MIA > Archive > P. Foot > Why you should be a socialist

‘In making itself the master of all the means of production, in order to use them in accordance with a social plan, society puts an end to the former subjection of men to their own means of production. It goes without saying that society cannot itself be free unless every individual is free. The old mode of production must therefore be revolutionised from top to bottom. Its place must be taken by an organisation of production in which, on the one hand, no individual can put on to other persons his share of the productive labour, this natural condition of human existence; and in which on the other hand productive labour, instead of being a means to the subjection of men, will become a means to their emancipation, by giving each individual the opportunity to develop and exercise all his faculties.’

Frederick Engels, Anti-Dühring

The capitalist disaster is all around us, clear to see. But for most people capitalism is ‘the best system we’ve got’. Before they destroy capitalism, they want to know – what can they put in its place? There is an alternative way of running society which is worth fighting for. It is called socialism.

Socialism is built on three principles, all vital to one another.

The first is the social ownership of the means of production.

Many people take this to mean the ownership of all property by some Big Brother state. They look around in their homes and see a few treasured possessions. Furniture, a television set, a washing machine, perhaps a car or some books. They do not see why they should give these things up to some bureaucratic state, or to anyone else for that matter.

Nor should they. And here is the first big misunderstanding, carefully nursed by the supporters of capitalism.

They deliberately ignore the obvious difference between people’s possessions and the means of producing these possessions.

If you own a washing machine, you do not get richer because you own it. On the contrary, you probably pay out large sums every month in hire purchase commitments. Even when you’ve finished buying it, there’s no extra income to you from having that washing machine. But if you own shares in Hoover, you grow richer because other people are buying washing machines.

The means of production are the factories, the machines, the chemical plants, the printing presses, the pits, the building materials - all the things which produce wealth. It is the ownership of all these by a small handful of people – or by a state which is run on behalf of that small handful of people – which leads to the inequalities and the chaos of capitalist society.

If the means of production are owned by society as a whole, then it becomes impossible for one group of people to grow rich from other people’s work.

It removes the compulsion for industries and services to compete with one another for the general wealth. It makes it possible to plan the resources of society according to their needs. The problem which dogs all businessmen: ‘who is going to buy back the goods’, and the slumps which that creates no longer arise. If, by mistake, too many goods are made or too many services are provided, then they can be given away or slowed down, and something else started. But there is no question of throwing millions of people out of work, or leaving machinery idle, or throwing food down mineshafts. These could not be possible, because the driving force of the production plan is human need.

Under socialism there is no stock exchange, no moneylenders, no property speculators, no landlords – no one getting rich out of someone else’s needs. All these are replaced by plans which are drawn up to meet the means of production with people’s needs.

The second principle of socialism is equality. The principle is ridiculed by rich men and their newspapers on the grounds that people are not the same. Of course people are not the same. They have different abilities, different likes and dislikes, different characters.

But equality is the opposite of sameness. Equality means that the rewards which people get out of society for what they do should not differ just because their abilities differ.

Two years ago, the Economist magazine estimated that if all the income in Britain were shared out evenly, every family would end up with £80 a week. He was trying to show how little difference income equality would make. Well, £80 a week per family at 1974 prices – more than £120 a week today – is enough to be getting on with.

Any socialist government would fix a firm maximum income and stop all rights of inheritance. But that is only a start. For socialism depends on the control of society through the social ownership of the means of production. And the shortest road to equality is to provide for everyone’s basic human needs free of charge. The services in today’s society which have been fought for and won by trade unionists and Labour supporters for a hundred years, and which are now being shattered, are sometimes known as ‘the social wage’. Under socialism, the ‘social wage’ takes on a new importance.

A free education service, founded on the principle that all children’s abilities are to be encouraged; a free public transport system; the absolute guarantee that old people will live in warmth, and light and comfort; a free health service and free housing for all – with security of tenure; free meals for children at school; free basic foods for every family; free day nurseries for all children – these basic needs of society become the top priorities of socialism.

