Figure 1: US profit rates accounting for (–) and abstracting from (-) the impact of financial relations [23]

From International Socialism (2nd series), No.115, Summer 2007.

Copyright © International Socialism.

Downloaded with thanks from the International Socialism Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Marxists’ Internet Archive.

The “tendency of the rate of profit to fall” is one of the most contentious elements in Karl Marx’s intellectual legacy. [1] He regarded it as one of his most important contributions to the analysis of the capitalist system, calling it, in his first notebooks for Capital (now published as the Grundrisse), “in every respect the most important law of modern political economy”. [2] But it has been subjected to criticism ever since his argument first appeared in print with the publication of volume three of Capital in 1894.

The first criticisms in the 1890s came from opponents of Marxism, such as the liberal Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce and the German neoclassical economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. But they have been accepted since by many Marxists – from Paul Sweezy in the 1940s to people such as Gérard Duménil and Robert Brenner today.

The argument was and is important. For Marx’s theory leads to the conclusion that the there is a fundamental, unreformable flaw in capitalism. The rate of profit is the key to capitalists being able to achieve their goal of accumulation. But the more accumulation takes place, the more difficult it is for them make sufficient profit to sustain it: “The rate of self-expansion of capitalism, or the rate of profit, being the goad of capitalist production, its fall ... appears as a threat to the capitalist production process”. [3]

This “testifies to the merely historical, transitory character of the capitalist mode of production” and to the way that “at a certain stage it conflicts with its own further development”. [4] It showed that “the real barrier of capitalist production was capital itself”. [5]

Marx’s basic line of argument was simple enough. Each individual capitalist can increase his (or occasionally her) own competitiveness through increasing the productivity of his workers. The way to do this is by using a greater quantity of the “means of production” – tools, machinery and so on – for each worker. There is a growth in the ratio of the physical extent of the means of production to the amount of labour power employed, a ratio that Marx called the “technical composition of capital”.

But a growth in the physical extent of the means of production will also be a growth in the investment needed to buy them. So this too will grow faster than the investment in the workforce. To use Marx’s terminology, “constant capital” grows faster than “variable capital”. The growth of this ratio, which he calls the “organic composition of capital” [6], is a logical corollary of capital accumulation.

Yet the only source of value for the system as a whole is labour. If investment grows more rapidly than the labour force, it must also grow more rapidly than the value created by the workers, which is where profit comes from. In short, capital investment grows more rapidly than the source of profit. As a consequence, there will be a downward pressure on the ratio of profit to investment – the rate of profit.

Each capitalist has to push for greater productivity in order to stay ahead of competitors. But what seems beneficial to the individual capitalist is disastrous for the capitalist class as a whole. Each time productivity rises there is a fall in the average amount of labour in the economy as a whole needed to produce a commodity (what Marx called “socially necessary labour”), and it is this which determines what other people will eventually be prepared to pay for that commodity. So today we can see a continual fall in the price of goods such as computers or DVD players produced in industries where new technologies are causing productivity to rise fastest.

Three arguments have been raised time and again against Marx.

The first is that there need not be any reason for new investment to take a “capital intensive” rather than a “labour intensive” form. If there is unused labour available in the system, there seems no reason why capitalists should invest in machines rather than labour. There is a theoretical reply to this argument. Capitalists are driven to seek innovations in technologies that keep them ahead of their rivals. Some such innovations may be available using techniques that are not capital intensive. But there will be others that require more means of production – and the successful capitalist will be the one whose investments provide access to both sorts of innovation.

There is also an empirical reply. Investment in material terms has in fact grown faster than the workforce. So, for instance, the net stock of capital per person employed in the US grew at 2 to 3 percent a year from 1948 to 1973. [7] In China today much of the investment is “capital intensive”, with the employed workforce only growing at about 1 percent a year, despite the vast pools of rural labour.

The second objection to Marx’s argument is that increased productivity reduces the cost of providing workers with their existing living standards (“the value of their labour power”). The capitalists can therefore maintain their rate of profit by taking a bigger share of the value created.

This objection is easy to deal with. Marx himself recognised that rises in productivity that reduce the proportion of the working day needed for workers to cover the cost of their own living standards could form a “countervailing influence” to his law. The capitalists could then grab a greater share of their workers’ labour as profits (an increased “rate of exploitation”) without necessarily cutting real wages. But there was a limit to how far this counter-influence could operate. If workers’ laboured for four hours a day to cover the costs of keeping themselves alive, that could be cut by an hour to three hours a day. But it could not be cut by five hours to minus one hour a day. By contrast, there was no limit to the transformation of workers’ past labour into ever greater accumulations of the means of production. Increased exploitation, by increasing the profit flowing to capital, increased the potential for future accumulation. Another way to put the argument is to see what happens with a hypothetical “maximum rate of exploitation”, when the workers labour for nothing. It can be shown that eventually even this is not enough to stop a fall in the ratio of profit to investment.

