Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1904

Source: "Fables for Children," by Leo Tolstoy, translated from the original Russian and edited by leo Wiener, assistant Professor of Slavic Languages at Harvard University, published by Dana Estese Company, Boston, Edition De Luxe, limited to one thousand copies of which this is no. 411, copyright 1904, electrotyped and printed by C. H. Simonds and Co., Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

A certain gentleman was serving as an officer in the Caucasus. His name was Zhilín.

One day he received a letter from home. His old mother wrote to him:

"I have grown old, and I should like to see my darling son before my death. Come to bid me farewell and bury me, and then, with God's aid, return to the service. I have also found a bride for you: she is bright and pretty and has property. If you take a liking to her, you can marry her, and stay here for good."

Zhilín reflected: "Indeed, my old mother has grown feeble; perhaps I shall never see her again. I must go; and if the bride is a good girl, I may marry her."

He went to the colonel, got a furlough, bade his companions good-bye, treated his soldiers to four buckets of vódka, and got himself ready to go.

At that time there was a war in the Caucasus. Neither in the daytime, nor at night, was it safe to travel on the roads. The moment a Russian walked or drove away from a fortress, the Tartars either killed him or took him as a prisoner to the mountains. It was a rule that a guard of soldiers should go twice a week from fortress to fortress. In front and in the rear walked soldiers, and between them were other people.

It was in the summer. The carts gathered at daybreak outside the fortress, and the soldiers of the convoy came out, and all started. Zhilín rode on horseback, and his cart with his things went with the caravan.

They had to travel twenty-five versts. The caravan proceeded slowly; now the soldiers stopped, and now a wheel came off a cart, or a horse stopped, and all had to stand still and wait.

The sun had already passed midday, but the caravan had made only half the distance. It was dusty and hot; the sun just roasted them, and there was no shelter: it was a barren plain, with neither tree nor bush along the road.

Zhilín rode out ahead. He stopped and waited for the caravan to catch up with him. He heard them blow the signal-horn behind: they had stopped again.

Zhilín thought: "Why can't I ride on, without the soldiers? I have a good horse under me, and if I run against Tartars, I will gallop away. Or had I better not go?"

He stopped to think it over. There rode up to him another officer, Kostylín, with a gun, and said:

"Let us ride by ourselves, Zhilín! I cannot stand it any longer: I am hungry, and it is so hot. My shirt is dripping wet."

Kostylín was a heavy, stout man, with a red face, and the perspiration was just rolling down his face. Zhilín thought awhile and said:

"Is your gun loaded?"

"It is."

"Well, then, we will go, but on one condition, that we do not separate."

And so they rode ahead on the highway. They rode through the steppe, and talked, and looked about them. They could see a long way off.

When the steppe came to an end, the road entered a cleft between two mountains. So Zhilín said:

"We ought to ride up the mountain to take a look; for here they may leap out on us from the mountain without our seeing them."

But Kostylín said:

"What is the use of looking? Let us ride on!"

Zhilín paid no attention to him.

"No," he said, "you wait here below, and I will take a look up there."

And he turned his horse to the left, up-hill. The horse under Zhilín was a thoroughbred (he had paid a hundred rubles for it when it was a colt, and had himself trained it), and it carried him up the slope as though on wings. The moment he reached the summit, he saw before him a number of Tartars on horseback, about eighty fathoms away. There were about thirty of them. When he saw them, he began to turn back; and the Tartars saw him, and galloped toward him, and on the ride took their guns out of the covers. Zhilín urged his horse down-hill as fast as its legs would carry him, and he shouted to Kostylín:

"Take out the gun!" and he himself thought about his horse: "Darling, take me away from here! Don't stumble! If you do, I am lost. If I get to the gun, they shall not catch me."

But Kostylín, instead of waiting, galloped at full speed toward the fortress, the moment he saw the Tartars. He urged the horse on with the whip, now on one side, and now on the other. One could see through the dust only the horse switching her tail.

Zhilín saw that things were bad. The gun had disappeared, and he could do nothing with a sword. He turned his horse back to the soldiers, thinking that he might get away. He saw six men crossing his path. He had a good horse under him, but theirs were better still, and they crossed his path. He began to check his horse: he wanted to turn around; but the horse was running at full speed and could not be stopped, and he flew straight toward them. He saw a red-bearded Tartar on a gray horse, who was coming near to him. He howled and showed his teeth, and his gun was against his shoulder.

"Well," thought Zhilín, "I know you devils. When you take one alive, you put him in a hole and beat him with a whip. I will not fall into your hands alive——"

Though Zhilín was not tall, he was brave. He drew his sword, turned his horse straight against the Tartar, and thought:

"Either I will knock his horse off its feet, or I will strike the Tartar with my sword."

Zhilín got within a horse's length from him, when they shot at him from behind and hit the horse. The horse dropped on the ground while going at full speed, and fell on Zhilín's leg.

He wanted to get up, but two stinking Tartars were already astride of him. He tugged and knocked down the two Tartars, but three more jumped down from their horses and began to strike him with the butts of their guns. Things grew dim before his eyes, and he tottered. The Tartars took hold of him, took from their saddles some reserve straps, twisted his arms behind his back, tied them with a Tartar knot, and fastened him to the saddle. They knocked down his hat, pulled off his boots, rummaged all over him, and took away his money and his watch, and tore all his clothes.

Zhilín looked back at his horse. The dear animal was lying just as it had fallen down, and only twitched its legs and did not reach the ground with them; in its head there was a hole, and from it the black blood gushed and wet the dust for an ell around.

A Tartar went up to the horse, to pull off the saddle. The horse was struggling still, and so he took out his dagger and cut its throat. A whistling sound came from the throat, and the horse twitched, and was dead.

The Tartars took off the saddle and the trappings. The red-bearded Tartar mounted his horse, and the others seated Zhilín behind him. To prevent his falling off, they attached him by a strap to the Tartar's belt, and they rode off to the mountains.

Zhilín was sitting back of the Tartar, and shaking and striking with his face against the stinking Tartar's back. All he saw before him was the mighty back, and the muscular neck, and the livid, shaved nape of his head underneath his cap. Zhilín's head was bruised, and the blood was clotted under his eyes. And he could not straighten himself on the saddle, nor wipe off his blood. His arms were twisted so badly that his shoulder bones pained him.