As we’ve seen already, they are all possible even with existing resources. Under a new system of production which employs everyone and does not stutter from boom to slump, they can be made more readily available. And the more available they become, the more rapidly and enthusiastically society will produce for other, less obvious and more various human needs and desires.

The third pillar of socialism is workers’ democracy. Many people have a vision of socialism as a state bureaucracy, run by masses of officials, who stamp their prejudices and favouritisms on society with secret police forces and torture chambers. This caricature of socialism is played up by wealthy businessmen whose enterprises are run from top to bottom by unaccountable officials, stamping their prejudices and favouritisms on the people who do the work.

While the productive workforce declines, foremen and time study men proliferate. Every tightening of a screw, every visit to the toilet is timed and disciplined. Nor are workers safe when they leave the factory. Each corporation employs bands of security guards and experts, who not only keep guard on property but also check on the ‘affiliations’ of stewards and militants.

It is a central principle of socialism that the people who make decisions should be accountable to the people who are affected by them. Socialism and democracy, in other words, are indispensable to one another. You can’t have socialism without democracy, and, more importantly, you can’t have democracy without socialism.

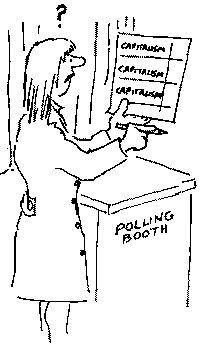

When people use the word ‘democracy’, they usually mean parliamentary democracy – a democracy limited to a vote at long, often irregular intervals: the sort of democracy which exists in Britain, France, Germany, Italy and America.

But this is an extremely limited democracy. It works on geographic lines – that is, people vote according to where they live. It operates only in a small corner of society. In the areas which matter – in industry, finance, the civil service, the law courts, the police force, the army, there is no democracy at all. Power is held by people because they have wealth or are part of a class which has wealth, and parliament does not challenge that power. The ‘mass of officials’ therefore, whether they work for multinational companies or the civil service or the law courts, are completely unaccountable. They operate, not on behalf of society, but on behalf of one class, and there is no democratic machinery to control them.

By contrast, the fundamental unit of workers’ democracy is the workers’ council. Because people come together and co-operate most at work, because production of wealth takes place at work, not at home – the workplace is a far better base unit for a democratic system than the home. The workers’ councils run through each part of industry and the services, but they do not operate as individual units competing with one another. They operate within the structure of an overall plan, drawn up by the government.

The government is also made up of workers’ representatives, elected through the councils, grouped this time on a regional basis, to a national Congress of Councils, which then elects its executive or government.

The workers’ councils form the core of socialist democracy, but they are not the only organs of democracy or of power. They co-operate and coexist with a whole number of other democratic organisations, such as tenants’ and consumers’ cooperatives. To be genuinely democratic their membership must be open to all working people who are not working – in particular to old workers or disabled workers or sick workers or workers who are caring for very young children.

The precise detail of these structures can’t and shouldn’t be laid down in advance. In all revolutions, or attempted revolutions, workers have found different patterns of workers’ councils and congresses.

But the basic principle is common to all revolutions – and vital. It is the accountability of the representative to the represented. Accountability means elections – far more elections than there are at present, and at many different levels. It means discussion and argument between different workers’ parties around those elections.

Accountability means paying representatives no more and no less than the average pay of the represented. It means subjecting the representative to the instant recall by the people, or council or cooperative, which elected them. Our parliamentary democracy ignores all these principles. MPs are always asking for more money, though most Labour MPs earn twice as much as the people they represent. They are not subject to instant recall.

The principle of elected controllers extends into every area of workers’ democracy. In the armed forces there are no appointed officers who are paid more than the people they order about. Instead, officers are elected and subject to control. In the law courts there are no unelected judges interpreting and laying down the law. The jury system, a profoundly democratic method of making decisions about justice, can be extended into the area of law interpretation and of laying down punishment. In hospitals and schools, top administrators are also elected and accountable. There, as elsewhere, the ‘mass of officials’ in every walk of life are strictly accountable to the elected bodies.