The final objection is “Okishio’s theorem”. Changes in technique alone, it is claimed, cannot produce a fall in the rate of profit, since capitalists will only introduce a new technique if it raises their profits. But a rise in the profit rate of one capitalist must raise the average profit of the whole capitalist class. Or as Ian Steedman put it, “The forces of competition will lead to that selection of production methods industry by industry which generates the highest possible uniform rate of profit through the economy”. [8] The conclusion drawn from this is that the only things that can reduce profit rates are increased real wages or intensified international competition.

Missing out from many presentations of this argument is the recognition that the first capitalist to adopt a technique gets a competitive advantage over his fellow capitalists, which enables him to gain extra profits, but that this extra profit disappears once the technique is generalised.What the capitalist gets in money terms when he sells his goods depends upon the average amount of socially necessary labour contained in them. If he introduces a new, more productive, technique, but no other capitalists do, he is producing goods worth the same amount of socially necessary labour as before, but with less expenditure on real, concrete labour power. His profits rise. [9] But once all capitalists producing these goods have introduced these techniques, the value of the goods falls until it corresponds to the average amount of labour needed to produce them using the new techniques. [10]

Okishio and his followers use the counter-argument that any rise in productivity as a result of using more means of production will cause a fall in the price of its output, so reducing prices throughout the economy – and thereby the cost of paying for the means of production. This cheapening of investment will, they claim, raise the rate of profit.

At first glance the argument looks convincing – and the simultaneous equations used in the mathematical presentation of the theorem have convinced many Marxist economists. It is, however, false. It rests upon a sequence of logical steps which you cannot take in the real world. Investment in a process of production takes place at one point in time. The cheapening of further investment as a result of improved production techniques occurs at a later point in time. The two things are not simultaneous. [11] It is a silly mistake to apply simultaneous equations to processes taking place through time.

There is an old saying: “You cannot build the house of today with the bricks of tomorrow.” The fact that the increase in productivity will reduce the cost of getting a machine in a year’s time does not reduce the amount the capitalist has to spend on getting it today.

Capitalist investment involves using the same fixed constant capital (machinery and buildings) for several cycles of production. The fact that undertaking investment would cost less after the second, third or fourth round of production does not alter the cost of undertaking it before the first round. The decline in the value of their already invested capital certainly does not make life any easier for the capitalists. To survive in business they have to recoup, with a profit, the full cost of their past investments, and if technological advance meant these investments are now worth, say, half as much as they were previously, they have to pay out of their gross profits to write off that sum. What they have gained on the swings they have lost on the roundabouts, with “depreciation” of capital due to obsolescence causing them as big a headache as a straightforward fall in the rate of profit.

The implications of Marx’s argument are far reaching. The very success of capitalism at accumulating leads to problems for further accumulation. Crisis is the inevitable outcome, as capitalists in key sections of the economy no longer have a rate of profit sufficient to cover their investments. And the greater the scale of past accumulation, the deeper the crises will be.

The crisis, however, is not the end of the system. Paradoxically it can open up new prospects for it. By driving some capitalists out of business it can permit a recovery of the profits of others. Means of production can be bought at bargain basement prices, raw material prices slump and unemployment forces workers to accept low wages. Production once again becomes profitable and accumulation can restart. There has long been a dispute among economists who accept Marx’s law about the implications of this. Some have argued that the rate of profit will tend to decline in the long term, decade after decade. Not only will there be ups and downs with each boom-slump cycle, there will also be a long term downward trend, making each boom shorter than the one before and each slump deeper. Others Marxists, by contrast, have argued that restructuring can restore the rate of profit to its earlier level until rising investment lowers it again. According to this view, there is a cyclical motion of the rate of profit, punctuated by intense crises of restructuring, not an inevitable long term decline. So Marx’s law should be called “the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall and its countervailing tendencies”. [12]

There have been periods in the history of the system in which crises got rid of unprofitable capital on a sufficient scale to stop a long term decline in profit rates. There was, for instance, a decline in profit rates in the early stages of the industrial revolution, from very high rates for the pioneers in the cotton industry in the 1770s and 1780s to much lower rates by the first decade of the 19th century. [13] This led Adam Smith and David Ricardo to see falling profit rates as inevitable (with Smith blaming them on competition and Ricardo on the diminishing returns of physical output in agriculture). But profit rates then seem to have recovered substantially. Robert C. Allen claims they were twice as high in 1840 as in 1800. [14] His figures (if accurate) are compatible with the “restructuring restoring the rate of profit” argument, since there were three economic crises between 1810 and 1840, with 3,300 firms going bust in 1826 alone. [15]

If crises can always counteract the fall in the rate of profit in this way Marx was wrong to see his law as spelling the death knell of capitalism, since the system has survived recurrent crises over the past 180 years.

But those who rely on this argument assume restructuring can always take place in such a way as to harm some capitals but not others. Michael Kidron presented a very important challenge to this contention in the 1970s. It was based on understanding that the development of capitalism is not simply cyclical, but also involves transformation through time – it ages. [16]

The process by which some capitals grow at the expense of others – what Marx calls the “concentration and centralisation” of capital – eventually leads to a few very large capitals playing a predominant role in particular parts of the system. Their operation becomes intertwined with those of the other capitals, big and small, around them. If the very large capitals go bust, it disrupts the operation of the others – destroying their markets, and cutting off their sources of raw materials and components. This can drag previously profitable firms into bankruptcy alongside the unprofitable in a cumulative collapse that risks creating economic “black holes” in the heart of the system.