They rode for a long time from one mountain to another, and forded a river, and came out on a path, where they rode through a ravine.

Zhilín wanted to take note of the road on which they were traveling, but his eyes were smeared with blood, and he could not turn around.

It was getting dark. They crossed another stream and rode up a rocky mountain. There was an odor of smoke, and the dogs began to bark. They had come to a native village. The Tartars got down from their horses; the Tartar children gathered around Zhilín, and screamed, and rejoiced, and aimed stones at him.

The Tartar drove the boys away, took Zhilín down from his horse, and called a laborer. There came a Nogay, with large cheek-bones; he wore nothing but a shirt. The shirt was torn and left his breast bare. The Tartar gave him a command. The laborer brought the stocks,—two oak planks drawn through iron rings, and one of these rings with a clasp and lock.

They untied Zhilín's hands, put the stocks on him, and led him into a shed: they pushed him in and locked the door. Zhilín fell on the manure pile. He felt around in the darkness for a soft spot, and lay down there.

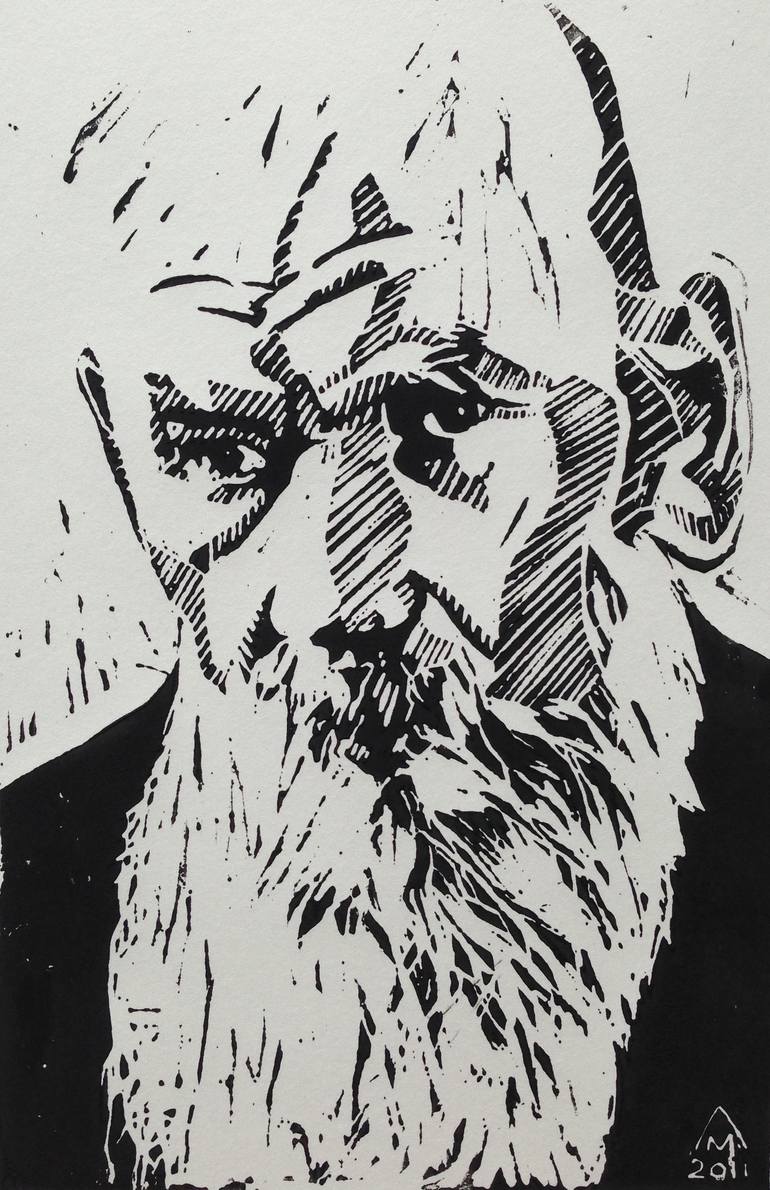

"They rode off to the mountains"

Photogravure from Painting by A. Kivshénko

Zhilín lay awake nearly the whole night. The nights were short. He saw through a chink that it was getting light. He got up, made the chink larger, and looked out.

Through the chink Zhilín saw the road: it went down-hill; on the right was a Tartar cabin, and near it two trees. A black dog lay on the threshold, and a goat strutted about with her kids, which were jerking their little tails. He saw a young Tartar woman coming up the hill; she wore a loose colored shirt and pantaloons and boots, and her head was covered with a caftan, and on her head there was a large tin pitcher with water. She walked along, jerking her back, and bending over, and by the hand she led a young shaven Tartar boy in nothing but his shirt. The Tartar woman went into the cabin with the water, and out came the Tartar of the day before, with the red beard, wearing a silk half-coat, a silver dagger on a strap, and shoes on his bare feet. On his head there was a tall, black sheepskin hat, tilted backwards. He came out, and he stretched himself and smoothed his red beard. He stood awhile, gave the laborer an order, and went away.

Then two boys rode by, taking the horses to water. The muzzles of the horses were wet. Then there ran out some other shaven boys, in nothing but their shirts, with no trousers; they gathered in a crowd, walked over to the shed, picked up a stick, and began to poke it through the chink. When Zhilín shouted at the children, they screamed and started to run back, so that their bare knees glistened in the sun.

Zhilín wanted to drink,—his throat was all dried up. He thought: "If they would only come to see me!" He heard them open the shed. The red Tartar came in, and with him another, black-looking fellow, of smaller stature. His eyes were black and bright, his cheeks ruddy, his small beard clipped; his face looked jolly, and he kept laughing all the time. This swarthy fellow was dressed even better: he had on a silk half-coat, of a blue color, embroidered with galloons. In his belt there was a large silver dagger; his slippers were of red morocco and also embroidered with silver. Over his thin slippers he wore heavier shoes. His cap was tall, of white astrakhan.

