farmer, Bayard Rustin and other big shot “leaders,” but the rebellious masses ignored them and Life magazine lamented that “Decent Negro leadership has collapsed.”

“The fact is that the only force that had the guts to give political direction to the spontaneous rebellion was PL.”

The masses were in motion and indeed they were seeking leadership ” revolutionary leadership. “Where’s Malcolm?” many asked. Malcolm X had broken with the Muslims in March of that year and was on a tour of Africa. Wagner had rushed back on behalf of the ruling class from his vacation in Spain with his fascist chum Franco, but Malcolm didn’t see fit to return from Africa to give leadership to the rebellion. He was too busy making it with Allah and big shot African governmental officials.

As for the revisionist “C”P and the Trotskyites, no one had to tell them to “cool it” because they were already in a deep freeze as far as Harlem was concerned.

The fact is that the only force that had the guts to give political direction to the spontaneous rebellion was PL. Thousands of posters demanding “WANTED FOR MURDER, GILLIGAN THE COP” with Gilligan’s picture were circulated throughout Harlem. Hundreds of young rebels came to the Harlem PL center for leaflets and posters. In defiance of the Wagner ban on rallies and marches, PL organized a massive rally and march.

We also pointed out that the rebellion was directed not only at police terror but at the racist conditions of life in Harlem. Racist law and order in Harlem meant that the Harlem median family income was $3,995 compared to NYC $6,100, that unemployment in Harlem was 300% higher than in the rest of the city, that sub-standard housing was 49% while in the rest of NYC it was 15%, that infant mortality was 45.3 per 1000 births but only 26.3 in the rest of the city.

PL was violently attacked by the bosses’ media for “inciting riots.” The renegade and cowardly “C”P attacked us as “adventurists.” The lives of PL leaders were threatened. The NYC red squad tailed and harassed PL leaders 24 hours a day.

Epton and other PL leaders were arrested and indicted for inciting a riot and for violating an ancient anarchist conspiracy law. The faced up to 20 years in jail! The PL printers who made the Gilligan posters were also arrested and jailed! Numerous members of PL were subpoenaed before a grand jury and faced contempt citations. Freedom of speech, press and assembly is cast aside when the bosses deem it necessary.

A nation-wide defense campaign was launched. While the Harlem rebellion subsided in a few weeks, its impact on the entire country was enormous, and the prestige of PL soared in the black communities. For example, in the Fall of 1964, Bill McAdoo came from Harlem to be the main speaker at a mass defense rally in San Francisco. PL was virtually unknown in the S.F. Bay area black communities. But because of our leading role in the Harlem Rebellion, almost 500 black militants came to hear the PL spokesman’s on-the-scene report of the struggle in Harlem.

Unfortunately, we were not able to maintain this leading position because of our incorrect line and poor organizational leadership at that time.

Our weaknesses in organizational leadership, for example, were reflected in the fact that we ignored such fundamentals as getting the names, addresses and phone numbers of hundreds of young people who had come to the Harlem Headquarters during the rebellion and to the rallies, marches and demonstrations. In the enthusiasm of organizing during the rebellion we got swept up in the historic importance of the immediate battle and forgot about organizing for the long war ahead to destroy capitalism.

Above all, our political line was not correct, being influenced by nationalism. In practical terms we had the perspective that white comrades should work among white workers and black comrades should work among black workers. This line disunited the fight against racism. It undermined collective leadership, criticism and self-criticism and collective responsibility for developing the strategy and tactics to lead all aspects of the class struggle.

As a result of these weaknesses we failed to raise the revolutionary class consciousness of the hundreds and thousands of young militants who admired PL for daring to give some leadership to the rebellion. Consequently we did not consolidate this potential base for the new revolutionary communist party PLP, although we did recruit a few of the rebel fighters into our ranks.

This lesson can not be overemphasized:

It is not enough to organize leaflet distributions, mass marches, rallies, and wall posters. It is not enough to seize the moment to give leadership to an immediate battle no matter how sharp. We must do more. We must organize the masses not only to fight now but for the future. Of course this not only requires obtaining names and addresses of bur friends and supporters to visit them, but to organize study-action groups, sell our party literature, and involve the new forces in collective political discussions on the strategy and tactics of the fight so as to help train them as well as ourselves as Marxist-Leninist revolutionary leaders. The Harlem Rebellion and PL’s role again reinforces the point that revolutionaries must rely on the masses and not on alliances with class enemies who sell the people out. By daring to give leadership where others fear to tread we can emerge as a real workers’ revolutionary vanguard.