These are the broad guidelines of a workers’ democracy under socialism. What are the main objections to them?

|

The most common is that a socialist society founded on equality and, cooperation is ‘contrary to human nature’. ‘Human beings’ runs the argument, ‘are irrevocably greedy. They are irrevocably anxious to do damage to their fellows. So a system of society based on cooperation can’t possibly succeed. The only way to run society is to allow man’s bestial nature its full scope and hand over the running of society to stock exchange speculators and bankers in the City of London.’

The truth is that some people are all greedy, though only a few. Some are all unselfish, though only a few. Most people are greedy some of the time and unselfish some of the time.

Take a few examples from working class experience. James Cannon, the great American socialist, once wrote an article about a boilermaker who worked for the Consolidated Edison company, and who was badly burnt after an accident at work. James Cannon quoted from the New York Times:

‘Doctors who had treated Mr Sullivan said that his was the most extensive burns case they had ever seen recover. He was given three days to live when he entered Bellevue Hospital.

‘Fifteen skin graft operations were performed. Fourteen fellow workers from the Consolidated Edison, some who had not known Mr Sullivan before, gave two grafts each of 8 by 4 pieces of skin.’

James Cannon wrote:

‘This was the skin that made the difference. The skin of co-workers taken off their own bodies twice in 8 by 4 slabs for the benefit of another whom some of them at first didn’t even know. They merely knew that he was hurt and needed help, and they gave it.’

That sort of thing is going on all the time. In factory after factory, in a quiet, unpublicised way, workers are collecting money and giving up time for operations for the children of their mates or for a whole host of charities to assist the sick or the disabled. No rewards here; no advancement for their own children. Just spontaneous, regular sacrifice to help someone else.

Here’s two more contemporary examples.

In February 1976, Arthur Conheeney, an engineering union convenor who was leading a strike in a small factory in Warrington, Lancashire, was offered £16,000 pay-off by the management if he agreed to leave the factory. Arthur refused. The workers went on to win a strike for his reinstatement in the factory. Was that greedy? What about his human nature?

In May 1976, in Brentford, West London, a group of women came out on strike for equal pay. They stayed on strike for more than six months. They knew that even if they won the strike, it would take several years for them to make up in their increase the wages they lost while on strike. Yet they stayed on strike, and continued picketing, because they saw their effort affecting millions of other working women all over the country.

In thousands of disputes every year workers make astonishing sacrifices in strike action – often when they are not themselves affected.

There is nothing fixed or constant about human nature. There are plenty of examples from history to show that human beings are just as likely to respond to appeals for cooperation as to incentives from competition.

Intelligence tests to divide children on the grounds of their academic ability were only invented about 50 years ago. The psychologists who invented them went around the world trying them out on different races. They soon ran into unexpected difficulty with tribes of American Indians who had been brought up to think in a quite different way.

Among the Sioux Indians it was ‘regarded as incorrect to answer a question in the presence of others who did not know the answer’. The Hopi Indian children simply refused to answer the questions as asked. They replied to the psychologists: ‘Either we answer the question together – or we don’t answer it’. It was human nature to them that you didn’t shame or humiliate some people in the group through allowing others to prove himself or herself superior.

Who can say that those Indian children were any more ‘savage’ than their interrogators?

What’s good and what’s bad in human nature is decided by the kind of society people live in. If the main purpose of society is to make a fortune for a few, then the virtues which society extols will be the virtues of the fortune-makers – meanness, competition, ‘to hell with your neighbour’, ‘stuff your pockets never mind the other man’s’, ‘advance your children, abuse other people’s’, love your God, Queen and country, hate the people around you’.

If society is controlled by the people who work, in the interests of the people who work, then society will encourage another side of human nature: cooperation and concern for others, pooling of skills and resources, shop the ruffian and exploiter.

People are terrified of too much democracy, on the grounds that it will clog up the workings of a technological society. They see all around them hosts of ‘experts’, trained in science, sociology, economics. Surely, they ask, these people must be left to take the decisions?

Very few of us can understand a word they’re saying, and if we can’t understand how can we take part in decisions?