The red Tartar came in. He said something, as though scolding, and stopped. He leaned against the door-post, dangled his dagger, and like a wolf looked furtively at Zhilín. But the swarthy fellow—swift, lively, walking around as though on springs—went up straight to Zhilín, squatted down, showed his teeth, slapped him on the shoulder, began to rattle off something in his language, winked with his eyes, clicked his tongue, and kept repeating: "Goot Uruss! Goot Uruss!"

Zhilín did not understand a thing and said:

"Give me to drink, give me water to drink!"

The swarthy fellow laughed. "Goot Uruss!" he kept rattling off.

Zhilín showed with his lips and hands that he wanted something to drink.

The swarthy fellow understood what he wanted, laughed out, looked through the door, and called some one: "Dina!"

In came a thin, slender little girl, of about thirteen years of age, who resembled the swarthy man very much. Evidently she was his daughter. Her eyes, too, were black and bright, and her face was pretty. She wore a long blue shirt, with broad sleeves and without a belt. The skirt, the breast, and the sleeves were trimmed with red. On her legs were pantaloons, and on her feet slippers, with high-heeled shoes over them; on her neck she wore a necklace of Russian half-rubles. Her head was uncovered; her braid was black, with a ribbon through it, and from the ribbon hung small plates and a Russian ruble.

Her father gave her a command. She ran away, and came back and brought a small tin pitcher. She gave him the water, and herself squatted down, bending up in such a way that her shoulders were below her knees. She sat there, and opened her eyes, and looked at Zhilín drinking, as though he were some animal.

Zhilín handed her back the pitcher. She jumped away like a wild goat. Even her father laughed. He sent her somewhere else. She took the pitcher and ran away; she brought some fresh bread on a round board, and again sat down, bent over, riveted her eyes on him, and kept looking.

The Tartars went away and locked the door.

After awhile the Nogay came to Zhilín, and said:

"Ai-da, master, ai-da!"

He did not know any Russian, either. All Zhilín could make out was that he should follow him.

Zhilín started with the stocks, and he limped and could not walk, so much did the stocks pull his legs aside. Zhilín went out with the Nogay. He saw a Tartar village of about ten houses, and a church of theirs, with a small tower. Near one house stood three horses, all saddled. Boys were holding the reins. From the house sprang the swarthy Tartar, and he waved his hand for Zhilín to come up. He laughed all the while, and talked in his language, and disappeared through the door.

Zhilín entered the house. It was a good living-room,—the walls were plastered smooth with clay. Along the front wall lay colored cushions, and at the sides hung costly rugs; on the rugs were guns, pistols, swords,—all in silver. By one wall there was a small stove, on a level with the floor. The floor was of dirt and as clean as a threshing-floor, and the whole front corner was carpeted with felt; and over the felt lay rugs, and on the rugs cushions. On these rugs sat the Tartars, in their slippers without their outer shoes: there were the swarthy fellow, the red Tartar, and three guests. At their backs were feather cushions, and before them, on a round board, were millet cakes and melted butter in a bowl, and Tartar beer, "buza," in a small pitcher. They were eating with their hands, and their hands were all greasy from the butter.

The swarthy man jumped up and ordered Zhilín to be placed to one side, not on a rug, but on the bare floor; he went back to his rug, and treated his guests to millet cakes and buza. The laborer placed Zhilín where he had been ordered, himself took off his outer shoes, put them at the door, where stood the other shoes, and sat down on the felt next to the masters. He looked at them as they ate, and wiped off his spittle.

The Tartars ate the cakes. Then there came a Tartar woman, in a shirt like the one the girl had on, and in pantaloons, and with a kerchief over her head. She carried away the butter and the cakes, and brought a small wash-basin of a pretty shape, and a pitcher with a narrow neck. The Tartars washed their hands, then folded them, knelt down, blew in every direction, and said their prayers. Then one of the Tartar guests turned to Zhilín, and began to speak in Russian:

"You," he said, "were taken by Kazi-Muhammed," and he pointed to the red Tartar, "and he gave you to Abdul-Murat." He pointed to the swarthy man. "Abdul-Murat is now your master."

Zhilín kept silence. Then Abdul-Murat began to speak. He pointed to Zhilín, and laughed, and kept repeating:

"Soldier Uruss! Goot Uruss!"

The interpreter said:

"He wants you to write a letter home that they may send a ransom for you. When they send it, you will be set free."

Zhilín thought awhile and said:

"How much ransom does he want?"

The Tartars talked together; then the interpreter said:

"Three thousand in silver."

"No," said Zhilín, "I cannot pay that."

Abdul jumped up, began to wave his hands and to talk to Zhilín, thinking that he would understand him. The interpreter translated. He said:

"How much will you give?"

Zhilín thought awhile, and said:

"Five hundred rubles."

Then the Tartars began to talk a great deal, all at the same time. Abdul shouted at the red Tartar. He was so excited that the spittle just spirted from his mouth.

But the red Tartar only scowled and clicked his tongue.

They grew silent, and the interpreter said:

"The master is not satisfied with five hundred rubles. He has himself paid two hundred for you. Kazi-Muhammed owed him a debt. He took you for that debt. Three thousand rubles, nothing less will do. And if you do not write, you will be put in a hole and beaten with a whip."

"Oh," thought Zhilín, "it will not do to show that I am frightened; that will only be worse." He leaped to his feet, and said:

"Tell that dog that if he is going to frighten me, I will not give him a penny, and I will refuse to write. I have never been afraid of you dogs, and I never will be."

The interpreter translated, and all began to speak at the same time.

They babbled for a long time; then the swarthy Tartar jumped up and walked over to Zhilín:

"Uruss," he said, "dzhigit, dzhigit Uruss!"

Dzhigit in their language means a "brave." And he laughed; he said something to the interpreter, and the interpreter said:

"Give one thousand rubles!"

Zhilín stuck to what he had said:

"I will not give more than five hundred. And if you kill me, you will get nothing."

The Tartars talked awhile and sent the laborer somewhere, and themselves kept looking now at Zhilín and now at the door. The laborer came, and behind him walked a fat man; he was barefoot and tattered; he, too, had on the stocks.