This began to happen in the great crisis of the interwar years. Far from bankruptcies of some firms bringing the crisis to end after a couple of years they deepened its impact. As a consequence, capitals everywhere turned to states to protect them. Despite their political differences, this was what was common to the New Deal in the US, the Nazi period in Germany, the emerging populist regimes in Latin America or the final acceptance of Keynesian state intervention as the economic orthodoxy in wartime Britain. Such interdependence of states and big capitals was the norm right across the system in the first three decades following the Second World War, an arrangement that has variously been called “state capitalism” (my preferred term), “organised capitalism” or “Fordism”. [17]

The intervention of the state always had doubled edged repercussions. It prevented the first symptoms of crisis developing into out-and-out collapse. But it also obstructed the capacity of some capitals to restore their profit rates at the expense of others.

This was not a great problem in the first decades after 1945, since the combined impact of the interwar slump and the Second World War had already caused a massive destruction of old capital (according to some estimates a third of the total). Accumulation was able to restart with higher profit rates than in the pre-war period, and rates hardly declined, or did so slowly. [18] Capitalism could enjoy what is often now called its “golden age”. [19]

But when profit rates did begin to fall from the 1960s onwards the system found itself caught between the danger of “black holes” and of failing to restructure sufficiently to restore those rates. The system could not afford to risk restructuring by letting crises rip through it. States intervened to ward off the threat of big bankruptcies. But in doing so they prevented the system restructuring sufficiently to overcome the pressures that had caused the threat of bankruptcy. The system, as Kidron put it in an editorial for this journal, was “sclerotic”. [20]

As I wrote in this journal in 1982:

State intervention to mitigate the crisis can only prolong it indefinitely. This does not mean the world economy is doomed simply to decline. An overall tendency to stagnation can still be accompanied by boomlets, with small but temporary increases in employment. Each boomlet, however, only aggravates the problems of the system as a whole and results in further general stagnation, and extreme devastation for particular parts of the system.

I argued that “two or three advanced countries” going bankrupt might “provide the system with the “opportunity for a new round of accumulation”, but that those running the other parts of the system would do their best to avoid such bankruptcy, lest it pulled down other economies and the banks, leading to “the progressive collapse of other capitals”. My conclusion was that “the present phase of crisis is likely to go on and on – until it is resolved either by plunging much of the world into barbarism or by a succession of workers’ revolutions”. [21]

How does the empirical record of profit rates over the past 30 years measure up to these various arguments? And what are the implications for today?

There have been a number of attempts to calculate long term trends in profit rates. The results are not always fully compatible with each other, since there are different ways of measuring investment in fixed capital, and the information on profits provided by companies and governments are subject to enormous distortions (companies will often do their best to understate the profits to governments, for tax reasons, and to workers, in order to justify low wages; they also often overstate their profits to shareholders, in order to boost their stock exchange ratings and their capacity to borrow). Nevertheless, Fred Moseley, Thomas Michl, Anwar Shaikh and Ertugrul Ahmet Tonak, Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy, Ufuk Tutan and Al Campbell, Robert Brenner, Edwin N. Wolff, and Piruz Alemi and Duncan K. Foley [22] have all followed in the footsteps of Joseph Gillman and Shane Mage who carried through empirical studies of profit rate trends in the 1960s.

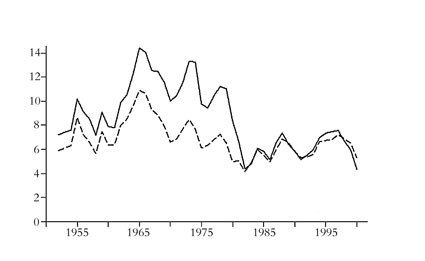

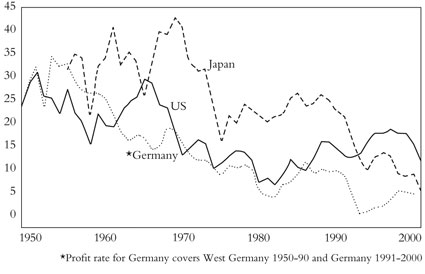

A certain pattern emerges, which is shown in graphs given by Duménil and Lévy (figure 1) for the whole business sector in the US and by Brenner (figure 2) for manufacturing in the US, Germany and Japan.

|

Figure 1: US profit rates accounting for (–) and abstracting from (-) the impact of financial relations [23] |

|

There is general agreement that profit rates fell from the late 1960s until the early 1980s. There is also agreement that profit rates partially recovered after the early 1980s, but with interruptions at the end of the 1980s and the end of the 1990s. There is also an important area of agreement that the fall from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s was not a result of rising wages, since this was the period in which US real wages began a decline which was not partially reversed until the late 1990s. Michl [24], Moseley, Shaikh and Tonak, and Wolff [25] all conclude that the rising ratio of capital to labour was an element in reducing profit rates. This conclusion is an empirical refutation of the Okishio position. “Capital intensive” investments by capitalists aimed at raising their individual competitiveness and profitability have had the effect of causing profitability throughout the economy to fall. Marx’s basic theory is validated.