Such people suffer from an illusion. They imagine that the main decisions in our society are taken by experts. The main decisions are about the patterns of production. What should we produce and when? How much should we save? These decisions are not taken by experts. They are taken, in the main, by nincompoops, by people without any natural or technical talent whatever. Their only ability is the ability to bluff, bully or bribe their way to greater riches.

Roy Thomson, for instance, was a man of almost monumental mediocrity. He seldom read anything but a balance sheet. He had no technical knowledge or skill. Yet he became the king of a gigantic newspaper chain which spread right across North America. In Britain, Thomson owned and controlled The Times and Sunday Times. Brilliant men and women of letters, skilled printers, clever technologists all worked for Roy Thomson, but he took the decisions which mattered.

Howard Hughes was another mediocrity. He started life as playboy and ended it as a lunatic. He had no ability at all. Yet through a mixture of luck and the ability to read a balance sheet, Hughes became the boss of a gigantic financial and industrial empire. He was able, almost alone, to nominate the President of the United States, Richard Nixon, who also had no ability, knowledge or skill of any kind. Howard Hughes designed an aeroplane which crashed and directed a film which was a monumental failure. He couldn’t do anything which mattered. Yet he made the decisions. The list is endless. Successful capitalists, almost to a man, are not people with any natural ability. Yet they decide what the experts do. They decide that architects must construct Centre Point (the empty office block) or Ronan Point (a council block which fell down). They decide that engineers must build the Concordes. They decide that physicists must work on nuclear weapons.

Socialism removes these autocratic dunces from power and influence. Instead, the broad decisions – hospitals or offices, saving or spending, pensions or aid to India – are taken by democratically elected councils and congresses. All the evidence is that such bodies will take much wiser, saner decisions than the people who take them at present. And once the broad decisions are taken, the technical decisions about how to do them best will still be left to people with the necessary skill and knowledge.

All the thrust of socialist society will be towards the spreading of expertise and the enlargement of experts’ social responsibility.

Capitalist society isolates its experts from one another, and from society at large. It instils in them a jealousy of their expertise. Experts form themselves into closed groups – the Institute of Structural Engineers, the Law Society, the Parliamentary ‘lobby’ of political journalists. Then they defend their right to exclusive knowledge and practise in their field.

The more experts become isolated, the more anti-socially their expertise is applied. A recent Midweek programme on BBC showed a number of naval officers and scientists talking about the Polaris missile, which was fitted to the submarine on which they were working. They talked with astonishing frivolity about ‘letting off the big one’. Slaughtering millions, they explained, ‘was all in a day’s work’. They were ‘just obeying orders’. Some of these men were experts, extremely knowledgeable experts in one of the most developed sciences on earth: the science of destruction. Yet they talked about their weapons with the social responsibility of a hooligan.

Education in a socialist democracy would seek to ensure against the creation of experts in a single field. And socialist workers’ democracy would seek to involve all experts in the working out of industrial plans.

But wouldn’t there be a mass strike of all experts against an egalitarian society? Wouldn’t they all refuse to apply their knowledge unless they were paid more than the people who do the dirty work? What would be the incentive for an inventor or a scientist to come forward with new ideas, say, for labour-saving machinery unless he benefits from it?

The short answer is that he will benefit from it. Inventors and scientists do not discover things just because they will make a fortune from it. Some of the greatest inventions – penicillin, for instance – have been made by people who insisted on not making a personal fortune out of it. Scientists, experts of every kind get a benefit from applying their knowledge to the society, because that is what they like to do.

They prefer using their inventive skills to working as a labourer. In a society where everyone is expected to contribute, they would prefer to contribute in their own expert fields to any other form of contribution.

Thousands of experts would be liberated by a socialist society from the corruption of their skills which takes place under capitalism. In 1975, the workers at Lucas Aerospace, most of them highly-skilled, produced a document showing how the wealth in a highly-technological part of British industry could be switched from war production and wasteful motor car production to production which would meet people’s needs. Drawing on their technological and scientific knowledge, they showed how, even with the existing resources and existing labour, thousands of working people could start

to produce for the first time things of real benefit to their fellow men. The frustrations which provoked that document from the Lucas workers are always evident in every part of a society where expert, trained people are forced to suppress their wish to do something useful, and turn themselves instead to worthless and humiliating tasks which corrupt their abilities.