Zhilín just shouted, for he recognized Kostylín. He, too, had been caught. They were placed beside each other. They began to talk to each other, and the Tartars kept silence and looked at them. Zhilín told what had happened to him; and Kostylín told him that his horse had stopped and his gun had missed fire, and that the same Abdul had overtaken and captured him.

Abdul jumped up, and pointed to Kostylín, and said something. The interpreter translated it, and said that both of them belonged to the same master, and that the one who would first furnish the money would be the first to be released.

"Now you," he said, "are a cross fellow, but your friend is meek; he has written a letter home, and they will send five thousand rubles. He will be fed well, and will not be insulted."

So Zhilín said:

"My friend may do as he pleases; maybe he is rich, but I am not. As I have said, so will it be. If you want to, kill me,—you will not gain by it,—but more than five hundred will I not give."

They were silent for awhile. Suddenly Abdul jumped up, fetched a small box, took out a pen, a piece of paper, and some ink, put it all before Zhilín, slapped him on the shoulder, and motioned for him to write. He agreed to the five hundred.

"Wait awhile," Zhilín said to the interpreter. "Tell him that he has to feed us well, and give us the proper clothes and shoes, and keep us together,—it will be jollier for us,—and take off the stocks." He looked at the master and laughed. The master himself laughed. He listened to the interpreter, and said:

"I will give you the best of clothes,—a Circassian mantle and boots,—you will be fit to marry. We will feed you like princes. And if you want to stay together, you may live in the shed. But the stocks cannot be taken off, for you will run away. For the night we will take them off."

He ran up to Zhilín, and tapped him on the shoulder:

"You goot, me goot!"

Zhilín wrote the letter, but he did not address it right. He thought he would run away.

Zhilín and Kostylín were taken back to the shed. They brought for them maize straw, water in a pitcher, bread, two old mantles, and worn soldier boots. They had evidently been pulled off dead soldiers. For the night the stocks were taken off, and they were locked in the barn.

Zhilín and his companion lived thus for a whole month. Their master kept laughing.

"You, Iván, goot, me, Abdul, goot!"

But he did not feed them well. All he gave them to eat was unsalted millet bread, baked like pones, or entirely unbaked dough.

Kostylín wrote home a second letter. He was waiting for the money to come, and felt lonesome. He sat for days at a time in the shed counting the days before the letter would come, or he slept. But Zhilín knew that his letter would not reach any one, and so he did not write another.

"Where," he thought, "is my mother to get so much money? As it is, she lived mainly by what I sent her. If she should collect five hundred rubles, she would be ruined in the end. If God grants it, I will manage to get away from here."

And he watched and thought of how to get away.

He walked through the village and whistled, or he sat down somewhere to work with his hands, either making a doll from clay, or weaving a fence from twigs. Zhilín was a great hand at all kinds of such work.

One day he made a doll, with a nose, and hands, and legs, in a Tartar shirt, and put the doll on the roof. The Tartar maidens were going for water. His master's daughter, Dina, saw the doll, and she called up the Tartar girls. They put down their pitchers, and looked, and laughed. Zhilín took down the doll and gave it to them. They laughed, and did not dare take it. He left the doll, and went back to the shed to see what they would do.

Dina ran up, looked around, grasped the doll, and ran away with it.

In the morning, at daybreak, he saw Dina coming out with the doll in front of the house. The doll was all dressed up in red rags, and she was rocking the doll and singing to it in her fashion. The old woman came out. She scolded her, took the doll away from her and broke it, and sent Dina to work.

Zhilín made another doll, a better one than before, and he gave it to Dina. One day Dina brought him a small pitcher. She put it down, herself sat down and looked at him, and laughed, as she pointed to the pitcher.

"What is she so happy about?" thought Zhilín.

He took the pitcher and began to drink. He thought it was water, but, behold, it was milk. He drank the milk, and said:

"It is good!"

Dina was very happy.

"Good, Iván, good!" and she jumped up, clapped her hands, took away the pitcher, and ran off.

From that time she brought him milk every day on the sly. The Tartars make cheese-cakes from goat milk, and dry them on the roofs,—and so she brought him those cakes also. One day the master killed a sheep, so she brought him a piece of mutton in her sleeve. She would throw it down and run away.

One day there was a severe storm, and for an hour the rain fell as though from a pail. All the streams became turbid. Where there was a ford, the water was now eight feet deep, and stones were borne down. Torrents were running everywhere, and there was a roar in the mountains. When the storm was over, streams were coming down the village in every direction. Zhilín asked his master to let him have a penknife, and with it he cut out a small axle and little boards, and made a wheel, and to each end of the wheel he attached a doll.

The girls brought him pieces of material, and he dressed the dolls: one a man, the other a woman. He fixed them firmly, and placed the wheel over a brook. The wheel began to turn, and the dolls to jump.

The whole village gathered around it; boys, girls, women, and men came, and they clicked with their tongues:

"Ai, Uruss! Ai, Iván!"

Abdul had a Russian watch, but it was broken. He called Zhilín, showed it to him, and clicked his tongue. Zhilín said:

"Let me have it! I will fix it!"

He took it to pieces with a penknife; then he put it together, and gave it back to him. The watch was running now.

The master was delighted. He brought his old half-coat,—it was all in rags,—and made him a present of it. What could he do but take it? He thought it would be good enough to cover himself with in the night.

After that the rumor went abroad that Zhilín was a great master. They began to come to him from distant villages: one, to have him fix a gun-lock or a pistol, another, to set a clock a-going. His master brought him tools,—pinchers, gimlets, and files.

One day a Tartar became sick: they sent to Zhilín, and said, "Go and cure him!" Zhilín did not know anything about medicine. He went, took a look at him, and thought, "Maybe he will get well by himself." He went to the barn, took some water and sand, and mixed it. In the presence of the Tartars he said a charm over the water, and gave it to him to drink. Luckily for him, the Tartar got well.

Zhilín began to understand their language. Some of the Tartars got used to him. When they needed him, they called, "Iván, Iván!" but others looked at him awry, as at an animal.