Just as the sit-in movement in Greensboro, North Carolina initiated a new stage in the civil rights movement, the Harlem Rebellion raised the movement to a new level. A grave credibility gap developed between the repudiated, exposed, reformist leaders and the militant black masses. No longer would King’s advice to the black masses that “if blood is to be shed, let it be our blood” be tolerated. Instead the battle-cry of the people became “Burn, baby, burn!” meaning that we will burn this racist system to the ground.

Thus following Harlem, more than 100 cities throughout the U.S. felt the torch of rebellion and the ruling class shuddered in realization that this was only the spark of the workers’ revolution yet to come.

The fight against counter-revolutionary ideas has always been a central feature of the history of the working class movement. Marx and Engels combated the anarchist views of Proudhon and Bakunin. Lenin opposed the revisionism of Bernstein and Kautsky. Stalin fought Trotsky’s line that socialism could not be built in a single country.

These great debates were not abstract academic speculations over how many fairies can dance on the head of a pin, but vital life and death questions for the workers of the world.

The triumph of Marxism in the 19th century meant that thereafter the working class would strive to end its suffering under capitalism by advancing the strategic aim of socialist revolution. Lenin’s victorious ideas led to the October revolution and the first socialist state. Stalin’s victory gave the workers the opportunity to build history’s first socialist economic system.

The emergence of PLM in the early 1960’s coincided with another great ideological struggle of international significance ” the Sino-Soviet dispute. The founders of PLM had engaged in a protracted internal struggle against the reformist policies of the old “C”P leadership. However, we did not have a good understanding of the depth of the revisionism that had grown like a cancer over the whole of the old communist movement. In this regard, the anti-revisionist contributions of the Communist Party of China were of great importance to the young Progressive Labor Movement of the U.S. as well as to revolutionary communists throughout the world.

You will recall that at the founding conference of the Progressive Labor Movement in July, 1962 (see Part II) four tasks were adopted to build the foundations for a new revolutionary communist party in the U.S. These tasks were:

1) the development of a revolutionary Marxist-Leninist program,

2) the initiation of militant mass struggles around the immediate needs of U.S. workers and students,

3) building a base of support among new forces and winning them to communist ideas,

4) building a network of clubs and collective leadership.

The bold leadership the young PLM organization gave in the Hazard Miners Solidarity Campaign, the Student Trip to Cuba, the May 2nd Movement, the work in the South and in the Harlem Rebellion as well as numerous local struggles attracted a relatively large number of revolutionary-minded students and young workers into our ranks.

To help weld the necessary ideological unity around a revolutionary program, following the founding conference the National Coordinating Committee issued a Prospectus for a new theoretical journal, the Marxist-Leninist Quarterly, to be published by the end of that year.

The Prospectus and MLQ’s lead editorial had a basic contradiction in PLM’s ideological position. For example, the Prospectus noted that... “revisionism is a dangerous and self-defeating folly not only because it leaves little room for independent action and propaganda on behalf of socialism, but more important, because it represents an unwillingness to see that the liberalism of the Kennedys and Rockefellers is a sophisticated, flexible instrument of imperialism that shares with the ultra-right the goal of capitalist world domination. Such revisionism has led to reliance on support of allegedly “advanced” or “progressive” sections of the ruling class instead of reliance on the working class and on the opportunities presented by sharpening class struggles.”

At the same time that we castigated revisionism, we also stated in the MLQ that “We do not want to enter into a fratricidal war with the CPUSA... nor with the SWP, nor with any other socialist group... We seek only a frank exchange of differences and, whenever possible, a coordinated struggle against the imperialist enemy.” Hence, we declared that we were ready to fight revisionism, but unwilling to fight revisionists. Such a contradictory position was untenable and inevitably led to PLM’s first major internal ideological struggle following the fight with the “Educational Associationists” at the PLM founding conference.

Two factors gave impetus to the necessity to resolve the above contradiction. One was the open polemics that swept the old communist movement and the other was the internal growth of PLM and its developing mass base.

New members and friends wanted to know more clearly what were our ideological and political differences with the old “Communist” Party, and also how we viewed the Sino-Soviet debate.

On October 23rd, 1963 Milt Rosen, PLM chairman, gave a comprehensive political-ideological report on the fight against revisionism to the National Coordinating Committee. This report became the basis of a national PLM discussion that lasted more than three months. It was revised several times based on suggested changes by PLM members and published in pamphlet form around March 1964, under the title Road to Revolution.

The document begins with a clear statement of the difference between the revisionist road and the communist road for the working class. It says: “Two paths are open to the workers of any given country. One is the path of resolute class struggle; the other is the path of accommodation, collaboration. The first leads to state power for the workers which will end exploitation. The other means rule by a small ruling class which continues oppression, wide scale poverty, cultural and moral decay and war.”