|

Figure 2: US, German and Japanese manufacturing net profits rates [26] |

|

Profit rates did recover from about 1982 onwards – but they only made up about half the decline that had taken place in the previous period. According to Wolff, the rate of profit fell by 5.4 percent from 1966-79 and then “rebounded” by 3.6 percent from 1979-97; Fred Moseley calculates that it “recovered ... only about 40 percent of the earlier decline”; [27] Duménil and Lévy that “the profit rate in 1997” was “still only half of its value of 1948, and between 60 and 75 percent of its average value for the decade 1956-65”. [28]

Why did profit rates recover? One important factor was an increase in the rate of exploitation throughout the economy, as shown by the rising share going to “capital” and opposed to “labour” in national output: Moseley showed a rise in the “rate of surplus value from 1.71 in 1975 to 2.22 in 1987”. [29]

There was, however, also a slowdown in the growth of the ratio of investment to workers (the “organic composition of capital”), at least until the mid-1990s. An important change took place in the system from around 1980 onwards – crises begin to involve large scale bankruptcies for the first time since the interwar years:

During the period from World War II through the 1970s, bankruptcy was not a major topic in the news. With the exception of railroads, there were not many notable business failures in the US. During the 1970s, there were only two corporate bankruptcies of prominence, Penn Central Transportation Corporation in 1970 and W.T. Grant Company in 1975.

But:

During the 1980s and early 1990s record numbers of bankruptcies, of all types, were filed. Many well known companies filed for bankruptcy ... Included were LTV, Eastern Airlines, Texaco, Continental Airlines, Allied Stores, Federated Department Stores, Greyhound, R.H. Macy and Pan Am ... Maxwell Communication and Olympia & York. [30]

The same story was repeated on a bigger scale during the crisis of 2001-2. For instance, the collapse of Enron was, as Joseph Stiglitz writes, “the biggest corporate bankruptcy ever – until WorldCom came along”. [31]

This was not just a US phenomenon. It was a characteristic of Britain in the early 1990s as bankruptcies like those of the Maxwell Empire and Olympia & York showed, and, although Britain avoided a full recession in 2001-2, two once dominant companies, Marconi/GEC and Rover, went down, as well as scores of recently established dotcom and hi-tech companies. The same phenomenon was beginning to be visible in continental Europe, with an added twist in Germany that most of the big enterprises of the former East Germany went bust or were sold off at bargain basement prices to West German firms [32], and then in Asia with the crisis of 1997-8. On top of this there was the bankruptcy of whole states – notably the USSR, with a GDP that was at one stage a third or even half that of the US. Most of the left held a confused belief that these were “socialist” states. This prevented many commentators from understanding that these states collapsed because the rate of profit was no longer high enough to cover their cost of equipping themselves for international competition. [33] It also prevented them from analysing the impact that writing off these vast amounts of capital had on the world system. [34]

What occurred through these decades was a process of recurrent “restructuring through crisis” on an international scale. However, it was only a limited return of the old mechanism for clearing out unprofitable capitals to the benefit of the survivors. There were still many cases in which the state intervened to prop up very big firms or to pressurise the banking system to do so. This happened in the US with the near bankruptcy of Chrysler in 1979-80 [35], with the crisis of the S&Ls (effectively US building societies) in the late 1980s and the collapse of the giant derivatives gambler Long Term Capital Management in 1998. On each occasion fear of economic, social and political instability prevented the crisis clearing unprofitable capitals from the system. Orlando Capita Leiva tells how in the United States “the state supported ... restructuring. In 1970 public investment was only 10 percent of private investment. It increased to 24 percent in 1990 and from then on maintained levels almost double those of 1970”. [36]

Official use of the rhetoric of neoliberalism does not preclude a continuing strong element of state capitalism in actual government policy. This is true not just of the US. Governments as varied as those of the Scandinavian countries and Japan have rushed to prop up banks whose collapse might damage the rest of the national financial system – even if, as a last resort, this involves nationalisation. [37] The government of Germany poured billions into the eastern part of the recently unified country after companies found their newly acquired subsidiaries could not be profitable otherwise. And the world financial institutions have reacted to successive debt crises with schemes that protect big Western banks from going under, despite occasional complaints from, for instance, the Economist to the effect that this prevents the system from taking the only medicine that will restore its full vigour.

Moseley, Shaikh and Tonak, and Simon Mohun have all noted another feature of capitalism’s most recent development – one highlighted by Kidron back in the 1970s. This is the growing “non-productive” portion of the economy.

Mainstream neoclassical economics regards all economic activities involving buying and selling as “productive”. This follows from its limited focus on the way transactions take place in markets. Marx, like Adam Smith and David Ricardo before him, had a deeper concern – to discover the dynamics of capitalist growth. He therefore further developed a distinction to be found in Smith between “productive” and “unproductive” labour. For Marx, productive labour was that which created surplus value through expanding production. Unproductive labour was that which, rather than expanding production, was simply distributing, protecting or wasting what was already produced – for instance, the labour of personal servants, policemen, soldiers or sales personnel.