The red Tartar did not like Zhilín. Whenever he saw him, he frowned and turned away, or called him names. There was also an old man; he did not live in the village, but came from farther down the mountain. Zhilín saw him only when he came to the mosque, to pray to God. He was a small man; his cap was wrapped with a white towel. His beard and mustache were clipped, and they were as white as down; his face was wrinkled and as red as a brick. His nose was hooked, like a hawk's beak, and his eyes were gray and mean-looking; of teeth he had only two tusks. He used to walk in his turban, leaning on a crutch, and looking around him like a wolf. Whenever he saw Zhilín, he grunted and turned away.

One day Zhilín went down-hill, to see where the old man was living. He walked down the road, and saw a little garden, with a stone fence, and inside the fence were cherry and apricot trees, and stood a hut with a flat roof. He came closer to it, and he saw beehives woven from straw, and bees were swarming around and buzzing. The old man was kneeling, and doing something to a hive. Zhilín got up higher, to get a good look, and made a noise with his stocks. The old man looked around and shrieked; he pulled the pistol out from his belt and fired at Zhilín. He had just time to hide behind a rock.

The old man went to the master to complain about Zhilín. The master called up Zhilín, and laughed, and asked:

"Why did you go to the old man?"

"I have not done him any harm," he said. "I just wanted to see how he lives."

The master told the old man that. But the old man was angry, and hissed, and rattled something off; he showed his teeth and waved his hand threateningly at Zhilín.

Zhilín did not understand it all; but he understood that the old man was telling his master to kill all the Russians, and not to keep them in the village. The old man went away.

Zhilín asked his master what kind of a man that old Tartar was. The master said:

"He is a big man! He used to be the first dzhigit: he killed a lot of Russians, and he was rich. He had three wives and eight sons. All of them lived in the same village. The Russians came, destroyed the village, and killed seven of his sons. One son was left alive, and he surrendered himself to the Russians. The old man went and surrendered himself, too, to the Russians. He stayed with them three months, found his son there, and killed him, and then he ran away. Since then he has stopped fighting. He has been to Mecca, to pray to God, and that is why he wears the turban. He who has been to Mecca is called a Hajji and puts on a turban. He has no use for you fellows. He tells me to kill you; but I cannot kill you,—I have paid for you; and then, Iván, I like you. I not only have no intention of killing you, but I would not let you go back, if I had not given my word to you." He laughed as he said that, and added in Russian: "You, Iván, good, me, Abdul, good!"

Zhilín lived thus for a month. In the daytime he walked around the village and made things with his hands, and when night came, and all was quiet in the village, he began to dig in the shed. It was difficult to dig on account of the rocks, but he sawed the stones with the file, and made a hole through which he meant to crawl later. "First I must find out what direction to go in," he thought; "but the Tartars will not tell me anything."

So he chose a time when his master was away; he went after dinner back of the village, up-hill, where he could see the place. But when his master went away, he told his little boy to keep an eye on Zhilín and to follow him everywhere. So the boy ran after Zhilín, and said:

"Don't go! Father said that you should not go there. I will call the people!"

Zhilín began to persuade him.

"I do not want to go far," he said; "I just want to walk up the mountain: I want to find an herb with which to cure you people. Come with me; I cannot run away with the stocks. Tomorrow I will make you a bow and arrows."

He persuaded the boy, and they went together. As he looked up the mountain, it looked near, but with the stocks it was hard to walk; he walked and walked, and climbed the mountain with difficulty. Zhilín sat down and began to look at the place. To the south of the shed there was a ravine, and there a herd of horses was grazing, and in a hollow could be seen another village. At that village began a steeper mountain, and beyond that mountain there was another mountain. Between the mountains could be seen a forest, and beyond it again the mountains, rising higher and higher. Highest of all, there were white mountains, capped with snow, just like sugar loaves. And one snow mountain stood with its cap above all the rest. To the east and the west there were just such mountains; here and there smoke rose from villages in the clefts.

"Well," he thought, "that is all their side."

He began to look to the Russian side. At his feet was a brook and his village, and all around were little gardens. At the brook women were sitting,—they looked as small as dolls,—and washing the linen. Beyond the village and below it there was a mountain, and beyond that, two other mountains, covered with forests; between the two mountains could be seen an even spot, and on that plain, far, far away, it looked as though smoke were settling. Zhilín recalled where the sun used to rise and set when he was at home in the fortress. He looked down there,—sure enough, that was the valley where the Russian fortress ought to be. There, then, between those two mountains, he had to run.

The sun was beginning to go down. The snow-capped mountains changed from white to violet; it grew dark in the black mountains; vapor arose from the clefts, and the valley, where our fortress no doubt was, gleamed in the sunset as though on fire. Zhilín began to look sharply,—something was quivering in the valley, like smoke rising from chimneys. He was sure now that it must be the Russian fortress.

It grew late; he could hear the mullah call; the flock was being driven, and the cows lowed. The boy said to him, "Come!" but Zhilín did not feel like leaving.

They returned home. "Well," thought Zhilín, "now I know the place, and I must run." He wanted to run that same night. The nights were dark,—the moon was on the wane. Unfortunately the Tartars returned toward evening. At other times they returned driving cattle before them, and then they were jolly. But this time they did not drive home anything, but brought back a dead Tartar, a red-haired companion of theirs. They came back angry, and all gathered to bury him. Zhilín, too, went out to see. They wrapped the dead man in linen, without putting him in a coffin, and carried him under the plane-trees beyond the village, and placed him on the grass. The mullah came, and the old men gathered around him, their caps wrapped with towels, and took off their shoes and seated themselves in a row on their heels, in front of the dead man.

At their head was the mullah, and then three old men in turbans, sitting in a row, and behind them other Tartars. They sat, and bent their heads, and kept silence. They were silent for quite awhile. Then the mullah raised his head, and said:

"Allah!" (That means "God.") He said that one word, and again they lowered their heads and kept silence for a long time; they sat without stirring. Again the mullah raised his head:

"Allah!" and all repeated, "Allah!" and again they were silent. The dead man lay on the grass, and did not stir, and they sat about him like the dead. Not one of them stirred. One could hear only the leaves on the plane-tree rustling in the breeze. Then the mullah said a prayer, and all got up, lifted the dead body, and carried it away. They took it to a grave,—not a simple grave, but dug under like a cave. They took the dead man under his arms and by his legs, bent him over, let him down softly, pushed him under in a sitting posture, and fixed his arms on his body.