The scope of the 126 page pamphlet can be gleaned from some of its chapter titles: U.S. Workers Require Revolutionary Theory, Fear of Revolution Sparks an Imperialist Counter-offensive, Fear of Imperialism Sparks Revisionism, The Origins and Results of Class Collaboration in The U.S., Black Liberation: Key to Revolutionary Development, What Kind of Peace Movement is Needed?, Revisionism in the International Movement, A Period of Revolution, The Chinese Communist Party Fights for Marxism-Leninism, Build a Revolutionary Party in the U.S.A.

Road to Revolution was the most important policy declaration since the founding of PLM. It linked the “great debate” between Marxism-Leninism and revisionism in the international communist movement to the development of the revisionist degeneration of the “C”P of the United States and analyzed its significance for the U.S. working class.

The document represented a devastating ideological assault on the old “C”P. It summed up the history of the old communist party and indicated that “From the earliest days of the communist movement in the U.S. to the present, revisionism and its political manifestation, class collaboration, has been the chronic weakness ... (and that), on balance, despite thousands of revolutionary-minded members, the “C”P was a party of reform, not revolution.” The document shook up a number of former “C”P members who had joined PLM.

The main opposition came from the S.F. Bay Area PLM Executive which voted four to one against publishing Road to Revolution and against any open polemics with the old “C”P.

The arguments they raised were along the following lines:

� The struggle against revisionism would not be aided by polemics against the “C”P because the old “C”P is without influence.

� We defeat revisionism in practice by developing militant struggles against the ruling class, not by polemics.

� Fighting the old “C”P would divert us from the outward focus of building a mass base and put us on a sectarian course.

� It will isolate us from a number of good people still in the old Party or who have recently left it.

These arguments actually took no issue with the content of the report, but completely focused on the question of “open polemics” and “publication.” Indeed most of the “oppositionists” said that they agreed with the document and that it would be useful for inner PLM study groups and classes – but they insisted “it should not be published.”

Why did these comrades fear publishing Road to Revolution even though they claimed that they agreed with it?

The real reason was this: The S.F. PLM leadership all came out of the old “C”P. Instead of integrating new young people that were attracted to PLM as a result of our revolutionary politics and militant national campaigns, they organized the new young forces into a separate PLM youth group. The leadership remained completely in the hands of ex-“C”P’ers who refused to break with their old “C”P friends and contacts. While they argued t that open polemics would set PLM on a sectarian course the truth is that they had oriented their political work primarily, to the old left and not towards winning new young revolutionists.

The “oppositionists” feared antagonizing their old pals who supported the revisionists and they also feared having to publicly defend communist political ideas against revisionist attacks. They judged the publication of Road to Revolution to be sectarian because their outlook was not to build a new revolutionary party with new cadres and a new mass base, but how to maintain their old relationships. As the letter from the PLM National Coordinating Committee stated in reply to the S.F. leadership: “Our major attention should not be placed on what our individual relations are with old “C”P members – on what they think of our ideas and actions at this moment or that moment. We cannot and will not evaluate our reports and work on that basis. If your line is right and if your work is positive and if you dare to fight imperialism and revisionism, then the possibility exists for winning the best of what remains in the old party.”

Actually it was the S.F. leadership that was on a sectarian path! They did not understand the necessity to publish Road to Revolution as a vital document in the fight to win new young fighters to communism because that was not their main focus.

The argument that only practice not polemics will defeat revisionism is a worn-out old dodge to avoid ideological struggle. Often in the history of the communist movement there have been attempts by various opportunists to pit theory, against practice and practice against theory. Of course revolutionary practice is primary in the workers’ struggle to defeat revisionism and the ruling class, for practice is the source of ideas. But practice without ideological struggle cannot win either because the outlook of workers helps determine their course of action.

The oppositionists’ position that words could not defeat revisionism was an echo of the old “CP’s attack on the Chinese Communist Party’s revolutionary propaganda as being nothing but “cardboard swords” “curses” and “vituperation that will not weaken imperialism.” The CPC correctly pointed out in their reply to the “C”P U.S.A. that “In the eyes of these persons, aren’t all revolutionary propaganda undertaken by Communists since the time of the Communist Manifesto, all the writings of Marx and Engels exposing capitalism, all Lenin’s works exposing imperialism ... aren’t they all only “cardboard swords”?

“These persons emphatically fail to understand that once the theory of Marxism-Leninism grips the masses of the people a tremendous material force is generated. Once armed with revolutionary ideas, the masses of the people will dare to struggle and to seize victory, and they will accomplish earth-shaking feats.”