Marx’s distinction was not between material production and “services”. Some things categorised as “services” add to the real wealth of the world. Moving things from where they are made to where they can be consumed, as is done by some transport workers, is therefore productive. Acting in a film is likewise productive insofar as it yields a profit for a capitalist by giving people enjoyment as so improving their living standard. By contrast, acting in an advert whose only function is to sell something already produced is not productive.

Marx’s categorisation has to be refined to come to terms with present day capitalism, in which things like education and heath services are much more important than when he was writing. Most present day Marxists would accept that those elements of teaching that increase the capacity of people to produce things (as opposed to merely disciplining children) are at least indirectly productive. Kidron went further and argued that what was productive was that which served the further accumulation of capital. The production of means of production did this, and so did the production of goods that kept workers and their families fit and healthy enough to be exploitable (i.e. good that replenished their “labour power”). But production that merely provided luxuries for the capitalist class and their hangers-on should not be regarded as productive, nor should that which went into arms. [38]

Unproductive labour is of central importance to present day capitalism, regardless of the exact definition given to it. Fred Moseley estimates the numbers in commerce in the US grew from 8.9 million to 21 million between 1950 and 1980, and the number in finance from 1.9 million to 5.2 million, while the productive workforce only grew from 28 million to 40.3 million. [39] Shaikh and Tonak calculate that the share of productive out of total labour in the US fell from 57 percent to 36 percent between 1948 and 1989. [40] Simon Mohun has calculated that the share of “unproductive” wages and salaries in “material value added” in the US grew from 35 percent in 1964 to over 50 percent in 2000. [41] Kidron calculated that, using his wide definition, “Three fifths of the work actually undertaken in the US in 1970s was wasted from capital’s own point of view”. [42]

Moseley, Shaikh and Tonak, and Kidron in his later writings [43] had no doubt. The burden of providing for unproductive labour serves as a drain on surplus value and the rate of profit. [44] Moseley, and Shaikh and Tonak, calculated the rate of profit in “productive” sectors (the “Marxian rate of profit”), and then compared their results with those provided for the economy as a whole by corporations and the US government’s National Institute of Pension Administrators (NIPA). [45] Shaikh and Tonak calculate that from 1948-89 “the Marxian rate of profit falls by almost a third ... The NIPA based average rates even faster, by over 48 percent, and the corporate the fastest of all by over 57 percent. These more rapid declines can be explained by the relative rise in the proportion of unproductive to productive activities”. [46] Moseley concludes that “in the post-war US economy through the late 1970s the conventional rate of profit declined even more than the Marxian rate” – by 40 percent as opposed to 15-20 percent. He has argued that the in the 1990s it was mainly the rise in the level of unproductive labour that stopped the rate of profit fully recovering.

Why have unproductive expenditures grown like this, even to the extent of choking off what might otherwise be healthier profit rates? Different factors are involved, but each is itself a reaction to low profit rates (and attempts by firms and governments to keep crisis at bay):

There is a vicious circle. Reactions by individual firms and states to the falling rate of profit have the effect of further reducing the resources available for productive accumulation. [47]

But the effect of unproductive expenditures is not only to lower the rate of profit. It can also reduce upward pressure on the organic composition of capital. This was an insight used by Michael Kidron to explain the “positive” impact of massive arms spending on the system in the post-war decades. He saw it, like luxury consumption by the ruling class and its hangers-on, as having a beneficial side-effect for those running the system – at least for a time.

Labour which is “wasted”, he argued, cannot add to the pressure for accumulation to be ever more capital intensive. Value which would otherwise go into raising the ratio of means of production to workers is siphoned out of the system. Accumulation is slower, but it continues at a steady pace, like the tortoise racing the hare in Aesop’s fable. Profit rates are weighed down by the waste, but do not face a sudden thrust into the depths from a rapid acceleration of the capital-labour ratio.

This account seems to fit the early post-war period. Arms spending at around 13 percent of US national output (and with indirect expenditures, perhaps 15 percent) was a major diversion of surplus value away from further accumulation. It was also an expenditure that the US ruling class expected to gain from, in that it helped their global hegemony (both in confronting the USSR and binding the European capitalist classes to the US) and guaranteed a market to some important productive sectors of the US economy. In this sense, the capitalists could regard arms, like their own luxury consumption, as something to their advantage – very different in this sense to “unproductive” expenditures on improving the conditions of the poor. And if it reduced the rate of accumulation, this was not catastrophic since the restructuring of capital through slump and war had already boosted accumulation to higher trajectory than that known in the 1930s. Domestically, all firms suffered the same handicap, and so none lost out to others in competition for markets. And internationally, in the early post-war years, other countries involved in significant economic competition with the US (such as the old imperial powers of Britain and France) were handicapped by relatively high arms spending of their own.

Today things are very different. Since the early 1960s the re-emergence of major foreign economic competitors has created a powerful pressure for the US to reduce the share of national output going towards arms. Boosting arms spending in the mid-1960s during the Vietnam War and in the 1980s during the “second Cold War” gave only a short term fillip to the US economy before revealing immense problems. George Bush’s rise in arms spending from 3.9 percent 4.7 percent of GNP (equal to about a third of net business investment) has exacerbated the US’s burgeoning budget and foreign trade deficits.