A Nogay dragged up a lot of green reeds; they bedded the grave with it, then quickly filled it with dirt, leveled it up, and put a stone up straight at the head of it. They tramped down the earth, and again sat down in a row near the grave. They were silent for a long time.

"Allah, Allah, Allah!" They sighed and got up.

A red-haired Tartar distributed money to the old men; then he got up, took a whip, struck himself three times on his forehead, and went home.

Next morning Zhilín saw the red Tartar take a mare out of the village, and three Tartars followed him. They went outside the village; then the red-haired Tartar took off his coat, rolled up his sleeves,—he had immense arms,—and took out his dagger and whetted it on a steel. The Tartars jerked up the mare's head, and the red-haired man walked over to her, cut her throat, threw her down, and began to flay her,—to rip the skin open with his fists. Then came women and girls, and they began to wash the inside and the entrails. Then they chopped up the mare and dragged the flesh to the house. And the whole village gathered at the house of the red-haired Tartar to celebrate the dead man's wake.

For three days did they eat the horse-flesh, drink buza, and remember the dead man. On the fourth day Zhilín saw them get ready to go somewhere for a dinner. They brought horses, dressed themselves up, and went away,—about ten men, and the red Tartar with them; Abdul was the only one who was left at home. The moon was just beginning to increase, and the nights were still dark.

"Well," thought Zhilín, "to-night I must run," and he told Kostylín so. But Kostylín was timid.

"How can we run? We do not know the road."

"I know it."

"But we cannot reach it in the night."

"If we do not, we shall stay for the night in the woods. I have a lot of cakes with me. You certainly do not mean to stay. It would be all right if they sent the money; but suppose they cannot get together so much. The Tartars are mean now, because the Russians have killed one of theirs. I understand they want to kill us now."

Kostylín thought awhile:

"Well, let us go!"

Zhilín crept into the hole and dug it wider, so that Kostylín could get through; and then they sat still and waited for everything to quiet down in the village.

When all grew quiet, Zhilín crawled through the hole and got out. He whispered to Kostylín to crawl out. Kostylín started to come out, but he caught a stone with his foot, and it made a noise. Now their master had a dappled watch-dog, and he was dreadfully mean; his name was Ulyashin. Zhilín had been feeding him before. When Ulyashin heard the voice, he began to bark and rushed forward, and with him other dogs. Zhilín gave a low whistle and threw a piece of cake to the dog, and the dog recognized him and wagged his tail and stopped barking.

The master heard it, and he called out from the hut, "Hait, hait, Ulyashin!"

But Zhilín was scratching Ulyashin behind his ears; so the dog was silent and rubbed against his legs and wagged his tail.

They sat awhile around the corner. All was silent; nothing could be heard but the sheep coughing in the hut corner, and the water rippling down the pebbles. It was dark; the stars stood high in the heaven; the young moon shone red above the mountain, and its horns were turned upward. In the clefts the mist looked as white as milk.

Zhilín got up and said to his companion:

"Now, my friend, let us start!"

They started. They had made but a few steps, when they heard the mullah sing out on the roof: "Allah besmillah! Ilrakhman!" That meant that the people were going to the mosque. They sat down again, hiding behind a wall. They sat for a long time, waiting for the people to pass by. Again everything was quiet.

"Well, with God's aid!" They made the sign of the cross, and started. They crossed the yard and went down-hill to the brook; they crossed the brook and walked down the ravine. The mist was dense and low on the ground, and overhead the stars were, oh, so visible. Zhilín saw by the stars in what direction they had to go. In the mist it felt fresh, and it was easy to walk, only the boots were awkward, they had worn down so much. Zhilín took off his boots and threw them away, and marched on barefoot. He leaped from stone to stone, and kept watching the stars. Kostylín began to fall behind.

"Walk slower," he said. "The accursed boots,—they have chafed my feet."

"Take them off! You will find it easier without them."

Kostylín walked barefoot after that; but it was only worse: he cut his feet on the rocks, and kept falling behind. Zhilín said to him:

"If you bruise your feet, they will heal up; but if they catch you; they will kill you,—so it will be worse."

Kostylín said nothing, but he groaned as he walked. They walked for a long time through a ravine. Suddenly they heard dogs barking. Zhilín stopped and looked around; he groped with his hands and climbed a hill.

"Oh," he said, "we have made a mistake,—we have borne too much to the right. Here is a village,—I saw it from the mountain; we must go back and to the left, and up the mountain. There must be a forest here."

But Kostylín said:

"Wait at least awhile! Let me rest: my feet are all blood-stained."

"Never mind, friend, they will heal up! Jump more lightly,—like this!"

And Zhilín ran back, and to the left, up the mountain into the forest. Kostylín kept falling behind and groaning. Zhilín hushed him, and walked on.

They got up the mountain, and there, indeed, was a forest. They went into the forest, and tore all the clothes they had against the thorns. They struck a path in the forest, and followed it.

"Stop!" Hoofs were heard tramping on the path. They stopped to listen. It was the sound of a horse's hoofs. They started, and again it began to thud. They stopped, and it, too, stopped. Zhilín crawled up to it, and saw something standing in the light on the road. It was not exactly a horse, and again it was like a horse with something strange above it, and certainly not a man. He heard it snort. "What in the world is it?" Zhilín gave a light whistle, and it bolted away from the path, so that he could hear it crash through the woods: the branches broke off, as though a storm went through them.

Kostylín fell down in fright. But Zhilín laughed and said:

"That is a stag. Do you hear him break the branches with his horns? We are afraid of him, and he is afraid of us."

They walked on. The Pleiades were beginning to settle,—it was not far from morning. They did not know whether they were going right, or not. Zhilín thought that that was the path over which they had taken him, and that he was about ten versts from his own people; still there were no certain signs, and, besides, in the night nothing could be made out. They came out on a clearing. Kostylín sat down, and said:

"Do as you please, but I will not go any farther! My feet refuse to move."

Zhilín begged him to go on.

"No," he said, "I cannot walk on."

Zhilín got angry, spit out in disgust, and scolded him.

"Then I will go by myself,—good-bye!"

Kostylín got up and walked on. They walked about four versts. The mist grew denser in the forest, and nothing could be seen in front of them, and the stars were quite dim.