One last point about the ‘brain drain’ which capitalists always threaten us with in an egalitarian society. Capitalism is the biggest ‘brain drain’ of all, since it discounts the brains of about eighty per cent of the population.

Very few employers can do without a ‘suggestion box’ in which workers are asked to put in their ideas for reorganising the factory, or even for new machines.

Employers who are never prepared to concede a worker’s right to manage or to make decisions are only too happy to make use of ‘suggestions’, because they know, deep down, that the worker understands more about the workplace than anyone else. More often than not, workers can tell whether a new invention is going to work before it’s even tested on the public. Yet this vast fund of skill and knowledge is deliberately wasted to maintain class power. Socialism would open up the fund. The biggest brain drain of all would be staunched.

A third, familiar set of questions about socialism come from people who, quite naturally, dread the prospect of a society where people are treated like battery hens. Perhaps they have read Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, where test-tube babies are lined up in rows while a loudspeaker whispers ‘basic truths’ to them, or George Orwell’s 1984, in which all forms of affection are crushed out of human beings in order to subject them to ‘the system’.

These fears, as usual, are delicately stoked by the press and television of a capitalist society which is increasingly stamping sameness and conformity on its working people.

This propaganda always starts with ‘the home and the family’, which, it insists, socialists will abolish. All love between human beings and between parents and children will, they pretend, be ruthlessly ostracised by a socialist government.

The case for a socialist system starts from the freedom to enjoy and develop relationships – especially among children. Socialists argue that the greatest enemy to that freedom is the drudgery of work – both work at the point of production and work in the home. The provision of labour-saving machinery inside the factory and of communal facilities outside – nurseries, cheap restaurants, laundries, ironing services: all these increase the freedom of people to expand and enjoy their individual lives and relationships. Socialism does not ‘abolish the family’ by decree, or make it illegal or impossible for men and women to live in pairs with their children. Quite the opposite.

By providing collective facilities to lessen the drudgery of life at work and at home, socialism sets out to give people the time and the leisure to enjoy one another. One of the effects is to cut down people’s dependence on the family.

Under capitalism, hundreds of thousands of men, women and children cling to family relationships long after they have grown sour or even savage. They do so, chiefly, because the family offers them economic security, while outside the family there is no security at all. Socialism sets out to provide security for all human beings whether they live in families or not. It enriches the relationships inside families and liberates countless thousands from forced and tortuous relationships.

And so we come back to the central charge against socialism: the charge of the ‘battery hen society’.

Capitalism promotes such a society. Capitalism promotes inequality and sameness. Capitalists proclaim that only a few are entitled to wealth and leisure, and therefore only a few have the time to read books or look at pictures or go to the theatre or enjoy great musical works or understand the marvels of science. Capitalists insist that the majority are condemned to eternal sameness; that they are illiterate, stupid, insensitive, brutish, preferably obsequious but always the same. Inequality and sameness are part of the same creed, and both are central to capitalist society.

The supporters of capitalism always pretend to be supporters of liberty and freedom. They describe the profit system as ‘free enterprise’ and pretend that ‘free enterprise’ is bound up with the freedom of the individual. They say that we live in a ‘free country’.

If you ask these people what they mean by freedom they stress things like ‘freedom to choose your child’s education’. What they mean by that is freedom to have your child privately educated for a fee. But that freedom is open only to a tiny minority of people who can afford school fees in the first place. For the vast majority, the freedom to pay for their children’s education is no freedom at all. Because they can’t afford to pay the fees. Everyone is ‘free’ to have tea in the Ritz. But only a tiny handful can afford £5 for a cup of tea and a bit of toast. So the ‘freedom’ is the freedom of a tiny minority.