The effect of all of these forms of “waste” is much less beneficial to the system as a whole than half a century ago. They may still reduce the downward pressures on the rate of profit from the organic composition of capital – it certainly does not rise as rapidly as it would if all surplus value went into accumulation. But the price the advanced capitalist countries pay for this is slow productive accumulation and slow long term rates of growth. Hence the repeated “neoliberal” attempts by capitals and states to raise profit rates by cutting back on what they pay employed workers, the old, the unemployed and the long term sick; the resort to market mechanism to try to reduce costs in education and health; the insistence that Third World countries pay their pound of flesh on their loans; and the US adventure of trying to seize control of the second biggest source of the world’s most important raw material.

It is wrong to describe the situation as one of permanent crisis [48] – rather it is one of recurrent economic crises. The economic recoveries of the 1980s (especially in Japan) and 1990s (in the US) were more than “boomlets”. Low levels of past profitability do not stop capitalists imagining that there are miraculous profits to be made in future and sucking in surplus value from all over the world to be ploughed into projects aimed at obtaining them. Many of these are purely speculative gambles in unproductive spheres, as with bubbles in real estate, commodity markets, share prices and so on. But capitalists can also fantasise about profits to be made by pouring resources into potentially productive sectors, and so create rapid booms lasting several years. Investment in the US doubled between 1991 and 1999. [49] When the bubble burst it was discovered that an immense investment in real things such as fibre optic telecommunication networks had been undertaken that would never be profitable, with the Financial Times writing of a “$1000 billion bonfire of wealth”. [50]

That was a period in which there was some real recovery of the rate of profit. But that did not do away with the “irrational exuberance” of expecting speculative profits where they did not exist. Virtually every major company deliberately inflated its profits so as to take make speculative gains, with proclaimed profits around 50 percent higher than real profits. [51]

There are many signs that in the US (and probably Britain) we may be approaching a similar phase now. Investment in the US, after declining in the last recession, is now back to the levels of the late 1990s. [52] But the US recovery has been based upon massive government deficits, on balance of payments deficits covered by inflows of lending from abroad, and on consumers borrowing to cover their living costs as the share of “employee incomes in US GDP has fallen form 49 percent to 46 percent”. [53] This is the background to the upsurge of speculative ventures such as hedge funds, derivatives markets, the housing bubble and, now, massive borrowing for private equity takeovers of very big corporations (very reminiscent of the “barbarians at the gate” issue of junk bonds in the giant takeovers of the late 1980s). Against such a background, corporate profits will be being puffed up until they lose touch with reality, and things will seem to be going very well until overnight it is discovered they are going badly. And, as they say, when the US gets a cold, the UK can easily catch influenza.

For the moment profit rates in Britain appear to be high. According to one calculation they reached 15.5 percent for all non-financial private corporations in the fourth quarter of 2006 – the highest figure since 1969. Under New Labour the share of profits in GDP has reached a record of nearly 27 percent. [54] But the figures for average profits rates will have been boosted by the current high levels of profit on North Sea oil and gas. And calculations of profits made by British firms are not the same as profits made in Britain, given the very high dependence of big firms on their overseas activities (more so than in any other large advanced capitalist country). “Service sector” profitability is high. However, profitability in the much diminished but still important industrial sector has fallen from about 15 percent in 1998 to about 10 percent now. As in the US there are currently many enthusiasts for capitalism who fear the good times are about to end as they eventually did in the 1970s, the 1980s and the 1990s.

There are even doubts about the one part of the world system where immense productive investments are taking place – China. Some commentators see this country as the salvation of the system as a whole. Chinese capital has been able plough much more surplus value back into investment – more than 40 percent of national output – than in the US, Europe or even Japan. It has been able to exploit its workers more, and it has not so far been held back by the levels of unproductive expenditure that characterise advanced capitalist countries (although the present real estate boom is characterised by a proliferation of office sky scrapers, hotels and shopping malls). All this has enabled it to emerge as a major competitor with the advanced capitalist countries in export markets for many products. But its very high levels of investment are already having an impact on profitability. One recent attempt to apply Marxist categories to the Chinese economy calculates that its profit rates as fell from 40 percent in 1984 to 32 percent in 2002, while the organic composition of capital has increased by 50 percent. [55] There are some Western observers who are convinced that the profitability of some big Chinese corporations is very low, but that this is concealed by the pressure on the big state-run banks to keep them expanding. [56]

Speculation about what will happen next is easy, but pointless. The general contours of the system are decipherable, but the myriad individual factors that determine how these translate into reality in the course of a few months or even years are not. What matters is to recognise that the system has only been able to survive – and even, spasmodically, grow quite fast for the past three decades – because of its recurrent crises, the increased pressure on workers’ conditions and the vast amounts of potentially investable value that are diverted into waste. It has not been able to return to the “golden age” and it will not be able to do so in future. It may not be in permanent crisis, but it is in a phase of repeated crises from which it cannot escape, and these will necessarily be political and social as well as economic.