Suddenly they heard a horse tramping in front of them. They could hear the horse catch with its hoofs in the stones. Zhilín lay down on his belly, and put his ear to the ground to listen.

"So it is, a rider is coming this way!"

They ran off the road, sat down in the bushes, and waited. Zhilín crept up to the road, and saw a Tartar on horseback, driving a cow before him, and mumbling something to himself. The Tartar passed by them. Zhilín went back to Kostylín.

"Well, with God's help, he is gone. Get up, and let us go!"

Kostylín tried to get up, but fell down.

"I cannot, upon my word, I cannot. I have no strength."

The heavy, puffed-up man was in a perspiration, and as the cold mist in the forest went through him and his feet were all torn, he went all to pieces. Zhilín tried to get him up, but Kostylín cried:

"Oh, it hurts!"

Zhilín was frightened.

"Don't shout so! You know that the Tartar is not far off,—he will hear you." But he thought: "He is, indeed, weak, so what shall I do with him? It will not do to abandon my companion."

"Well," he said, "get up, get on my back, and I will carry you, if you cannot walk."

He took Kostylín on his back, put his hands on Kostylín's legs, walked out on the road, and walked on.

"Only be sure," he said, "and do not choke me with your hands, for Christ's sake. Hold on to my shoulders!"

It was hard for Zhilín: his feet, too, were blood-stained, and he was worn out. He kept bending down, straightening up Kostylín, and throwing him up, so that he might sit higher, and dragged him along the road.

Evidently the Tartar had heard Kostylín's shout. Zhilín heard some one riding from behind and calling in his language. Zhilín made for the brush. The Tartar pulled out his gun and fired; he screeched in his fashion, and rode back along the road.

"Well," said Zhilín, "we are lost, my friend! That dog will collect the Tartars and they will start after us. If we cannot make another three versts, we are lost." But he thought about Kostylín: "The devil has tempted me to take this log along. If I had been alone, I should have escaped long ago."

Kostylín said:

"Go yourself! Why should you perish for my sake?"

"No, I will not go,—it will not do to leave a comrade."

He took him once more on his shoulders, and held on to him. Thus they walked another verst. The woods extended everywhere, and no end was to be seen. The mist was beginning to lift, and rose in the air like little clouds, and the stars could not be seen. Zhilín was worn out.

They came to a little spring by the road; it was lined with stones. Zhilín stopped and put down Kostylín.

"Let me rest," he said, "and get a drink! We will eat our cakes. It cannot be far now."

He had just got down to drink, when he heard the tramping of horses behind them. Again they rushed to the right, into the bushes, down an incline, and lay down.

They could hear Tartar voices. The Tartars stopped at the very spot where they had left the road. They talked awhile, then they made a sound, as though sicking dogs. Something crashed through the bushes, and a strange dog made straight for them. It stopped and began to bark.

Then the Tartars came down,—they, too, were strangers. They took them, bound them, put them on their horses, and carried them off.

They traveled about three versts, when they were met by Abdul, the prisoners' master, and two more Tartars. They talked with each other, and the prisoners were put on the other horses and taken back to the village.

Abdul no longer laughed, and did not speak one word with them.

They were brought to the village at daybreak, and were placed in the street. The children ran up and beat them with stones and sticks, and screamed.

The Tartars gathered in a circle, and the old man from down-hill came, too. They talked together. Zhilín saw that they were sitting in judgment on them, discussing what to do with them. Some said that they ought to be sent farther into the mountains, but the old man said that they should be killed. Abdul disputed with them and said:

"I have paid money for them, and I will get a ransom for them."

But the old man said:

"They will not pay us anything; they will only give us trouble. It is a sin to feed Russians. Kill them, and that will be the end of it."

They all went their way. The master walked over to Zhilín and said:

"If the ransom does not come in two weeks, I will beat you to death. And if you try to run again I will kill you like a dog. Write a letter, and write it well!"

Paper was brought to them, and they wrote the letters. The stocks were put on them, and they were taken back of the mosque. There was a ditch there, about twelve feet in depth,—and into this ditch they were let down.

They now led a very hard life. The stocks were not taken off, and they were not let out into the wide world. Unbaked dough was thrown down to them, as to dogs, and water was let down to them in a pitcher. There was a stench in the ditch, and it was close and damp. Kostylín grew very ill, and swelled, and had a breaking out on his whole body; and he kept groaning all the time, or he slept. Zhilín was discouraged: he saw that the situation was desperate. He did not know how to get out of it.

He began to dig, but there was no place to throw the dirt in; the master saw it, and threatened to kill him.

One day he was squatting in the ditch, and thinking of the free world, and he felt pretty bad. Suddenly a cake fell down on his knees, and a second, and some cherries. He looked up,—it was Dina. She looked at him, laughed, and ran away. Zhilín thought: "Maybe Dina will help me."

He cleaned up a place in the ditch, scraped up some clay, and began to make dolls. He made men, horses, and dogs. He thought: "When Dina comes I will throw them to her."

But on the next day Dina did not come. Zhilín heard the tramping of horses; somebody rode by, and the Tartars gathered at the mosque; they quarreled and shouted, and talked about the Russians. And he heard the old man's voice. He could not make out exactly what it was, but he guessed that the Russians had come close to the village, and that the Tartars were afraid that they might come to the village, and they did not know what to do with the prisoners.

They talked awhile and went away. Suddenly he heard something rustle above him. He looked up; Dina was squatting down, and her knees towered above her head; she leaned over, and her necklace hung down and dangled over the ditch. Her little eyes glistened like stars. She took two cheese-cakes out of her sleeve and threw them down to him. Zhilín said to her:

"Why have you not been here for so long? I have made you some toys. Here they are!"

He began to throw one after the other to her, but she shook her head, and did not look at them.

"I do not want them," she said. She sat awhile in silence, and said; "Iván, they want to kill you!" She pointed with her hand to her neck.

"Who wants to kill me?"

"My father,—the old men tell him to. I am sorry for you."

So Zhilín said:

"If you pity me, bring me a long stick!"

She shook her head, to say that she could not. He folded his hands, and began to beg her:

"Dina, if you please! Dear Dina, bring it to me!"