That’s what capitalists and their supporters mean by freedom: freedom for the minority with the wealth. That freedom is the exact opposite of freedom for the majority. The more freedom you allow to wealthy people to use and expand their wealth, the less freedom there is

for the people without wealth. Freedom is quite meaningless if you have no money and no time to make use of it. That’s why the French revolution raised the slogans Liberty and Equality together. You can’t have liberty without equality, and you can’t have equality without liberty. The two are part of the same idea. Socialism is about equality, liberty and individuality.

The three are closely bound to each other. The chief argument for equality is that it releases the mass from the bonds of exploitation, makes possible the development of the resources of society in such a way as to relieve drudgery and boring work, and so allows all human beings to expand their individual potential.

There is then no limit to the individual aspirations of every man and woman. A hundred and sixty years ago, the great revolutionary poet Shelley caught a glimpse of it in his poem, Queen Mab:

|

How many a rustic Milton has passed by, |

A hundred years later, after the Russian revolution, the revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky wrote of the same vision:

‘Lastly, in the deepest and dimmest recesses of the unconscious, there lurks the nature of man himself. On it, clearly, he will concentrate the supreme effort of his mind and of his creative initiative. Mankind will not have ceased to crawl before God, Tsar and Capital only in order to surrender meekly to dark laws of heredity and blind sexual selection. Man will strive to control his own feelings, to raise his instincts to the height of his conscious mind, and to bring clarity into them, to channel his willpower into his unconscious depths; and in this way he will lift himself to new eminence.’

In between those hundred years, and countless times since, socialists have dreamt like Shelley and Trotsky dreamt, and have fought the harder for it.

But socialists are not Utopians. They do not believe that socialism is like the ‘Big Rock Candy Mountain’ in the children’s song, where the ‘rain don’t rain and the wind don’t blow’, and where ‘they hung the jerk that invented work’.

Socialism is about human beings, and human beings make mistakes. There will be plenty of mistakes made by a workers’ democracy, plenty of wrong decisions taken, plenty of cases where the wrong things are made at the wrong time and distributed to the wrong place.

No one can guarantee against jealousy or ineptness or pain. Socialism provides only the structure in which men and women can cooperate to put their mistakes right; to curb their jealousies in the common interest and to relieve pain wherever it emerges.

By the same token, the precise details of a socialist society cannot be laid down in advance. The case for socialism is not built on precise guidelines, all clearly marked out – with the guarantees against mistakes and bureaucracy written into a constitution. We’re describing a society to be brought about by the efforts of the common people, so we cannot be exact at a time when those efforts have not been made. Our description is limited by the narrowness of the society in which the masses still remain passive.

But we can describe the broad outlines, the necessity for public ownership, for equality, for a workers’ democracy.

And we can say with absolute certainty that the alternative is barbarism. The extent of that barbarism is shouted out from torture chambers all the way from Santiago to Robben Island, South Africa. In the age of the atom bomb and germ warfare, the barbarism of a desperate capitalism knows no bounds.

The ‘devil we know’ is getting more and more vicious every minute. If we hang around too long worrying about his replacement, he will devour us all.

There is a story about an Indian guru who came to the house of a fastidious peasant. The guru knocked on the door. ‘Excuse me,’ he muttered politely, ‘but your house is on fire.’

The door was not opened. The peasant grumbled: ‘Is it raining outside?’

‘Well, yes it is,’ said the guru. ‘It is very wet. But you must come out here right away, or else I assure you, you will be burnt to death.’

‘But where am I to spend the night?’ insisted the peasant. ‘I have a bed here, but I’ll bet there isn’t anyone in the village who’ll take me in.’

‘Maybe not,’ shouted the guru angrily. ‘But you’ll be better off sleeping in the rain than you will be in your house.’

‘Do you realise I built this house with my own hands?’ shouted the peasant equally angry. ‘Everything I have is here; a table, a bed, some books, some cooking utensils. Where is the table and bed and cooking utensils outside, I’d like to know?’

‘Very well,’ said the guru, and he walked away.

The house burnt down and the peasant with it.

Last updated on 7.1.2005