1. This article is based on research for a forthcoming book on capitalism in the 21st century. I would appreciate suggestions and constructive criticism. Please email [email protected]

2. Marx, 1973, p.748.

3. Marx, 1962, pp.236-237.

4. Marx, 1962, p.237.

5. Marx, 1962, p.245.

6. The organic composition of capital was depicted algebraically by Marx by the formula c/v, where c = constant capital, and v = variable capital.

7. Clarke, 1979, p.427. See also the comment by M.N. Bailey, p.433-436. For a graph showing the long term rise of the capital-labour ration, see Duménil and Lévy, 1993, p.274.

8. Steedman, 1985, p.64; compare also pp.128-129.

9. For Marx’s argument with a numerical example, see Marx, 1965, pp.316-317.

10. For more on this argument, with a simple numerical example of my own, see Harman, 1984, pp.29-30.

11. This point was made by Robin Murray in a reply to an attempt by Andrew Glyn to use a “corn model” to disprove the falling rate of profit (Muray, 1973), and was taken up by Ben Fine and Lawrence Harris in Rereading Capital (Fine and Harris, 1979). It now stands are the centre of the arguments put forward by the “temporal single-system interpretation” of Alan Freeman and Andrew Kliman. See, for instance Freeman and Carchedi, 1996, and Kliman, 2007.

12. Fine and Harris, 1979, p.64. The argument is also accepted by Andrew Kliman, see Kliman, 2007, pp.30-31.

13. See the figures in Harley, 2001.

14. Allen, 2005.

15. Flamant and Singer-Kérel, 1970, p.18.

16. Hence Kidron’s description of present day capitalism as “ageing capitalism”, rather than the term “late capitalism” popularised by Ernest Mandel.

17. The latter term is misleading, since it equates mass production methods of exploitation, rising consumer spending and state intervention in industry, as if someone set out to produce all three; rather than the logic of the concentration and centralisation of capital working itself out. The term “post-Fordism” is even more confusing, since mass production methods remain in many sectors of the economy, and there is everywhere a complex interaction between states and capitals.

18. Different measures of profit rates give slightly different pictures in these decades.

19. Mike Kidron ascribed this to the role of arms spending in his two books, Kidron, 1970a, and Kidron, 1974, a view which I endorsed in Harman, 1984. More on this question later in this article.

20. Kidron, 1970b, p.1.

21. Harman, 1982, p.83. This article was reprinted, with minor changes, as chapter three of Harman, 1984.

22. Alemi and Foley, 1997.

23. Duménil and Lévy, 2005a, p.11.

24. Michl, 1988.

25. Wolff, 2003, pp.479-499.

26. Brenner, 2006, p.7.

27. Moseley, 1997.

28. Duménil and Lévy, 2005b.

29. Moseley, 1991, p.96.

30. Mastroianni, 2006, chapter 11.

31. Stiglitz, 2004.

32. Dale, 2004, p.327.

33. See Harman, 1977, and Harman, 1990.

34. It took repeated comments by Ken Muller to make me even begin to try to think this through.

35. “In a rare emotional appeal to the House of Representatives, Speaker Tip O’Neill brought a hush to the chamber as he recalled the dark days of the Great Depression and warned that failure to save Chrysler would result in worker layoffs large enough to trigger a new depression. Said he: ‘We won’t be able to dig ourselves out for the next ten years’.” Time magazine, 31 December 1989.

36. Leiva, 2007, p.12.

37. See OECD, 1996.

38. See the chapter Waste US: 1970 in Kidron, 1974. See also my discussion of this in Harman, 1984.

39. Moseley, 1991, p.126. He mistakenly underestimates the amount of productive and unproductive labour by excluding the public sector from the capitalist economy, see p.35.

40. Sheikh and Tonak, 1994, p.110.

41. Mohun, 2006, figure 6.

42. Kidron, 1974, p.56.

43. Kidron, 2002, p.87.

44. However, Duménil and Lévy do not accept that unproductive expenditures necessarily lower the rate of profit. They contend that unproductive expenditures can help the rate of profit through the impact of increased managerial supervision on productivity. They claim this explains the rise in the rate of profit which occurred between the 1920s and the late 1940s. Their argument is doubly wrong. The most obvious cause of that rise was the destruction of capital in slump and war. And increased productivity in itself cannot increase the rate of profit, since its effect, once it takes place right across the system, is to lower the socially necessary labour required to produce, and hence the value of, each unit of output. Their position follows from their inversion of Marx’s relationship between productivity and value, which in effect abandons the labour theory of value by denying it is possible to use values as a basis for prices. See my review of their Capital Resurgent, Harman, 2005.

45. Moseley, 1991, p.104.

46. Shaikh and Tonak, 1994, p.124.

47. One fault with Moseley’s analysis is that he does not see this, but looks for other factors to explain the rising level of waste.

48. It was a mistake on my part to use such a formulation in 1982 – although I think excusable as we faced only the second real recession my generation had experienced and did so a mere four years after the end of the first.