"I cannot," she said. "The people are at home, and they would see me."

And she went away.

Zhilín was sitting there in the evening, and thinking what would happen. He kept looking up. The stars could be seen, and the moon was not yet up. The mullah called, and all grew quiet. Zhilín was beginning to fall asleep; he thought the girl would be afraid.

Suddenly some clay fell on his head. He looked up and saw a long pole coming down at the end of the ditch. It tumbled, and descended, and came down into the ditch. Zhilín was happy; he took hold of it and let it down,—it was a stout pole. He had seen it before on his master's roof.

He looked up: the stars were shining high in the heavens, and over the very ditch Dina's eyes glistened in the darkness. She bent her face over the edge of the ditch, and whispered: "Iván, Iván!" and waved her hands in front of her face, as much as to say: "Speak softly!"

"What is it?" asked Zhilín.

"They are all gone. There are two only at the house."

So Zhilín said:

"Kostylín, come, let us try for the last time; I will give you a lift."

Kostylín would not even listen.

"No," he said, "I shall never get away from here. Where should I go, since I have no strength to turn around?"

"If so, good-bye! Do not think ill of me!"

He kissed Kostylín.

He took hold of the pole, told Dina to hold on to it, and climbed up. Two or three times he slipped down: the stocks were in his way. Kostylín held him up, and he managed to get on. Dina pulled him by the shirt with all her might, and laughed.

Zhilín took the pole, and said:

"Take it to where you found it, for if they see it, they will beat you."

She dragged the pole away, and Zhilín went down-hill. He crawled down an incline, took a sharp stone, and tried to break the lock of the stocks. But the lock was a strong one, and he could not break it. He heard some one running down the hill, leaping lightly. He thought it was Dina. Dina ran up, took a stone, and said:

"Let me do it!"

She knelt down and tried to break it; but her arms were as thin as rods,—there was no strength in them. She threw away the stone, and began to weep. Zhilín again worked on the lock, and Dina squatted near him, and held on to his shoulder. Zhilín looked around; on the left, beyond the mountain, he saw a red glow,—the moon was rising.

"Well," he thought, "before the moon is up I must cross the ravine and get to the forest."

He got up, threw away the stone, and, though in the stocks, started to go.

"Good-bye, Dina dear! I will remember you all my life."

Dina took hold of him; she groped all over him, trying to find a place to put the cakes. He took them from her.

"Thank you," he said, "you are a clever girl. Who will make dolls for you without me?" And he patted her on the head.

Dina began to cry. She covered her eyes with her hands, and ran up-hill like a kid. In the darkness he could hear the ornaments in the braid striking against her shoulders.

Zhilín made the sign of the cross, took the lock of his fetters in his hand, that it might not clank, and started down the road, dragging his feet along, and looking at the glow, where the moon was rising. He recognized the road. By the straight road it would be about eight versts. If he only could get to the woods before the moon was entirely out! He crossed a brook,—and it was getting light beyond the mountain. He walked through the ravine; he walked and looked, but the moon was not yet to be seen. It was getting brighter, and on one side of the ravine everything could be seen more and more clearly. The shadow was creeping down the mountain, up toward him.

Zhilín walked and kept in the shade. He hurried on, but the moon was coming out faster still; the tops of the trees on the right side were now in the light. As he came up to the woods, the moon came out entirely from behind the mountains, and it grew bright and white as in the daytime. All the leaves could be seen on the trees. The mountains were calm and bright; it was as though everything were dead. All that could be heard was the rippling of a brook below.

He reached the forest,—he came across no men. Zhilín found a dark spot in the woods and sat down to rest himself.

He rested, and ate a cake. He found a stone, and began once more to break down the lock. He bruised his hands, but did not break the lock. He got up, and walked on. He marched about a verst, but his strength gave out,—his feet hurt him so. He would make ten steps and then stop. "What is to be done?" he thought. "I will drag myself along until my strength gives out entirely. If I sit down, I shall not be able to get up. I cannot reach the fortress, so, when day breaks, I will lie down in the forest for the day, and at night I will move on."

He walked the whole night. He came across two Tartars only, but he heard them from afar, and so hid behind a tree.

The moon was beginning to pale, and Zhilín had not yet reached the edge of the forest.

"Well," he thought, "I will take another thirty steps, after which I will turn into the forest, where I will sit down."

He took the thirty steps, and there he saw that the forest came to an end. He went to the edge of it, and there it was quite light. Before him lay the steppe and the fortress, as in the palm of the hand, and to the left, close by at the foot of the mountain, fires were burning and going out, and the smoke was spreading, and men were near the camp-fires.

He took a sharp look at them: the guns were glistening,—those were Cossacks and soldiers.

Zhilín was happy. He collected his last strength and walked down-hill. And he thought: "God forfend that a Tartar rider should see me in the open! Though it is not far off, I should not get away."

No sooner had he thought so, when, behold, on a mound stood three Tartars, not more than 150 fathoms away. They saw him, and darted toward him. His heart just sank in him. He waved his arms and shouted as loud as he could:

"Brothers! Help, brothers!"

Our men heard him, and away flew the mounted Cossacks. They started toward him, to cut off the Tartars.

The Cossacks had far to go, but the Tartars were near. And Zhilín collected his last strength, took the stocks in his hand, and ran toward the Cossacks. He was beside himself, and he made the sign of the cross, and shouted:

"Brothers! Brothers! Brothers!"

There were about fifteen Cossacks.

The Tartars were frightened, and they stopped before they reached him. And Zhilín ran up to the Cossacks.

The Cossacks surrounded him, and asked:

"Who are you? Where do you come from?"

But Zhilín was beside himself, and he wept, and muttered:

"Brothers! Brothers!"

The soldiers ran out, and surrounded Zhilín: one gave him bread, another gruel, a third vódka; one covered him with a cloak, another broke off the lock.

The officers heard of it, and took him to the fortress. The soldiers were happy, and his companions came to see him.

Zhilín told them what had happened, and said:

"So I have been home, and got married! No, evidently that is not my fate."

And he remained in the service in the Caucasus. Not till a month later was Kostylín ransomed for five thousand. He was brought back more dead than alive.