The reply of the N.C.C. also made the following points to rebut the oppositionists’ arguments:

“It is true that at the outset we took the tact that we should not involve ourselves with too much debate about the old party. This still holds true. But we didn’t budge at the beginning. To do so then would have been a serious error. We had to use all our resources to get off the ground. Our political unity was yet to be tested. Our leadership had not yet developed as a collective. Accomplishments had to be made to prove that an alternative path was necessary and possible. However, growth, limited as it may be has imposed new conditions on us. First of all students, workers and others want to know the differences between us and the CP. in as much as we both call ourselves communists. There is much confusion on this score.

“Workers in Harlem, for example, are interested in the Sino-Soviet dispute. They are militantly pro-Chinese. These workers remember the old party. Their recollections are good and bad. They want to know our thinking on these questions, and how we are going to work in the present in a different way.

“MLQ goes out to two thousand readers. The next issue will be three thousand copies. Fortunately or unfortunately as the case may be we have arrived at the stage where it is impossible or desirable to answer these questions verbally. And even worse – to ignore them.

“Secondly, PL takes a critical position on the reformist leaders in the people’s movement. We attempt to analyze them all, and where possible to point out an alternative path. Can we ignore for all time the lessons to be learned from the history of the (old communist) movement, and the harmful role it plays today? In other words we can criticize all, but not the CP. leaders. What cowards we would be in the eyes of the advanced workers!

“Finally, revisionism is a set of harmful political ideas. They are put forward by specific people around specific issues. In order to benefit from history, a generally valid idea, you have to deal with actual occurrences. Historically that is how it was done. (We) doubt if that will ever change.

“Consequently, revisionism is not an abstraction. It is made up of live people with wrong ideas. The “C’P.’s main political enemy is us, and it does all in its power to destroy us. In this they work hand in glove with the (class) enemy who now view us as their main cross to bear.

“Each year the old party attracts and influences many students. As a result many young people become corrupted, cynical and useless to any political movement. Despite an earlier background of positive efforts, the “C.”P. revisionism has set back the (revolutionary) Marxist-Leninist movement in this country. As a matter of fact, the old party doesn’t simply follow a wrong line – it is involved in counter-revolutionary activity.

The S.F. oppositionists threatened to split if the document was published.

Naturally the PLM would not abandon the struggle against revisionism by such a threat. The NCC advised the oppositionists to review their commitment to the unity of the working class and to building its communist vanguard party and said “We do not see that ideological discussion combined with much practical work should create schism. If comrades allow themselves to be so easily derailed from building the movement over the question of how best to fight the common danger, revisionism, then this implies other questions.”

Unfortunately, the oppositionists did not heed the NCC’s advice. In January 1964, a special S.F. Bay Area meeting of all members and some friends of PLM and the PL youth group was convened in a final effort to resolve the struggle over the publication of Road to Revolution in a comradely fashion. PLP’s Vice-chairman, Mort Scheer, was sent to represent the NCC at the meeting. An intensive debate ensued.

Most of the comrades in the PLM youth group as well as several veteran Trade Union communists supported the NCC’s position. However, the oppositionists maintained a majority; almost all of whom were ex-CP.’ers. Nationally the S.F. oppositionist grouping represented only a small fraction of the PLM membership 90% of whom were new young revolutionists who had never been near the old “C.”P.

Following the January meeting the oppositionists quit PLM and tried to build a new group. It evaporated within a year.

The NCC followed up the January meeting by assigning Mort Scheer to be the West Coast organizer to assist the young comrades and trade union veterans who remained loyal to PLM to build the new communist organization in the S.F. Bay Area. While the oppositions soon disappeared the new PLM began to flourish as it did on the East Coast so that by the time of the founding convention of the Progressive Labor Party in 1965, the West Coast was an integral part of the new communist party.

Just as important lessons, were learned from our struggles in the mass movement, we also learned much from this and other inner-party struggles:

� The ruling class has always tried to portray communists as opponents of polemics and the public exchange of ideas, but the fact is that ideological struggle has always been a central feature of the communist movement and always will be. Indeed communist consciousness thrives on ideological struggle against its enemies and a communist movement grows stronger by purging its ranks of capitalist ideology. This has been the experience of the international communist movement and it has been the experience also in PL’s history.

� Another lesson in connection with the struggle around Road to Revolution is the question of loyalty. While loyalty to family and bid friends is often an admirable quality it must not supercede loyalty to the working people of the world. The sole test for communist policy and activity can only be this: Does it serve the revolutionary interests of the international workingclass?