49. Leiva, 2007, p.11.

50. Financial Times, 5 September 2001.

51. The Economist, 23 June 2001.

52. Leiva, 2007, p.11.

53. Riley, 2007.

54. All figures on British profit rates are from Barell and Kirkby, 2007.

55. O’Hara, 2006.

56. For much more on this, see Harman, 2006.

Alemi, Piruz and Duncan K. Foley, 1997, The Circuit of Capital, US Manufacturing and Non-financial Corporate Business Sectors, 1947-1993, manuscript, September 1997.

Allen, Robert C., 2005, Capital Accumulation, Technological Change, and the Distribution of Income during the British Industrial Revolution, Department of Economics, Oxford University.

Barell, Ray and Simon Kirkby, 2007, Prospects for the UK economy, National Institute Economic Review, April 2007.

Brenner, Robert, 2006, The Economics of Global Turbulence (Verso).

Clarke, Peter, 1979, Issues in the Analysis of Capital Formation and Productivity Growth, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, volume 1979, number 2.

Dale, Gareth, 2004, Between State Capitalism and Globalisation (Peter Lang).

Duménil, Gérard, and Dominique Lévy, 1993, The Economics of the Profit Rate (Edward Elgar).

Duménil, Gérard and Dominique Lévy, 2005a, The Real and Financial Components of Profitability.

Duménil, Gérard and Dominique Lévy, 2005b, The Profit Rate: Where and How Much Did it Fall? Did It Recover? (USA 1948-1997).

Fine, Ben, and Laurence Harris, 1979, Rereading Capital (Macmillan).

Flamant, Maurice, and Jeanne Singer-Kérel, 1970, Modern Economic Crises (Barrie and Jenkins).

Freeman, Alan, and Guglielmo Carchedi (eds.), 1996, Marx and Non-equilibrium Economics

(Edgar Elgar).

Harley, C Knick, 2001, Cotton Textiles and the Industrial Revolution Competing Models and Evidence of Prices and Profits, Department of Economic, University of Western Ontario, May 2001.

Harman, Chris, 1977, Poland: Crisis of State Capitalism, International Socialism 93 and 94, first series (November/December 1976, January 1977)

Harman, Chris, 1982, Arms, State Capitalism and the General Form of the Current Crisis, International Socialism 26 (spring 1982).

Harman, Chris, 1984, Explaining the Crisis: A Marxist Reappraisal (Bookmarks).

Harman, Chris, 1990, The Storm Breaks, International Socialism 46 (spring 1990).

Harman, Chris, 2005, Half-explaining the Crisis, International Socialism 108 (Autumn 2005).

Harman, Chris, 2006, China’s economy and Europe’s crisis, International Socialism 109 (Winter 2006).

Kidron, Michael, 1970a, Western Capitalism Since the War (Pelican), the first section of this is currently available online.

Kidron, Michael, 1970b, The Wall Street Seizure, International Socialism 44, first series (July-August 1970).

Kidron, Michael, 1974, Capitalism and Theory (Pluto).

Kidron, Michael, 2002, Failing Growth and Rampant Costs: Two Ghosts in the Machine of Modern Capitalism, International Socialism 96 (Winter 2002).

Kliman, Andrew, 2007, Reclaiming Marx’s Capital: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency (Lexington).

Leiva, Orlando Capito, 2007, The World Economy and the US at the Beginning of the 21st Century, Latin American Perspectives, vol.134, no.1.

Marx, Karl, 1962, Capital, volume three (Moscow).

Marx, Karl, 1965, Capital, volume one (Moscow).

Marx, Karl, 1973, Grundrisse (Penguin).

Mastroianni, Kerry A. (ed.), 2006, The 2006 Bankruptcy Yearbook & Almanac, chapter 11 available from www.bankruptcydata.com/Ch11History.htm

Michl, Thomas R., 1988, Why Is the Rate of Profit Still Falling?, The Jerome Levy Economics Institute Working Paper number 7 (September 1988).

Mohun, Simon, 2006, Distributive Shares in the US Economy, 1964-2001, Cambridge Journal of Economics, volume 30, number 3.

Moseley, Fred, 1991, The Falling Rate of Profit in the Post War United States Economy (Macmillan).

Moseley, Fred, 1997, The Rate of Profit and the Future of Capitalism, May 1997.

Murray, Robin, 1973, CSE Bulletin, spring 1973.

OECD, 1996, Government Policies Towards Financial Markets, available from www.olis.oecd.org/olis/1996doc.nsf/

O’Hara, Phillip Anthony, 2006, A Chinese Social Structure of Accumulation for Capitalist Long-Wave Upswing?, Review of Radical Political Economics, volume 38, number 3.

Riley, Barry, 2007, Equities Run Short of Propellant, Financial News US, 16 Apr 2007.

Sheikh, Anwar and Ertugrul Ahmet Tonak, 1994, Measuring the Wealth of Nations (Cambridge University Press).

Steedman, Ian, 1985, Marx After Sraffa (Verso).

Stiglitz, Joseph, 2004, The Roaring Nineties: Why We’re Paying the Price for the Greediest Decade in History (Penguin).

Wolff, Edwin N., 2003, What’s Behind the Rise in Profitability in the US in the 1980s and 1990s?, Cambridge Journal of Economics, volume 27, number 4.

Last updated on 7 May 2021