� Revolutionaries cannot live in the past, but must always link up their lives with what is new and developing in the working class movement. The oppositionists were so tied up with the old communist movement that they could not and did not realize that the “C.”P. was dead as a revolutionary organization and had become counterrevolutionary.

� Splits are an inevitable part of the process of growth. The new casts off the old; the revolutionary discards and destroys the counter-revolutionary.

Dedicated communists, however, are deeply committed to the unity of the working class and will never split for petty reasons. We split away from enemies and will struggle to destroy them, but with friends and comrades we always strive for unity no matter how sharp our differences. While on the surface it appeared that Road to Revolution led to a minor split in PLM the reality is that it led to a much greater unity.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) led 25,000 people to Washington, D.C. on April 17, 1965 to protest U.S. involvement in the Vietnam war. This demonstration started a process which transformed the organization and led toward events such as the shutdown of Columbia University in 1968, San Francisco State 1968-1969 and Kent State strike in 1970. By the fall of 1966 thousands of college students had flooded into SDS, creating hundreds of new campus chapters.

Before 1965, the organization had been small, mainly confined to graduate students, and relatively unified around a liberal, anti-communist ideology. The new members joined because they felt the Vietnam war was unjust, that there were many related injustices in the U.S. society and that SDS, based on the April demonstration, was the place to do something about it. ACTION, perhaps in the image of the civil rights movement, was on their minds. ”Ideology” was generally distrusted, and looked down upon as a relic of the ”old left.” These students quickly discovered that their desire to fight back forced them to consider ideological questions, such as exactly why the United States was in Vietnam. These debates were vital precisely because they helped determine what to do and how to do it, a far cry from the empty ”theoretical” arguments they rejected.

As noted in Part III of the History of the PLP, the students in the Progressive Labor Movement took a day off from the Party’s founding convention and joined the April 1965 demonstration in Washington. Together with our comrades in the May Second Movement (M2M) we brought hundreds to Washington and put forward the line of “U.S. Get Out of Vietnam Now,” which was enthusiastically adopted by thousands of demonstrators. Sometime later, in the winter of 1965-1966, we won the majority of the M2M members to dissolving that organization and joining SDS. We realized that most of the students who were joining SDS to actively oppose the war did not have an anti-imperialist outlook, and to learn from them at the same time, we had to be where they were – in SDS.

During the period 1966-1968, PLP’s main form of political organizing among masses of students was in SDS. There we sold CHALLENGE-DESAFIO, issued Party leaflets, and conducted some activities under our direct leadership. Some of these activities were conducted in alliance with SDS and/or other campus organizations.

Both independently and within SDS, PLPers helped provide leadership to many of the most militant and massive campus struggles of this period, as well as numerous smaller ones. These included fighting against ROTC, campus recruiters for the military services and the Dow Chemical Co. (makers of napalm), against university sponsored research for the Vietnam war, and against class ranking for the draft. Among other schools, these struggles took place at Fordham, CCNY, Brooklyn College, Queens College, all in N.Y.; Harvard, Boston College, Boston University, Princeton, Rutgers, Stonybrook, Univ. of Chicago, Michigan State, Iowa State, Berkeley, Stanford, and San Francisco State.

SDS was able to lead these struggles because of an ideological struggle that was carried on simultaneously within the organization. We in PL and others fought against the ideas that the U.S. was in Vietnam through some sort of mistake, and that troops remained there through the stubbornness of the military, LBJ, or Nixon. We pointed out that the U.S. government had financed France’s war to hold onto Vietnam and her other Indo-Chinese colonies in the 1950’s, and that the motives for the U.S. war on Vietnam of the 1960’s were no different – to keep the profits rolling in. We explained the necessity of investment in areas where labor is available at super-low wages for the survival of monopoly capitalism. We argued that the government was an instrument of the capitalist class, and that the so-called “doves” differed with the “hawks” only on the right tactics for holding onto Vietnam and exploiting the Vietnamese people. After all, the foremost “dove” of all, John Kennedy, had played a major role in starting the war. His only “mistake” had been underestimating the capacity of the Vietnamese people to fight back.

To this analysis we added the idea that the administrations of our universities were servants of the capitalist class, and were helping in countless ways to wage the war. As students, we were in a perfect position to expose this (many of these college presidents and deans were super-liberal “opponents” of the war) and fight against it, bringing the anti-war movement home to thousands of our classmates who would, otherwise, not have become involved. Where they did become involved, leading to massive confrontations and shut-down campuses, millions more people around the country became conscious of the anti-war movement via the news media.